Investing Education

-

What is your WOW Value.able valuation now Roger?

Roger Montgomery

February 14, 2011

With food prices on the way up and Woolies share price on the way down, I have received many requests for my updated valuation (my historical $26 valuation was released last year). Add to that Woolworths market announcement on 24 January 2011, and you will understand why I have taken slightly longer than usual to publish your blog comments.

With food prices on the way up and Woolies share price on the way down, I have received many requests for my updated valuation (my historical $26 valuation was released last year). Add to that Woolworths market announcement on 24 January 2011, and you will understand why I have taken slightly longer than usual to publish your blog comments.With Woolworths’ shares trading at the same level as four years ago (and having declined recently), I wonder whether your requests for a Montgomery Value.able valuation is the result of the many other analysts publishing much higher valuations than mine?

Given WOW’s share price has slipped towards my Value.able intrinsic value of circa $26, understandably many investors feel uncomfortable with other higher valuations (in some cases more than $10 higher),

Without knowing which valuation model other analysts use, I cannot offer any reasons for the large disparity. What I can tell you is that no one else uses the intrinsic valuation formula that I use.

So to further your training, and welcome more students to the Value.able Graduate class of 2011, I would like to share with you my most recent Value.able intrinsic valuation for WOW. Use my valuation as a benchmark to check your own work.

Based on management’s 24 January announcement, WOW shareholders can expect:

– Forecast NPAT growth for 2011 to be in the range of 5% to 8%

– EPS growth for 2011 to be in the range of 6% to 9%The downgraded forecasts are based on more thrifty consumers, increasing interest rates, the rising Australian dollar and incurring costs not covered by insurance, associated with the NZ earthquakes and Australian floods, cyclones and bush fires. The reason for the greater increase in EPS for 2011 than reported NPAT is due to the $700m buyback, which I also discussed last year.

Based on these assumptions and noting that WOW reported a Net Profit after Tax of $2,028.89m in 2010, NPAT for 2011 is likely to be in the range of $2,130.33 to $2,191.20. Also, based on the latest Appendix 3b (which takes into account the buyback), shares on issue are 1212.89m, down from 1231.14m from the full year.

If I use my preferred discount rate (Required Return) for Woolies of 10% (it has always deserved a low discount rate), I get a forecast 2011 valuation for Woolworths of $23.69, post the downgrade. This is $2.31 lower than my previous Value.able valuation of $26.

If I am slightly more bullish on my forecasts, I get a MAXIMUM valuation for WOW of $26.73, using the same 10% discount rate.

So there you have it. Using the method I set out in Value.able, my intrinsic valuation for WOW is $23.69 to a MAXIMUM $26.73.

Of course, I only get excited when a significant discount exists to the lower end of these valuations and until such a time, I will be sitting in cash.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 14 February 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

How has my Switzer Christmas Stocking Selection performed?

Roger Montgomery

February 10, 2011

On the last show of 2010, Peter Switzer asked me to list six of my A1 businesses that, at the time, were displaying the largest margins of safety. Tonight Peter has invited me to join him once again to review how those six A1s have performed (and chat about Telstra’s result no doubt). Tune into the Sky Business Channel (602) from 7pm (Sydney time).

On the last show of 2010, Peter Switzer asked me to list six of my A1 businesses that, at the time, were displaying the largest margins of safety. Tonight Peter has invited me to join him once again to review how those six A1s have performed (and chat about Telstra’s result no doubt). Tune into the Sky Business Channel (602) from 7pm (Sydney time).Here’s the article/transcript from that appearance.

Click here to watch the latest interview and discover how my A1 picks performed.

A1 stocks are the cream of the crop, but how do you know which stocks measure up? To find out, Roger Montgomery joins Peter Switzer on his Sky News Business Channel program – SWITZER.

Montgomery explains he classes companies from A1 down to C5.

“A1 is a business, I think, that has the absolute lowest probability of what I call a liquidity event – the lowest chance of having to raise capital, the lowest chance of needing to borrow more money, the lowest chance of defaulting on any debt that it has, breaching a banking covenant or a debt covenant, the lowest chance of needing money or going bust,” he says.

Montgomery says he’s interested in consistency of performance – A1s that he think will be A1 in the next 12 months.

“I’m looking for the companies that have been consistently A1s or A2s over a longer period of time,” he says. “They’re the ones that I think are most likely to be next year as well.”

