Market Valuation

-

Reporting Season – Emerging Conclusions

Tim Kelley

August 30, 2012

Reporting season is a busy time for us at Montgomery Investment Management. Studying results announcements is one of the ways we try keep on top of what is happening in the market and identify economic trends and investment opportunities.

We do this in a fairly systematic way. Every day we review, evaluate and catalogue every last results announcement made that day. As I write, we have reviewed several hundred sets of financial statements and the accompanying commentary, representing around $700B of aggregate market capitalisation, with many more still to come.

This analysis draws our attention to individual companies that are performing well, and complements the automated stock screening tools we use, including Skaffold. It also gives us a sense of broader economic trends and the relative health of different parts of the economy.

by Tim Kelley Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Market Valuation.

-

Australian Bank results show 1 Speed Aussie economy – SLOW

Roger Montgomery

August 20, 2012

The full year result by CBA recently was a good reflection of the level of growth Australia is currently experiencing – low. The banks reported cash NPAT was up just 4% for the full 12 months or $278m to $7.1b. However, if we back out the 15% reduction in loan impairment expenses, $191m, despite the oligopoly the big 4 have in Australia, the best they could manage was growth overall of 1-2% in banking, funds management and insurance. The 15% improvement in credit quality was definitely a surprise in the result given the scores of jobs losses recently. A development we continue to monitor closely.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Market Valuation.

- 1 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Market Valuation

-

Reporting Season Update

Roger Montgomery

August 18, 2012

Over the past week more than 100 companies have reported their full year results. These results have begun to flow through Skaffold, resulting in the changes listed below for each company. A membership to Skaffold ensures you are constantly up to date with changes to the quality and valuations of every Australian listed company.

To become a Skaffold member and start taking advantage of market inefficiencies that may transpire during reporting season CLICK HERE

And here’s a list of the elements in Skaffold that change automatically as companies report:

1. Earnings and Dividends, Capital History and Cash Flow Evaluate screens updated with 2012 figures

2. New 2012 Skaffold Score

3. 2012 Intrinsic Value – Actual

4. 2013, 2014 and 2015 Intrinsic Value forecasts

continue…by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Investing Education, Market Valuation, Skaffold.

-

Materials stocks will be doing it tough. More bad news from offshore…

Roger Montgomery

August 16, 2012

At its Annual General Meeting held in Mumbai yesterday, the Chairman of Tata Steel, Ratan Tata, reported an 89% plunge in its June Quarter 2012 net profit. <http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tata-steel-ltd/stocks/companyid-12902.cms>

Mr Tata said the Company will need to restructure its operations due to a slackening of global steel demand. From their 2006 acquisition of Corus, around half of Tata Steel’s 24 million tonnes per annum capacity is European based.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong listed China Resource Cement has released a disappointing interim report to June 2012. Accordingly, their net profit forecast for each of 2012, 2013 and 2014 has been cut aggressively. Despite building capacity by 25% to 64 million tonnes of cement per annum, the gross profit margin per tonne for 2012 is expected to be less than half that recorded in 2011. China Resource Cement’s net profit should be around HK$1.4 billion in 2012, down 67% from HK$4.2 billion in 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Market Valuation.

- 1 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Market Valuation

-

You wouldn’t believe it…

Roger Montgomery

August 9, 2012

Many believe that understanding economics is the key to being able to predict the stock market. Curiously the Chinese economy is growing the fastest of all economies and is variously described as the global growth engine. And the Chinese ripples positively impact many peripheral economies too, as my recent visits to Singapore have shown me.

Many believe that understanding economics is the key to being able to predict the stock market. Curiously the Chinese economy is growing the fastest of all economies and is variously described as the global growth engine. And the Chinese ripples positively impact many peripheral economies too, as my recent visits to Singapore have shown me.Meanwhile the US economy is in the doldrums, threatening to fall into another recession with anemic growth, stubbornly high unemployment and continued weakness in housing.

And yet the Chinese market as measured by the Shanghai Stock Exchange A Share index remains 65% below its high of 6391.98 in October 2007. Perhaps ironically the S&P500 made its high of $1565.42 on October 10, 2007 and today it sits just 11% below that. If the Total Return index is taken into account, its sits level or just above its 2007 highs.

