Investing Education

-

Who asked for Easter holiday homework?

Roger Montgomery

April 14, 2011

My team tell me that this year’s combination of Easter and Anzac Day has produced a once-in-a-lifetime succession of public holidays. I have encouraged them to use the time wisely – practicing Value.able intrinsic value calculations. In addition to spending precious time with family and friends, I encourage you to do the same.

My team tell me that this year’s combination of Easter and Anzac Day has produced a once-in-a-lifetime succession of public holidays. I have encouraged them to use the time wisely – practicing Value.able intrinsic value calculations. In addition to spending precious time with family and friends, I encourage you to do the same.We have an extraordinarily generous community of Value.able Graduates here at the blog and on my Facebook page. Special thanks to Ashley, Kent B, Lloyd, Rob, Matt R, Steve, Andrew, Gavin, Ken, William (Bill), Greg, John M, Ron, Joab (whom we will miss dearly – please keep in touch), Jonesy, Brad, Ann, O’Reilly, James, Trav, Omar, Michael, Costas, Emily and Anthony. If I have left anyone out please let me know. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with our community! I am sure there are many others who are delighted to help recent Graduates.

Before I reveal your Easter homework, here are a couple of links you may find helpful:

Webinar – I guide you, step-by-step, through a valuation

Data sources – The Value.able community’s guide to finding the data you need to calculate your own valuations.

Now to the homework…

I began with 1847 businesses and removed the 1168 that didn’t make any money last year (put $0 into the Value.able formula and you will get $0 out). That cut out 63 per cent of the Australian market… a useful first filter.

Then I applied the following criteria;

1) ROE > 20 per cent: (Chapter 6 – The ABC of Return on Equity)

2) Debt/Equity Ratio < 50 per cent: (Chapter 8 – Debt Is Not Always Good)

And then I refined the list further as follows;

3) 2011 forecast Earnings and Dividends are available: (Chapter 5 – Pick Extraordinary Prospects)

4) Must achieve one of the following Montgomery Quality Rating (MQR) – A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3: (Part Two – Identifying Extraordinary Businesses)

That left 255 stocks as the subject of your holiday homework. Using my discretion, I reduced the list to 14: The Reject Shop (ASX:TRS/MQR:A2), West Australian Newspapers (ASX:WAN/MQR:A2), Computershare (ASX:CPU/MQR:A2), Mermaid Marine (ASX:MRM/MQR:A3), Flexigroup Limited (ASX:FXL/MQR:A3), Cedar Woods Properties (ASX:CWP/MQR:A3), SAI Global Limited (ASX:SAI/MQR:B2), Fortescue Metals Group (ASX:FMG/ MQR:B2), Coca-Cola Amatil Limited (ASX:ASX:CCL/ MQR:B2), Retail Food Group (ASX:RFG/ MQR:B3), Telstra (ASX:TLS/ MQR:B3), McMillian Shakesphere (ASX:MMS/ MQR:B3), Bradken Limited (ASX:BKN/ MQR:B3) and Aristocrat Leisure Limited (ASX:ALL/ MQR:B3).

This homework is not about finding cheap stocks – it is about understanding businesses, return on equity, debt, cashflow and identifying extraordinary prospects. Effort calculating intrinsic value should only be exerted once you’re satisfied the business is extraordinary.

If you are keep to improve your investing with some useful examples, your holiday homework is as follows:

1. Download the 2011 Easter holiday homework worksheet – click here.

2. Calculate the 2010 Value.able intrinsic value and 2011 forecast Value.able intrinsic value (populate into the worksheet)

3. Then answer the following questions and perform the following tasks:

A. Of the 14 companies, list those demonstrating a rising value over the next twelve months.

B. The stocks of which companies, if any, are offering a margin of safety?

Important things to note:

- For consistency, use 10% Required Return

- 2011 Forecast Earnings Per Share and Dividends Per Share numbers are included in the Easter holiday homework spreadsheet. Use these numbers.

- You will have to get the 2010 ending equity (which is also the 2011 Beginning equity – from the annual reports)

If you need some guidance about how to calculate future valuations you can also read this post.

For those seeking a real challenge, re-read Value.able Chapter 9 on Cashflow (from page 152) and analyse the cashflow of each company using the balance sheet method. Click here to download the Cash Flow homework worksheet. At Montgomery Investment Management we only invest in businesses with strong cash flow. I will produce the cash flow analysis for The Reject Shop (TRS), Retail Food Group (RFG) and Aristocrat Leisure (ALL) after Easter.