Montgomery stresses that it’s important to diversify and get professional advice.

“Make sure you don’t bet the farm on any one company,” he says. “That’s why you need personal professional advice, because you’ve got to make sure that you’re doing the right thing for you and everybody has different risk tolerances.”

Montgomery’s A1 stocks

Platinum Asset Management – he says this is an “obvious A1 – a great performer, has no need for debt, pays all of its cash out.” The company is trading at about its intrinsic value, so it’s not a bargain, but it’s good quality. The intrinsic value is expected to rise around 14 per cent over three years.

Cochlear – “It’s been an A1 for years,” he says adding that its current share price is not cheap enough. Its intrinsic value is expected to rise around 13 per cent over the next three years.

Blackmores – “Expensive at the moment,” he says. “The intrinsic value is only expected to rise about five per cent over the next three years.”

Real Estate.com – “It’s expensive again – it’s trading at about 15 per cent above its intrinsic value.” The intrinsic value is expected to rise 15 per cent in a year. Its intrinsic value is forecast to rise by about 15 per cent a year. “In a year’s time, its intrinsic value will be its current price.”

M2 Telecommunications – This company is trading at a 10 per cent premium to its intrinsic value, Montgomery says. “It’s not cheap, but its intrinsic value is forecast to rise by eleven and a half per cent.”

Mineral Resources – This is a mining services business and is trading around its intrinsic value. The intrinsic values are forecast to increase by around 30 per cent a year over the next three years – “So that’s not bad.”

DWS Advanced – Montgomery says this IT services business is trading at a three per cent discount to intrinsic value and its intrinsic value is expected to rise by about 13 per cent.

Centrebet – Montgomery explains that people tell him there’s not many competitive advantages with the company because barriers to entry to the industry are low. “The owners of the licenses for these things would say they disagree – barriers to entry are quite high,” he says. Centrebet is at a six per cent discount to intrinsic value and it’s forecast to rise around five per cent a year, Montgomery says.

ARB – “Trading at about 11 per cent discount to its intrinsic value. Forecast intrinsic value is going to rise by about three-and-a-half per cent,” he says.

Oroton – “There’s been some talk about the CEO selling shares. The issue is I’ve bought shares from CEOs and founders who’ve sold shares and the share price has gone up a lot since then. I’ve also seen situations where the CEO has sold and that’s been the best time to have sold.”

Montgomery says there hasn’t been research to show CEOs selling shares indicated anything, but there has been research to suggest CEOs buying shares may indicate something. Oroton is trading at a 13 per cent discount to intrinsic value and is expected to rise 13 per cent per annum.

Companies trading at premiums to their intrinsic value

Reckon

Thorn Group

GUD Holdings

Fleetwood

Wotif

Monadelphous

The intrinsic value on these companies are rising anywhere from six per cent to around 17 per cent per year over the next three years, Montgomery says.

Montgomery says it’s important to do further research on the companies – “you can’t just go out and buy them – some of them, as I’ve pointed out, are expensive, so I wouldn’t be buying them. Some of them are A1s but that doesn’t mean that they’re amazing businesses and they’re the best businesses to buy. They’re the least chance of having a liquidity event.”

Companies trading at discount to intrinsic value

Montgomery explains he isn’t predicting share price; he’s valuing the company.

“Valuing a company is different to predicting where the share price is going to go”.

In descending order – biggest discount to smallest discount:

Matrix

Composite and Engineering

Nick Scali

JB Hi-Fi

Oroton

ARB

Centrebet

DWS

“We’ll come back in the New Year, we’ll have a look at how the index has gone, and we’ll have a look at how that little group of companies has performed.”

Important information: This content has been prepared by www.switzer.com.au without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. For this reason, any individual should, before acting, consider the appropriateness of the information, having regard to the individual’s objectives, financial situation and needs and, if necessary, seek and take appropriate professional advice.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 10 February 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Is your stock market still turned off?

Roger Montgomery

February 3, 2011

At this time of year, well-meaning articles on the subject of how to invest in the year ahead abound. Indeed I have contributed to the pool of wisdom in my recent article for Equity magazine titled Is your stock market on or off?.