So all that chatter about recessions, depressions, unemployment and the like counts for very little. How many children are suffering needlessly because the money spent on economists isn’t directed to the kids?

What we do know is that investors should be looking at individual companies. Or talking to people on the ground. In China, balance sheets are deteriorating as receivables blow out while in the US, of the 411 companies listed on the S&P 500 that have reported earnings so far this quarter, 297 have exceeded analysts’ estimates, while less than 110 have missed their forecasts. And as many of our travelling clients have informed us, things seem to be swimming along in the US.

Keep an eye on individual companies and you’ll go far. So don’t worry about whether you should say Go Australia or not. We say Go ARB, Go WOW, Go CCP, Go COH and Go CSL!

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Market Valuation.

-

Credit Corp’s results announcement

Roger Montgomery

August 7, 2012

Credit Corp (ASX:CCP) has just reported their FY12 results, announcing a NPAT of $26.6m versus market forecasts and company guidance of $25-28m.

The company increased its 2H12 dividend to 16 cps and most analysts were expecting 15 cps forecast. The 16 cent dividend takes the full year dividend to 29 cents, which is 45% higher on the previous year. The company has talked down the forthcoming year and cited increasing competition resulting in higher ledger purchases. Investors need to accept this at face value rather than continuing to assume the company will upgrade again at the next half year (as they have done consistently in the past). FY13 guidance for NPAT is $27-29m and DPS of 29-32 cps. Based on an estimated 50% payout and an estimated 22% ROE our valuation is further estimated (estimated being the operative word here) to remain well above the current price. The comments here are for educational purposes only and not a recommendation. Be sure to seek and take personal financial advice prior to engaging in any securities transactions.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Intrinsic Value, Investing Education, Market Valuation.

-

Reporting Season – it won’t be much of a celebration!

Roger Montgomery

August 3, 2012

Over the next 20 business days, approximately 1,250 ASX listed companies will be reporting their full year (or interim) results to 30 June, 2012.

Twelve months ago, the consensus forecast for the year to 30 June 2012, was for 20% growth in earnings per share.

Over the past twelve months that number has been progressively downgraded to nil, nought, nothing.

For the year to 30 June 2013, the consensus forecast currently stands at 15% growth in earnings per share.

Insights from the outlook statements will be interesting and it wouldn’t surprise us to see consensus earnings per share growth forecasts for the year to June 2013 to follow the same downtrend as those for the year to June 2012.

At Montgomery, we will be using our proprietary fact-based investment process to analyse the results.

We hope this reporting season will alert us to some new companies which own extraordinary businesses trading at a discount to their estimated intrinsic value.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Market Valuation.

-

MEDIA

Have we finally reached the bottom of the market?

Roger Montgomery

July 30, 2012

And what are Roger Montgomery’s Value.able Insights into the latest market developments? Learn more in this edition of ABC1’s “Inside Business” broadcast 29 July 2012. Read/Watch here.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Energy / Resources, Intrinsic Value, Market Valuation, Takeovers, TV Appearances.

-

Is this the fate that awaits Australian Iron Ore Producers?

Roger Montgomery

July 26, 2012

Could it get any worse for Iron Ore? It Just did!

Could it get any worse for Iron Ore? It Just did!News Flash! Shipping more iron ore volumes at lower prices is the same as JBH and HVN selling more TV’s a lower prices. Margins compress and profits don’t meet expectations.

Back in April, when we began more urgently warning investors to look carefully at profit assumptions for the big material stocks, our theory was that iron ore prices would decline because of a massive supply response. It really was basic supply and demand. Economics 101. You can read our warning here: http://rogermontgomery.com/is-the-bubble-bursting/

Back on December 8 2011, with BHP trading at more than $37.00 we again warned:

“I now wonder whether we are seeing the bubble slip over the precipice? Falling property prices (10 per cent of the Chinese economy) leads to lower construction activity, leads to declining demand for Australian commodities, leads to falling commodity prices, leads to big drops in margins for a sizeable portion of the [Australian stock] market index…”

The doubters and many analysts that cover the sector however told us that lower prices would just mean that BHP, RIO and FMG would simply ship more volume. Remember share price performance over the long run follows profitability not profit.