My team and I wish you a happy Easter. I really do hope you have an enjoyable and rewarding break and that you enjoy the tasks I have set for you. I look forward to reviewing your results after the break.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 14 April 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Investing Education.

-

10,000 Comments and Counting

Roger Montgomery

April 13, 2011

Early this month we hit a milestone worth celebrating. Thanks to your incredible interest in the value investing approach advocated and discussed here we hit 10,000 comments.

Thank you for your interest, your passion and your generosity. It is amazing and I cannot be more proud of the incredibly diverse directions you have all headed with the new found knowledge from Value.able.

Thank you also for your encouragement and taking the time to share with me just how much you have been impacted by Value.able. My team and I are delighted to hear your amazing stories of investing success.

Speaking of stories, here is one of my recent favourites. It’s from Craig, a Graduate from the Value.able Class of 2010. It’s the story of Eddie and his bike…

Twelve year old Eddie has a paper round.

He bought a bike for $10,000 (its a bloody good bike) and earns $1,000 a year, after all expenses (new tyres, chewing gum) and tax (there’s no tax as the bloke who owns the newsagency pays him cash).

Eddie’s happy, but he wants a new playstation, so he offers a 50% share in his operation to family members.

His brother’s keen but the $10 he gets for mowing the front lawn (the backyard is fake grass) means he doesn’t have the money.

His teenage sister is keen but she’s running up huge mobile phone bills which accounts for all of her pay from McDonald’s.

His old girl’s keen but she just bought a new Apple product, so she’s got no money to spare.

His old man however, has squirreled away $5,000 by doing some overtime at work, and had been shopping around for somewhere to put it to work. ING are offering 8% (this is 2013), so the old man says to Eddie: “Look son, I can get 8% at the bank.”

“You can get 10% with me dad, if you hand over that 5 grand.”

“Yeah but you might want to do something else one day, or your bike could need replacing, or you could – god forbid son – have an accident. With all that risk involved, I wan’t 12.5%, so I’ll give you $4,000 for me half share.”

“Four large? You’re killing me dad. Don’t you know banks can go broke?”

“Not in this country son. I want 12.5%.”“There’ll be another GFC, you wait, but people will still want the paper delivered.”

At that point, the boy’s mother approaches, holding her new iPad.

The husband looks at her, then back to his son: “Make it $2,500… I want 20%.”

What is your funny or amazing Value.able story?

Go ahead, Share, Encourage and Inspire. And thank you for helping so many investors value the best stocks and buy them for less than they are worth!

Did you contribute your photo to the Value.able Graduate Class of 2010? The Class of 2011 is open and accepting Graduates. Email your photo and join Bernie, Martin, Alya and Jim Rogers.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 13 April 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Is Oroton Australia’s best retailer?

Roger Montgomery

April 12, 2011

Oroton, JB Hi-Fi, The Reject Shop, Woolworths, Nick Scali, Cash Converters. If you have seen me on Sky Business or visited my YouTube channel recently, these names will be familiar. David Jones, Country Road, Harvey Norman, Myer, Super Retail Group (think Super Cheap Auto), Strathfield Group (Strathfield Car Radios), Noni B and Kathmandu also spring to mind, albeit for different reasons.

As a business, retailers are relatively easy to understand. The best managers are easy to spot (think Oroton’s Sally MacDonald) and it is also easy to separate the businesses with earnings power from those without (compare JB Hi-Fi and Harvey Norman).

But generally speaking even the best retailers may not be companies you want to hold forever. Why? Because they quickly reach saturation and so must constantly reinvent themselves.

Barriers to entry are low. There are always new concepts with young, intelligent and energetic entrepreneurs eager to develop a new brand and offering. Big red SALE signs are replacing mannequins as permanent window fixtures in Australian shop fronts, driving down revenue and margins. And for those who choose to defend brand value, sales revenue is also often sacrificed.

Then there’s the twin-speed economy, a string of natural disasters, soaring oil prices, growing personal savings, higher interest rates, Australia’s small population and one that is increasingly adept at shopping online for a getter price. Hands up who wants to be a retailer?

Retailers are attractive businesses – at the right price and the right stage in their life cycle. So, in retailing, who is Australia’s good, bad and just plain ugly?

Remember, these comments are not recommendations. Conduct your own independent research and seek and take professional personal advice.