At this time of year, well-meaning articles on the subject of how to invest in the year ahead abound. Indeed I have contributed to the pool of wisdom in my recent article for Equity magazine titled Is your stock market on or off?.Value.able Graduates know to turn the stock market off and focus on just three simple steps. Even if you have read Value.able, or joined in the conversation at my blog, its not just me that believes they’re worth repeating. Ashley wrote about the article ‘More of the same stuff for the Value.able disciples but the more you read it the more you will practise it’ and from David ‘’twas a good refresher indeed!’.

Step 1

The first step of course is to understand how the stock market works. Once you understand this, turning it off is easy. And you do need to turn of its noisy distraction.

Step 2

The second step is to be able to recognise an extraordinary business (Go to Value.able Chapter 5, page 057).

I have come up with what are now commonly referred to by Value.able Graduates as Montgomery Quality Ratings, or MQR for short. Ranking companies from A1 to C5, my MQR gives each company a probability weighting in terms of its likelihood of experiencing a liquidity event.

Step 3

Finally, the third step is to estimate the intrinsic value of that business. Use Tables 11.1 and 11.2 in Value.able.

Three simple steps. If you get them right, you too can produce the sorts of extraordinary returns demonstrated and published, for example, in Money magazine.

The key is to buy extraordinary companies. To save you some time, I would like share a current list of companies that don’t meet my A1 rating. Indeed these are the companies that receive my C4 and C5 ratings, the worst possible. Avoiding these is just as important as picking the A1s because even diversification doesn’t work when your portfolio is filled with poor quality companies or those purchased with no margin of safety.

Whilst the eleven companies listed above are low quality businesses, they won’t necessarily blow up. This is not exhaustive, nor is it a list of companies whose share prices will go down. It is however a list of companies that I personally won’t be investing in.

If your first question is what are the chances of loss?’ then my C5 rating represents the highest risk. But of course risk is based on probability. And a probability is not a certainty. Nevertheless, I prefer A1s and A2s. More on those lists another time.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 3 February 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

Will your portfolio repeat its 2011 performance?

Roger Montgomery

February 2, 2011

If you are new to my stock market Insights blog, welcome. And to the Value.able community, thank you for your many comments and encouraging words. It gives me great encouragement and motivates me to hear how your investing and returns have improved as a result of reading Value.able and the collection of comments posted by Graduates here at my blog. Thank you also for spreading the word and purchasing additional copies for family and friends.

If you are new to my stock market Insights blog, welcome. And to the Value.able community, thank you for your many comments and encouraging words. It gives me great encouragement and motivates me to hear how your investing and returns have improved as a result of reading Value.able and the collection of comments posted by Graduates here at my blog. Thank you also for spreading the word and purchasing additional copies for family and friends.Taking a look back over the stocks we discussed last year, it appears the Value.able approach to investing in the highest quality businesses, with a true margin of safety, has been doing quite well.

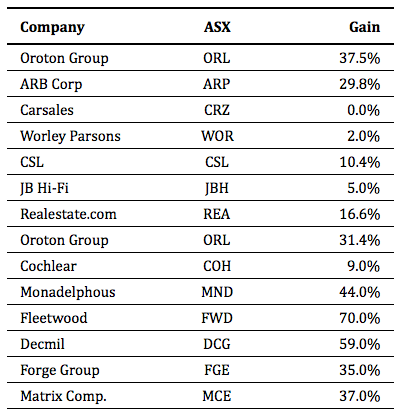

In addition to the blog, I also wrote about many of the stocks that achieve an A1 Montgomery Quality Rating (MQG) in my Value.able stocks for Money magazine over the last six months of 2010.

The stocks are listed in the table below. The column titled ‘Gain’ demonstrates you can do well without exposing yourself to lots of risk – for example the risk that is inherent in speculative stocks.

The returns exclude the dividends received, which would obviously boost results materially. The correct comparison therefore is the All Ords price index rather than the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index. Since 30 June 2010 the All Ordinaries has risen 12%. That is a stark contrast to many of the returns produced by the high quality businesses listed above.

The returns stand even higher above the Index when the selection is ranked by those that I regarded as offering the greatest margin of safety at the time the stock was mentioned: Oroton (up 37.5%), ARB Corporation (up 29.8%), JB Hi-Fi (bought and then sold the next month (up 5%), Monadelphous, Forge, Decmil and Matrix (up 44%, up 59%, up 35%, and up 37% respectively). The average, six month, price-only return of these businesses is 34.8%. And some of these A1 businesses, a margin of safety still exists.

