Technology & Telecommunications

-

The post-PC revolution

Roger Montgomery

April 17, 2013

At Montgomery we have several investment themes that influence our enthusiasm for an investment that meets all our other criteria.

continue…by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Technology & Telecommunications, Value.able.

-

Does intellectual property have the value it once had?

Tim Kelley

April 10, 2013

A strong competitive “moat” is one of the features we value in a business. Moats can take many different forms, but one appealing type of moat is that provided by intellectual property, ideally protected by patents.

Companies like Cochlear, Resmed and Codan are good examples of businesses that owe part of their prosperity to technology that provides an edge over competitors. In many cases, this edge has been built and maintained over many years through substantial investments in R&D.

continue…by Tim Kelley Posted in Consumer discretionary, Insightful Insights, Technology & Telecommunications.

-

Telstra’s Growth Conundrum

Tim Kelley

March 27, 2013

Today’s AFR reports on Telstra’s (TLS) capital investment plans, and states that the man in charge of those investment plans, Brendon Riley, believes that “the answer to the growth question is to keep investing.”

We don’t disagree with this in principal, but note that historically, TLS has not had much success in investing for growth. continue…

by Tim Kelley Posted in Insightful Insights, Technology & Telecommunications.

-

MEDIA

Mining Services – a looming train wreck…

Roger Montgomery

March 27, 2013

In this interview on ABC1’s ‘The Business’, Roger discusses with Ticky Fullerton why he is virtually certain that the Mining Services industry is facing disaster, and he also is highly sceptical about Telstra’s (TLS) prospects. Watch here.

This program was broadcast 27 March 2013.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Energy / Resources, Technology & Telecommunications, TV Appearances.

-

Telstra (TLS) vs M2 Telecommunications (MTU)

David Buckland

March 27, 2013

Interviewed by Peter Switzer last Thursday, I was asked why Montgomery doesn’t own any Telstra (ASX: TLS) shares.

Montgomery is a value investor that uses a highly disciplined and fact-based investment process.

We focus on investing in “extraordinary businesses” trading at a discount to their estimated intrinsic value.

by David Buckland Posted in Insightful Insights, Intrinsic Value, Technology & Telecommunications.

-

What is a game changer?

Roger Montgomery

March 20, 2013

Last night I received an unsolicited text message from Vodafone informing that Samsung had just released their Galaxy 4S. Vodafone cooed “it looks like a game changer”. Last week it was Dominos Pizza who insisted that new toppings (toppings others already had) and a square base (competitors already have those too) were ‘game changers’.

The noun Game Changer is being used a little too liberally at the moment, and lest it creep into our vernacular to such a degree that university students use it to describe skipping the train and catching the bus instead, I thought I’d attempt to use photographs to illustrate my understanding of game changers:-

continue…by Roger Montgomery Posted in Consumer discretionary, Insightful Insights, Technology & Telecommunications.

-

MEDIA

The numbers game

Roger Montgomery

March 1, 2013

In his March 2013 Money magazine column, Roger provides his insights into how to determine the true value of a business. Read here.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in In the Press, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Technology & Telecommunications.

-

Cisco: Mobile data traffic to grow at 66% p.a. over the next five years

David Buckland

February 18, 2013

The Cisco White Paper, released recently, makes some extraordinary predictions over the next five years and and is well worth reading.

To summarise:

1. In 2012, global mobile traffic grew 70 per cent to 885 petabytes per month. By 2017, this will grow 13 times and surpass 11 exabytes per month, a compound annual growth rate of 66%;

by David Buckland Posted in Insightful Insights, Technology & Telecommunications, Value.able.

-

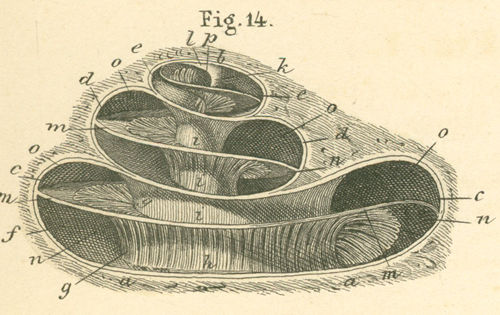

Cochlear? A second bite of the cherry for investors?

Roger Montgomery

February 11, 2013

Cochlear will be familiar to all of you. The company manufactures an implant that provides the gift of hearing to many thousands of hearing impaired people around the world. As you are also now aware Cochlear voluntarily recalled its Nuclear CI500 series in September 2011. Cochlear immediately switched to distributing its previous Nucleus CI24RE model with the new processors. And finally, you would be aware that Montgomery believed the recall was a rare buying opportunity buying as many shares as our portfolio construction process would allow at $50.

continue…by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Technology & Telecommunications.

-

MEDIA

Telstra: Price Up, Value Way Down

Roger Montgomery

February 7, 2013

In these highlights from The 7 February edition of the Switzer Report, Roger addresses in detail the causes for the rising Telstra share price, and how the underlying position of the company is being impacted.

Roger also discusses The Reject Shop (TRS), Kathmandu (KMD), CSL (CSL), Seek (SEK), REA Group (REA), Resmed (RMD), and Leightons (LEI) – do they achieve the coveted A1 grade? Watch now to find out. Watch here.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Technology & Telecommunications, TV Appearances.