Harvey Norman

ASX:HVN, MQR: A3, MOS: -19%A decade ago Gerry’s retail giant earned $105 million profit on $484 of equity that we put in and left in the business. That’s a return of around 19 per cent. Fast-forward to 2010 and we’ve put in another $117 million and retained an additional $1.5 billion. Despite this tripling of our commitment, however, profits have little more than doubled to $236 million. Return on equity has fallen by a third and is now about 12%. One decade of operating and the intrinsic value of Harvey Norman has barely changed. HVN is a mature business, but be warned… Harvey Norman is what JB Hi-Fi and The Reject Shop would see if they used a telescope to look forward through time.

OrotonGroup Limited

ASX:ORL, MQR: A1, MOS: -21%Sally MacDonald is a brilliant retailer. I highly recommend watching this interview – click here. Sally took over Oroton in 2006. In just five years she has cut loss making stores and brands, sliced overheads, improved both the quality and diversity of the range. The result? Surging revenues and return on equity in 2010 of circa 85 per cent. Try getting that in a bank account or even a term deposit! Asia offers even brighter prospects for Oroton while their product offering is sufficiently attractive and appealing that the company has the ability to weather the retail storm and protect its brand.

Woolworths Limited

ASX: WOW, MQR: B1, MOS: -17%You don’t get any bigger than Woolworths (its one of the 20 largest retailers on the planet!). It has a utility-like grip on consumers only, with earnings power that would put any utility to shame. The latter can be seen in the near 30% annualised increase in intrinsic value. Competitive position and size means suppliers and customers fund the company’s inventory. Challenges included professed legislative changes to poker machine usage (WOW is the largest owner of poker machines and any drag in revenue will have an exponential impact on profits), and the rollout of a competitor to Bunnings.

David Jones Limited

ASX: DJS, MQR: A2, MOS: -35%A beautiful shop makes not a beautiful business. I remember when David Jones floated. Shoppers who enjoyed the ‘David Jones’ experience and were loyal to the brand bought shares with the same enthusiasm as scouring the shoe department at the Boxing Day sales. Since 2007 DJS has reduced its Net Debt/Equity ratio from 108 per cent to just under 12 per cent. We are yet to see if Paul Zahra can lead DJs with the same stewardship as former CEO Mark McInnes but as far as department stores can possibly be attractive long-term investments, DJs isn’t it.

Myer

ASX: MYR, MQR: B1, MOS: -27%In 2009, following the release of that gleaming My Prospectus, I wrote:

“With all the relevant data to value the business now available and using the pro-forma accounts supplied in the prospectus, I value the company at between $2.67 and $2.78, substantially below the $3.90 to $4.90 being requested [by the vendors]. It appears to me that the float favours existing shareholders rather than new investors.”

My 2011 forecast value for Myer is just over $2. According to My Value.able Calculations, Myer will be worth less in 2013 than the price at which it listed in September 2010. If competitors like David Jones, Just Jeans, Kmart, Target, Big W, JB Hi-Fi, Fantastic Furniture, Captain Snooze, Sleep City, Harvey Norman, Nick Scali and Coco Republic were removed, Myer may just do alright.

Noni B

ASX: NBL, MQR: A2, MOS: -51%Noni B’s intrinsic value is the same as when Alan Kindl floated the company in 2000 (the family retained a 40% shareholding). Return on Equity hasn’t changed either. Shares on issue however have increased 50 per cent yet profits have remained relatively unchanged.

Kathmandu Holdings Limited

ASX: KMD, MQR: A3, MOS: -56%Sixty per cent of Kathmandu’s revenues are generated in the second half of the year. Will weather patterns continue to feed this trend? I sense premature excitement following the implementation of KMD’s newly installed intranet. The system may streamline store-to-store communications, reducing costs and creating inventory-related efficiencies for the 90-store chain, however what’s stopping a competitor replicating the same out-of-the-box system?

Fantastic Furniture

ASX: FAN, MQR: A3, MOS: -24%Al-ways Fan-tas-tic! Once upon a time it was. Low barriers to entry are seeing online retro furniture suppliers like Milan Direct and Matt Blatt are forcing Fantastic and other traditional players to reinvent the way they display, price and stock inventory.

Billabong

ASX: BBG, MQR: A3, MOS: -49%Billabong’s customers are highly fickle, trend conscious and anti-establishment. Like Mambo, as one of my team told me, Billabong is “so 1999 Rog”. Apparently Noosa Longboards t-shirts fall into the “cool” category, now. Groovy!