If you are new to value investing you will, when searching around, find many commentators, portfolio managers and investors who may disparage value investing generally. They may question the method of calculating intrinsic value or even dismiss the valuations produced, but quite seriously, the proof is in the eating. And the returns offered have been nothing short of mouth watering.

But six months is NOT enough to hang your hat on, as Tony and Adam recently pointed out on my Facebook page. So if you have been an investor in any of these companies, following a conversation with your adviser of course, remember that the change in price over a year or two shouldn’t excite or concern you. It’s the change ahead in the Value.able intrinsic value of the company that matters.

If you haven’t already purchased your copy of Value.able, I commend it to you. It will change the way you think about investing in the stock market for the better, and as the many independent comments elsewhere here on the blog can attest, it may also materially improve your results. Value.able is available exclusively at www.rogermontgomery.com

Posted Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 2 February 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

TV this week?

Roger Montgomery

January 27, 2011

Tonight at 6.30pm on Today Tonight I will share my insights on a well known stock.

Tune into Channel 7 from 6.30pm Sydney time. More insights will be posted tomorrow.

An all-time record for the shortest post ever Posted by Roger Montgomery, 27 January 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

What does my 2031 crystal ball predict?

Roger Montgomery

January 13, 2011

I’m going to kick off 2011 with two things that I will unlikely repeat. Rather than look at individual companies today – something I am hitherto always focused on (and always will be) – I would like to share my insights, ever so briefly, into what I think are the major and possibly predictable themes for the next twenty years. The second? A 1781 word blog post.

I’m going to kick off 2011 with two things that I will unlikely repeat. Rather than look at individual companies today – something I am hitherto always focused on (and always will be) – I would like to share my insights, ever so briefly, into what I think are the major and possibly predictable themes for the next twenty years. The second? A 1781 word blog post.A word of warning… my track record at correctly predicting market direction is lousy. Thankfully this inability hasn’t hindered my returns thus far and probably won’t in the future.

Having provided that requisite warning, I invite you to consider the following thematic predictions (and yes, they are predictions).

1. Higher Oil Prices

The International Energy Agency (IEA), Energy Information Administration (EIA) and Platts Oilgram News have ‘confirmed’ that peak oil (maximum daily global oil production) was reached in 2005/06. With this backdrop, any hint of Chinese demand increasing and drawing down on spare capacity can cause significant price surges. It is interesting that prior to the last oil price spike, and when oil traded at $90/barrel, US unemployment was about 4%. If someone back then had asked you what the oil price should be in 2011 if US unemployment was more than double – you would not guess ‘still $90’.

It strikes me that there is a lot of demand for oil supporting the price that is not contingent on a strong US economy. China is the first that comes to mind. Other analysis reveals the Middle East, driven by the desire to be a global leader in the manufacture of plastic, is using much more oil than in the past.

And as Jim Rogers has regularly noted; if the US and global economies strengthen, demand for oil will increase. What if they don’t? Rogers anticipates the US Federal Reserve will print more money and the price of commodities will go up.

2. Higher Coal and Uranium Prices

Of the 6.8 billion people on Earth, over 3.5 billion have little or no access to electricity. Irrespective of greenhouse gas concerns, rising demand for energy will see coal’s current share increase. China and India will lead the demand. China’s demand shifted the country to net importer status in 2009 and by 2015 will more than triple consumption from 1990 levels. According to some reports, China is commissioning a coal-fired power plant every week.

In India coal generates three quarters of the country’s electricity, yet over 400 million people have no access to electricity. Demand for coal has risen every year for the past ten years. Some expect India will triple its coal imports in the next… wait for it… two or three years. Democracy hinders the ability of the government to install decent transport infrastructure (it can take six or seven hours to travel just 250 kilometers) and one would expect the same issues will prevent any substantial increase in the domestic mining of coal.

Don’t be surprised if there are more takeovers of Aussie coal companies.

Uranium has recently bounced 50 percent from the lows, but remains half the level of 2007 highs.

If the price of coal and oil rises, then the political opposition to uranium that has resulted in underutilisation of this resource (and of course constrained supply) will cause the price to rise materially.

