With school holidays well and truly underway, plenty of my peers are also taking a few days off here and there to take their kids to the football finals, duck up to the beach or entertain. That offers plenty of time to review your portfolio with recurring profits in mind.

With school holidays well and truly underway, plenty of my peers are also taking a few days off here and there to take their kids to the football finals, duck up to the beach or entertain. That offers plenty of time to review your portfolio with recurring profits in mind.

Stability and predictability are two key words that many investors are unlikely to have heard in recent times and two important components of the ‘toolkit’ that may have gone astray. But at all junctures of the business cycle, stability and predictability are helpful investment partners.

Irrespective of whether you are building a portfolio from the ground up or are reviewing your current holdings, it is vital that you ensure your portfolio is always pointed in the right direction. Few, if any are able to reliably and predictability predict short-term share prices so there is relevance, if not necessity, in ensuring the very best opportunity is given to your portfolio. When a recovery transpires and investors are willing to accept risk again, the portfolio constructed from businesses with some stability and predictability to their revenues and earnings streams will have an excellent chance of outperformance.

While there are many definitions of what constitutes ‘stable’ and ‘predictable’, in terms of business analysis, recurring revenue would be the one I would use. And if you built a portfolio of such businesses, would it matter if this week a country defaulted on its debt or another had its credit rating downgraded? These issues are both temporary in nature and only likely to impact share prices, not the economics of the business.

Long-term contracts are the best form of recurring revenues and these contracts take many forms; There are of course the obvious long-term contracts, such as a mobile phone plan, internet or TV subscription, a car lease or a property tenancy, but less obvious are the long-term contracts we have with our own bodies to feed them, clean them and take out the waste. We have a long-term contract with our teeth, our cutlery and our toilets and these contracts ensure Coles and Woolworths, Kelloggs, Procter & Gamble and Kimberley Clark have millions of customers buying their consumables frequently and with monotonous regularity. In other words – recurring revenue.

Knowing that a percentage of revenue can be relied upon to come in the door each year allows a business to budget, rewarded staff consistently and plan expansions with fewer surprises.

And if you are buying a small piece of such a business, you can sleep more comfortably at night ‘knowing’ that your share will always have value even if the share price halves or worse.