Eighty per cent of Billabong’s revenues are derived from offshore. Every one-cent rise in the Australian dollar has a half percent negative impact on net profits. Fans of the trader Jim Rogers believe the AUD could rise to USD$1.40! Then there’s the 44 stores affected by Japan’s earthquake (18 remain closed) and another three in the Christchurch earthquake.

Country Road

ASX: CTY, MQR: A3, MOS: -63%).Like the quality of their clothing, Country Road’s MQR has been erratic. So too has its value. Debt is low however cash flow is not attractive. Very expensive.

Cash Convertors

ASX: CCV, MQR: A2, MOS: +26%.Value.able Graduates Manny and Ray H nominated CCV as their A1 stock to watch in 2011. Whilst its not yet an A1, Cash Convertors is a niche business with bight prospects for intrinsic value growth.

Other retailers to watch

I have spoken about JB Hi-Fi, Nick Scali and The Reject Shop many times on Peter Switzer’s Switzer TV and Your Money Your Call on the Sky Business Channel. Go to youtube.com/rogerjmontgomery and type “retail”, “JBH”, “TRS” or “reject” into the Search box to watch the latest videos.

In October 2009 the RBA released the following statistics:

16 million. The number of credit cards in circulation in Australia;

$3,141. The average monthly Australian credit card account balance;

US$56,000. The average mortgage, credit card and personal loan debt of every man, woman and child in Australia;

$1.2 trillion. The total Australian mortgage, credit card and personal loan debt;

$19.189 billion. The amount spent on credit and charge cards in October 2009.Clearly we are all shoppers… what are your experiences? Who do you see as the next king of Australia’s retail landscape?

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 12 April 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Another warning Roger?

Roger Montgomery

April 8, 2011

Last night on Peter’s Switzer TV I shared five stocks moving up the Montgomery Quality Ratings (MQR) – B3 to A3, C4 to B3, A4 to A3, C5 to A2 and A4 to A2.

Last night on Peter’s Switzer TV I shared five stocks moving up the Montgomery Quality Ratings (MQR) – B3 to A3, C4 to B3, A4 to A3, C5 to A2 and A4 to A2.There are about thirty-seven ratios that contribute to the Montgomery Quality Rating. Like the Value.able method for valuing businesses, the MQR is my own unique system of assessing the quality and performance of businesses. Its objective is to weed out those with a high risk of catastrophe and highlight those with a very low risk.

I also spoke about Zicom, a very thinly traded micro-cap that we began buying for the Fund at $0.32, up to $0.42. Yesterday Zicom closed at $0.52 – my estimate of its Value.able intrinsic value.

If you read my ValueLine column for Alan’s Eureka Report on Wednesday evening you will recognise the following warning:

A WARNING FROM ROGER MONTGOMERY: The subject of today’s column is a thinly traded microcap in which I have bought shares because it meets my criteria. It may not meet yours. It is therefore information that is general in nature and NOT a recommendation or a solicitation to deal in any security. The information is provided for educational purposes only and your personal financial circumstances have not been taken into account. That is why you must also seek and take personal professional advice before dealing in any securities. Buying shares in this company without conducting your own research is irresponsible. Buying shares in this company will drive the price up, which will benefit me more than you. The higher the price you pay the lower your return. If the share price rises well beyond my estimate of intrinsic value, I could sell my shares. A share price that rises beyond my estimate of intrinsic value is one of my triggers for selling. I have no ability to predict share prices and despite a margin of safety being estimated, the share price could halve tomorrow or worse. There are serious and significant risks in investing. Be sure to familiarise yourself with these risks before buying or selling any security. Further, my intrinsic value could change tomorrow, if new information comes to light or I simply change my view about the prospects of a company. This could be another trigger for me to sell. Value investing requires patience. You must seek and take personal professional advice and perform your own research.

I reiterated these same concerns last night with Peter (and early last year I wrote a blog post specifically about the problem).

With those warnings in mind, here are the highlights from Peter’s show.

What stocks are on your ‘Improving MQRs’ watchlist? Thank you in advance for sharing your ideas with our Value.able community.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 8 April 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Will David beat Goliath?