According to the World Nuclear Association (WNA), global demand for uranium is about 68.5 thousand metric tons. Supply from mines is 51 thousand. The Russian and US megatons-to-megawatts program fills the shortfall, but clearly that provides only a short-term band-aid. So there is already a shortfall; currently, nearly 60 reactors globally are under construction and nearly another 150 are on order.

Late last year China increased its nuclear power target for the end of the new decade by 11 times its current capacity. And China plans to build more plants in the next ten years than the US has, ever.

On the supply side, new mines can take more than a decade to go from permit to production and while Australia has the largest reserve in the world, government debate has barely begun.

3. Higher Rubber Prices

Less than 50 people per 1000 own a car in China, and the country already consumes a third of the world’s rubber! The numbers elsewhere are three times that per thousand. It doesn’t matter whether those cars are electric, hybrid, diesel or petrol – the Chinese will need rubber for their car tyres.

On the supply side, rubber comes from trees predominantly grown in Asia. They take many years to mature and recent catastrophic weather has dented supply.

4. Weather, Weather everywhere

Many years ago my wife gave me a copy of The Weather Makers. In it Tim Flannery predicted the south-east corner of Australia would dry up and the northern states would experience increased rainfall. Whilst it seemed farfetched at the time, it was sufficiently concerning for me to put the purchase of a rural property in the North East of Victoria on hold. The 2009 Black Saturday bushfires and now, the devastating floods being experienced by 75 per cent of Queensland, are enough to convince me that Flannery’s predictions were prescient. The rest of the world has not been spared – the closure of Heathrow and JFK airports are testament to the fact that, irrespective of whether humans are responsible, the climate is changing.

Expect the price of agricultural products and foods to strengthen. This never occurs in a straight line so there will be bumps along the way, but food prices are going to rise and 140 year highs in cotton, for example, may be just the beginning.

Jim Rogers reckons you will be rich if you buy rice, and I would have to agree. Global increases in demand, supply shortfalls and then disruptions due to more violent weather patterns (La Niña notwithstanding) should be expected to dramatically increases prices.

Floods in Thailand (the world’s rice bowl) will cut production, insufficient monsoonal floods will cut production in Vietnam (the world’s second most important rice bowl) and freak weather elsewhere has meant other producing countries now rely more on imports. Rice is the staple for half the world’s population. Riots in 2007, when the price of rice hit a long-term high, offers an insight into how important this food is.

And as Jeremy Grantham said on CNBC: “We’re running out of everything”.

5. Inflation and Interest Rates

With wheat, cotton, pork and oats rising more than 50% last year and copper, sugar, canola and coffee up more than 30%, the inflation train has left the station, so to speak. Then there is the US Federal Reserve’s perpetual printing press – driving yields down and causing a currency tidal wave to flow to emerging countries, like China. Once the funds get there, they seek assets to buy, pushing their prices higher and thus exporting inflation elsewhere.

Despite this, in the US at least, the trend has been to invest in bonds. After being beaten to within an inch of their lives in stocks and real estate, there has been a love affair with bonds. The ridiculously low yields in bonds and treasury notes does not reflect the US’ credit worthiness and has caused some observers -including US Congressman Ron Paul (overseer of the US Fed) in Fortune magazine – to describe US Bonds as being in a “bubble”.

The Fed’s policies are geared towards low interest rates. But artificially-set low rates don’t reflect genuine supply and demand of money – they perpetuate a recession or at best merely defer it. The low rates trigger long-term investment by businesses even though those low rates are not the result of an increase in the supply of savings. If savings are non-existent, then the long-term investment by businesses will produce low returns because customers don’t have the savings to purchase the products the businesses produce. But that is a side issue.

The US, for want of a better description, appears to be bankrupt. A country with the poorest of credit ratings and living off past victories will not forever be offered the ability to charge the lowest interest rates. And China won’t continue to allow itself to be the sponge that absorbs US dollars either. Indeed at the start of this year, China allowed its exporters – for the first time – to invest their foreign currency directly in the countries they were earned. No longer do they have to repatriate foreign funds and hand them to the Peoples Bank of China in return for Yuan. This is a solution that Nouriel Roubini didn’t consider in his article – how China may respond to inflows that inevitably drive up its exchange rate, published in the Financial Review late last year.

5a. Expect US interest rates to rise

Inflation in the US has been held down in the first instance, arguably, by some questionable number crunching, but also by the export of deflation by China to the US. Now the inflation train has left the station (coal, uranium, food, agriculture, rubber et. al., Chinese input costs will go up – because its currency hasn’t (to help its exporters remain competitive)) – and the ability of the US to continue to report benign inflation numbers becomes problematic.