And here’s the latest…

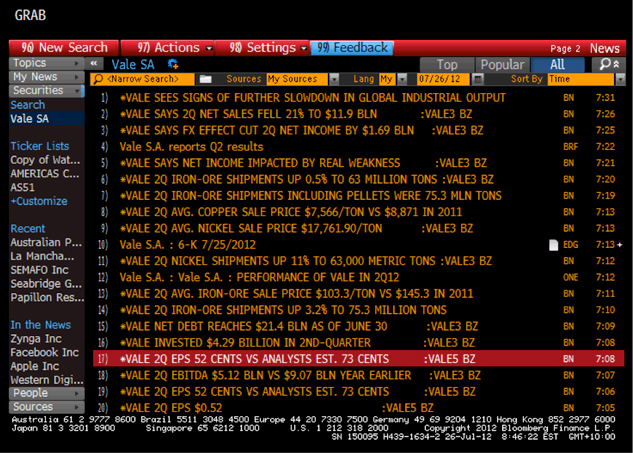

According to a news article that landed in the Bloomberg terminal this morning (see screenshot), Rio de Janeiro-based Vale, the world’s largest iron- ore producer, said second-quarter profit plummeted 59 per cent after prices for iron ore, nickel and copper declined.

Net income dropped to $2.66 billion, or 52 cents per share, from $6.45 billion, or $1.22 per share a year earlier. Vale was expected to post per-share earnings of 73 cents. The selling price of iron ore and most of Vale’s main products is lower than in 2011. This explains the decline in earnings.

Net sales fell 21 percent to $11.9 billion despite an increase in supply / production at Carajas, its biggest mine. Vale reportedly sold its iron ore at an average $103.29 per metric ton, down from $145.30 last year – something we have been warning for 6 months may happen. Nickel’s average sales price dropped 31 percent and copper declined 15 percent.

The stock has fallen 24 percent in the past 12 months, twice the 12 percent decrease in Brazil’s benchmark Bovespa Index. Management has put the focus of the fall squarely on slowing economic growth in China, the world’s biggest steel producer.

Returning to BHP, just 12 months ago, analysts had forecast 2012 net profits of almost $22b rising to $23b in 2013.

Those forecasts now stand at $17b and $18b respectively, representing a massive 22%-23% downgrade. And like Vale, BHP has also materially underperformed the ASX 200 index.

And given the significant miss by Vale analysts this morning, we reckon forecast earnings for BHP, RIO, FMG, MIN, AGO, BCI might disappoint again in the near future.

The answer in future periods may in fact lie in the Shanghai Re-bar prices and we have been watching this closely. Why? Because this is the most-traded steel futures contract and last week it hit a 2012 low.

Are iron ore prices, currently trading around China’s cost of production of $120/t, about to follow Re-bar prices despite most predicting the price simply cannot fall past this point?

The last time Re-bar prices were at this level, iron ore prices were also significantly lower.

When I was last on the ABC’s Inside Business program (watch it here: http://rogermontgomery.com/an-important-announcement/), we discussed Fortescue Metals CFO stating that their long-term iron ore price target is $100/t. I wonder how long we will have to wait until that forecast is also revised lower? As always, time will tell. Vale’s news is not a good omen.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Energy / Resources, Market Valuation.

- save this article

- POSTED IN Energy / Resources, Market Valuation

-

Is this yet-more evidence of the China slow-down?

Roger Montgomery

July 20, 2012

I thought the downgrade in earnings by a major stockbroker of the Chinese cement stocks by 20-30% for the years to December 2012 and 2013 was revealing. Anhui Conch, for example, one of China’s largest cement producers, is expecting its sales volume to grow by 17 percent per annum from 158 million tonnes in 2011 to 251 million tonnes in 2014. While the average selling price per tonne for 2012 is down 15% to 20% on 2011, and the gross margin has halved. This drives home the cyclical nature of the industry and in the past year the Anhui Conch stock price has also halved to HK$20.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Investing Education, Market Valuation.