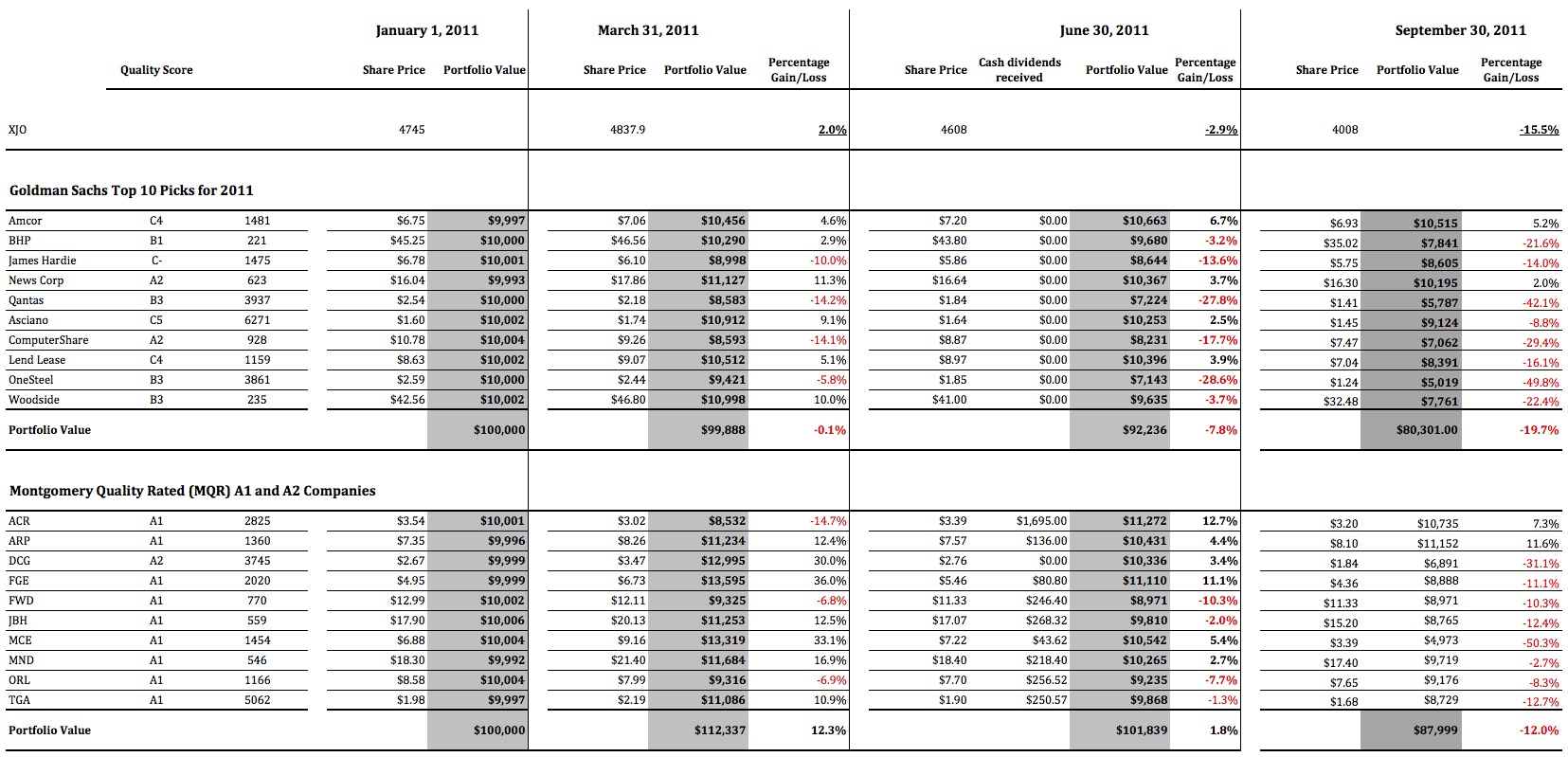

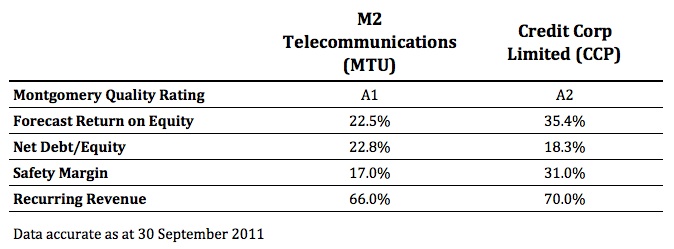

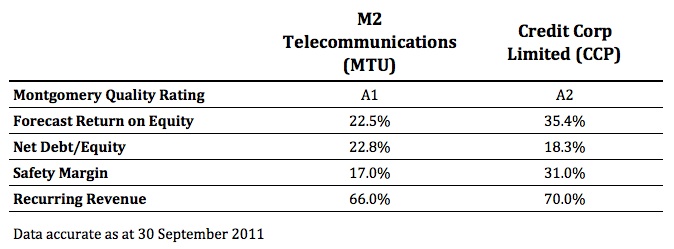

The following two businesses are examples of companies we hold in The Montgomery [Private] Fund, and that we believe display the characteristic discussed.

M2 Telecommunications is a reseller of telecommunications equipment and services into the $6 billion SMB Telecommunications market. While dominated by Telstra (ASX:TLS) with 80 per cent market share, M2 is the seventh largest Telco in Australia with a 4.5 per cent share.

Two thirds of the business’s revenue is recurring via traditional fixed voice services, mobile (phone and broadband) and wholesaling services. Typically, contracted revenue is on 2-4 year terms giving management a significant amount of predictability.

It is due to this predictability that management have forecast 15 per cent earnings growth for FY12 and have the ability to self-fund a couple of large acquisitions, which Vaughn Bowen has moved aside from day-to-day duties to focus on.

Credit Corp – With new management installed and a demonstrated focus on transparency and sustainable growth, 70 per cent of collections are now on recurring payment arrangements.

This frees up collection staff to focus on those clients that are finding it harder to repay their liabilities and drives efficiencies across the group. Not only this, but the degree of certainty has allowed management to invest in even more self-funded ledger purchases and forecast earnings of $21m-$23m in FY12.

Additionally, the businesses offer the following financial metrics:

High Montgomery Quality Ratings (MQR), high forecast ROE’s, low debt levels, a Safety margin and high, recurring revenues have attracted us. After conducting your own research and seeking and taking personal professional advice, I’d be interested to know whether these companies or any others meet your recurring revenue test.

Go ahead and use this blog post as the beginning of a thread listing companies with solid recurring revenue and earnings.

Given the time to be interested in stocks is when no one else is, now is the time to go through your portfolio and determine those holdings that have a component of revenues that are recurring.

Posted by Roger Montgomery and his A1 team, fund managers and creators of the next-generation A1 stock market service, 30 September 2011.