If inflationary expectations rise, so will interest rates. Declining bond prices will again dent the investment performance of pension funds that have been pouring into treasury and municipal bonds (they’re another fascinating story – Subprime Mk II). In turn, the ageing US consumer will feel the double impact of poor present economic conditions and poor retirement prospects.

Over in China, even if the government tries and mitigate inflation by simply capping prices, suppliers won’t invest in additional capacity and the resultant restriction in supply will simply defer, but not prevent, even higher prices.

Tying it all together

It’s far easier to invest when the tide is rising and it is also easier to make profits in businesses when your pool of customers is expanding and becoming wealthier. Value.able investment opportunities (extraordinary businesses at big discounts to intrinsic value) will be found in companies that sell products and services to Asia and India (from financial to construction), as well as those that stand to benefit from the ongoing impact of rising demand for, and [climate] effects on, food and energy etc. These opportunities will dominate my thoughts this year and this decade and I believe they should guide yours too.

So now I ask you – the Value.able Graduate Class of 2010 and Undergraduate class of 2011. What are your views, predictions and suggestions? Which companies do you expect to benefit the most? Be sure to include your reasonings.

I will publish my Montgomery Quality Rating (MQRs) and Montgomery Value Estimate (MVE) for each business you nominate in my next post, later this month.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 13 January 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

After some extra help with your holiday homework?

Roger Montgomery

January 6, 2011

Happy new year! I trust you had a safe, peaceful and Happy Christmas.

Happy new year! I trust you had a safe, peaceful and Happy Christmas.To the Value.able Graduates, thank you for sharing your knowledge and taking the time to help the Undergrads with their holiday homework.

If you are seeking a little extra guidance, this Masterclass video I recorded for Alan’s Eureka Report may just do the trick. Think of it as Value.able‘s Chapter 11, Steps A-D and Steps 1-4, live.

If you have not already secured your copy of Value.able and want to kick 2011 off the Value.able way, go to www.RogerMontgomery.com. The First Edition sold out in just 14 weeks and with so many private and professional investors now buying multiple copies for friends and family, the Second Edition is set to sell out just as quickly. Don’t waste another minute!

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 6 January 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Thank you and Happy Christmas

Roger Montgomery

December 23, 2010

I am delighted that, in 2010, so many investors have found Value.able useful. Many Graduates have said the Value.able approach to investing is at once easy to understand and rational. And according to John, Scott, Brian, Peter, Andy, Martin and Steve’s feedback, Value.able!

Merry Christmas Roger! And a big thankyou for writing your book.

It never ceases to amaze me just how few professional investors actually stick to a winning investment formula. I recently reviewed the portfolio holdings of many well known Australian Equity managed funds available through a major online broker and could not find one “leading” fund manager that only invested in stocks that would come anywhere near to passing the MQR (Montgomery Quality Rating) test. Virtually all major funds hold stocks that are low ROE, highly capital intensive and debt laden. Unfortunately, I was not surprised to see that many of these funds holding large positions in non-investment grade stocks proudly highlight their 5 star ratings from asset consultants.

Have a well-earned break and may 2011 be an in-value.able year for you and yours,

Warmest regards,

JohnMerry Christmas everybody! And to you Mr Montgomery, a massive thank you.

Thanks to your wonderful book, and your insightful and thought provoking articles, posts and appearances. My SMSF has had the best year ever (that’s with 10 years of history).

In a lack lustre sideways market I was able to pinpoint and cut out the dead wood from previous poor decisions, and focus on quality businesses trading at a big discount to IV.

The difference in fund performance is simply startling.

Again thank you, I hope to be able to shake your hand again in 2011.

All the best

Scott THi Adam & Roger, … I’m pleased I’m getting the hang of these valuations. I’ve bought a few other A1’s also, MCE, SWL (A3) & FGE on my research following your valuation criteria Roger, as well as JBH. I’m getting rid of some rubbish (AMP,BFG,VMG,BYL) & feel confident I’m replacing them with quality shares. Thanks so much for sharing Roger, my retirement looks a little more hopeful now following the devastation of the GFC.

Brian

Hi Roger, Thanks for writing the book and your diligence in keeping the blog up to date. You’ve made a massive contribution to my awareness and knowledge. The book has already been paid for hundreds of times over.

Cheers, Peter

Roger, Thanks for all the great insights over the last year. I really had no idea how blindly I had been investing prior to reading your book and this blog. I’m still learning but at least I know what I should be looking at now.

Thanks again

Andy

Hi Roger, Just wanted to thankyou for sharing your knowledge and insights with everyone, your book was amazing to say the least!!! I’ve made a return of close to 20% in less than 6 months and your Value.able book has paid itself off by more than 200 times!!! Now that is what I call ROE. I would like to wish you and your family a Merry Christmas and a happy new year. Thank you so much for an extremely valuable year, congrats and best wishes.

Regards,

Martin

Hi Roger, I see many comments on the blog congratulating you on your book, but they don’t actually say why it is great. So I have done a book review.

Regards,

Sapporo Steve

If you have not already secured your copy of Value.able and want to kick 2011 off the Value.able way, go to www.RogerMontgomery.com. The First Edition sold out in just 14 weeks and with so many private and professional investors now buying multiple copies for friends and family, the Second Edition is set to sell out just as quickly. Don’t waste another minute!To the Value.able Graduates, thank you for taking the time to share with me just how much you have been impacted by my book. I am delighted to hear your amazing stories of investing success and I am pleased we can sign off 2010 with such an extraordinary investment track record.

I wish you all a safe, peaceful and Happy Christmas and my sincere best wishes for 2011. I have always been enthralled by Caravaggio’s work. The Adoration was painted in 1609.

My office will close today and reopen on Monday 10 January. I will return in late January. My team will continue to publish your comments here at the blog, post new videos to my YouTube channel and reply to your emails. Most importantly, my website will continue to accept your Value.able orders and my distribution house is working through the holiday season.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 23 December 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Have you done your homework?

Roger Montgomery

December 22, 2010

As my last official day at the office draws near, I am delighted with the results we have achieved from combining my approach to quality (The Montgomery Quality Ratings “MQRs”) with Value.able‘s method of calculating intrinsic value. There will always be conjecture and disagreement with these, but that doesn’t matter to me and it shouldn’t bother you either. The market is wide enough and deep enough to cater for us all.

As my last official day at the office draws near, I am delighted with the results we have achieved from combining my approach to quality (The Montgomery Quality Ratings “MQRs”) with Value.able‘s method of calculating intrinsic value. There will always be conjecture and disagreement with these, but that doesn’t matter to me and it shouldn’t bother you either. The market is wide enough and deep enough to cater for us all.I am very proud of how far you – the Value.able Graduate Class of 2010 – have come and encourage you to continue questioning and challenging the things you read and learn. It was Elbert Hubbard who said “The recipe for perpetual ignorance is: Be satisfied with your opinion and content with your knowledge.”

Some of the most memorable results of 2010 for me where the gains in Matrix, Decmil and Forge, as well as the gains in Acrux, Thorn, Fleetwood, MMS, Data#3, and Oroton. I was also delighted to have left QR National alone – missing out on an 11.8% return, but selecting MACA instead, which has produced a 70 per cent return.

Elsewhere, fund managers have reported good results. But as one Graduate noted via email, when some portfolios, filled with debt-laden, low ROE businesses, rise, it is generally a function of a rising tide rather than sound investing principles. Of course when investing the Value.able way, it matters not what anyone else is doing. All that matters is that your analysis is right and that you are consistent.

There have been plenty of questions about the Value.able valuation formula this year and perhaps even a little obsession over the source of, reason for and disagreement with the formula/tables. If that resonates with you, I urge you to re-read pages 193 and 194 and consider the following parallel; In the sport of mountain biking, some riders obsess with the weight of their bicycles. Many shop around for a ceramic or titanium rear derailleur pulley so that they might save as few as 5 grams! Paying thousands for their obsession, they fail to realise that the weight of their fettucini carbonara the night before, the water bottle they carry with them and the mud that sticks to their tyres is far greater than the savings they make and that strength, fitness, endurance and momentum are all far more important. Don’t become too obsessed by the math when its the competitive advantage that is more important and, in any case, value slaps you in the face when it is obvious.

There are very good reasons why my valuations have differed from those you have produced, and I explain a major source of the difference on pages 193 and 194.

Far more important is that you are now carrying out your own analysis and focusing your attention on high quality companies, sustainable competitive advantages and intrinsic value. I believe you will continue to do well – as so many of you have shared with our community – if you stick to the disciplines outlined in Value.able. And if you haven’t purchased your copy yet, do it now!

Before I leave for the annual Montgomery family holiday, I promised to give you some homework. There are three tasks with a total of two challenges. You can choose those you’d like to complete. You are under no pressure to complete them all. It is the holidays after all!

Challenge 1, Task 1

The first task is to print out the Notes to the Financial Statements: Contributed Equity for the number of shares on issue, Balance Sheet, Profit and Loss statement and Statement of Changes in Equity for The Reject Shop for 2010. Links to the statements are below:

Notes to the Financial Reports: Contributed Equity for the Number of Shares on Issue – click here

Balance Sheet – click here

Profit and Loss – click here

Statement of Change in Equity (Dividends) – click here

Using the numbers circled on each of the statements and a Required Return of 11%, try your hand at calculating The Reject Shop’s 2010 Value.able Intrinsic Value. Follow Steps A through D on page 195 of Value.able. Be sure to list your outputs for Equity per Share, Return on Equity and Payout Ratio. Click here to download my Value.able Valuation Worksheet. Ken has also provided a great list of guidelines – click here.

Challenge 1, Task 2

If you want to obtain extra marks you can have a go at also calculating the 2010 cash flow for The Reject Shop using the method I outline in Value.able on page 152.

If you haven’t purchased Value.able, don’t worry. My website will continue to accept your orders and my distribution house is working through the holiday season.

Challenge 1, Task 3

The final task involves completing one or both challenges on the Christmas Holiday Spreadsheet. The first challenge is for Value.able Undergrads. Use the worksheet to fill out the spreadsheet, then rank the companies by their Safety Margin. The spreadsheet will download automatically to your computer. When I return in late January I will publish my table and we can compare results.

Challenge 2

The second challenge is for the Value.able Graduate Class of 2010 (and any Undergrads that fancy a challenge). Your task is to calculate the historical change in intrinsic value and price over the last ten years.

Don’t worry. You don’t have to calculate ten intrinsic values, just two. Estimate the intrinsic value a decade ago (2001) and compare it to the 2011 intrinsic value. To make things a little less onerous, maintain the same RR for a company for the two years. You can then rank the five companies by their rate of change and you can use the following formula in excel if you like:

((IVn/IVn-10)^(1/10))-1

Where, IVn is Intrinsic value for 2011 and IVn-10 is Intrinsic Value for 2001 and ^(1/10) is ‘to the power of 1/10’.

I expect it will take a few weeks for you to get all the your submissions and I will consider some form of recognition for the winners. In the meantime enjoy a peaceful and Value.able Christmas and all the very best to you and your loved ones.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 22 December 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Merry Christmas from the Value.able Graduate class of 2010

Roger Montgomery

December 21, 2010

It is my great pleasure to present a very special tribute (thank you to my team) for the Value.able Graduate Class of 2010.

Thank you Jesse, Michael (Bali), Young Les, Michael (Aussie Battler), Matthew, Justin, Lior, John, Rad, Gary in Paris, George, Dan’s Mum, Steven & Sophie, the Master Chefs, John and Paul for sharing your Value.able journey with our community. And a second thank you to Steven for posting his Value.able 12 Days of Christmas at Facebook!

Thank you for your support this year. We have created an incredibly valuable community of investors that share sound ideas and mentor those just beginning their value investing journey.

Thanks to you – the Value.able community – 2010 year has been a year of firsts…

The First Edition of Value.able was released, went global and sold out in just 14 weeks.

- – Montgomery Quality Ratings (MQR) are appearing in conversations all over the world.

– My value investing YouTube channel hit #2 Most Viewed in Australia.

– In aggregate, the companies I listed at my Insights blog, which met all the Value.able criteria, outperformed the market by a satisfactory margin.

Most excitingly, Value.able Graduates have applied their new skills and produced over 6,000 extraordinarily insightful comments here at the blog!

And one more thing… for those who have requested holiday homework, my soon-to-be-released blog post will most certainly provide a challenge.

Thank you once again for joining the Value.able community. I wish you and your family a safe and peaceful Christmas and a prosperous 2011.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 21 December 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.