Roger Montgomery

April 6, 2011

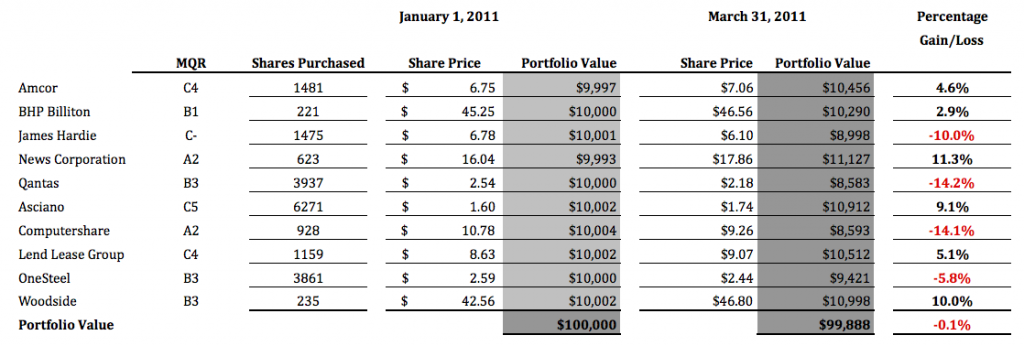

I am deviating from my regular style of post, handing over the stage to Value.able Graduate Scott T. Scott T has taken up a fight with conventional investing by tracking the performance of a typical and published ‘institutional-style’ portfolio against a portfolio of companies that receive my highest Montgomery Quality Ratings. I reckon in the long run the A1/A2 portfolio will win, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

I am deviating from my regular style of post, handing over the stage to Value.able Graduate Scott T. Scott T has taken up a fight with conventional investing by tracking the performance of a typical and published ‘institutional-style’ portfolio against a portfolio of companies that receive my highest Montgomery Quality Ratings. I reckon in the long run the A1/A2 portfolio will win, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.Over to you Scott T…

In December 2010, a large international institution released their “Top 10 stockpicks for 2011”. Click here to read the original story.

I thought it would be interesting to compare the performance of these suggestions against an A1 and A2 Montgomery portfolio.

So I imagined this scenario…

Twin brothers in there 30’s each inherited $100,000 from their parent’s estate. One was a conservative middle manager in the public service; he had little interest in the stock market or super funds and the like, so he decided to go to an internationally renowned, well-credentialed and highly respected firm to gain specific advice. Goldman Sachs advised him of their top ten stocks for 2011, so he decided to achieve diversification by investing $10,000 in each of the ten stocks he had been told about.

His twin had a small accounting practice in a regional Queensland and was a keen stock market investor. Specifically he was a student of the Value Investing method, and liked to think of himself as a Value.able Graduate. He too thought diversification would be a suitable strategy so decided to invest $10,000 in each of 10 stocks that were A1 or A2 MQR businesses and that were selling for as big a discount to his estimate of Value.able intrinsic value as he could find.

For this 12-month exercise, running for a calendar year, we shall assume that neither brother is able to trade their position. One brother has no inclination to, and his regional twin is fully invested, and more inclined to hold long anyway.

For the companies who have declared dividends in this quarter, most are now trading ex-dividend, but only 2 or 3 have actually paid. Dividends will be picked up in Q2 and Q4 of this study.

Now after just 3 months let’s look at the how the two portfolios have performed…

Institutional Bank Top 10 Picks for 2011

Montgomery Quality Rated (MQR) A1 and A2 Companies

We will visit the brothers again in 3 months on 30/6/2011 to see how they are fairing.

All the best

Scott T

How has your Value.able portfolio performed compared to the ASX 200 All Ords?

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 6 April 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Why idolise the iPad2?

Roger Montgomery

March 29, 2011

It’s an amazing story… Man creates computer. Man overcomplicates computer. Man strips back computer and creates a brand that has revolutionised the way we are entertained.

It’s an amazing story… Man creates computer. Man overcomplicates computer. Man strips back computer and creates a brand that has revolutionised the way we are entertained.Did you know Apple has sold over 300 million iPods and iPhones over the past decade? That’s 300,000,000 products. According to the World Bank, in 2009 the world’s population stood at 6,775,235,741. The World Bank also notes that 80 per cent of the world’s population lives on less than $10 per day. Of the remainder, every 4th man, woman and child has purchased an Apple products in the last decade. Not a bad competitive advantage, (postscript: but perhaps not a sustainable one?)

Apple is also infiltrating the way we work. The Montgomery office is all Mac (and for your information, we have never had to call an IT professional to fix anything). Our iPhones are synced with our iMacs and our MacBooks synced with our iPhones.

You have heard the stories of Apple fans setting up camp on the footpath outside Apple’s flagship store on Sydney’s George Street. Australians don’t do that for coal or iron ore.

And don’t forget the accessories market. There’s no special concessions for development partners. Privately held companies that manufacture the sleeves, cases and connectivity devices that enhance our Apple experience don’t get hold of new devices until we do – on launch day.

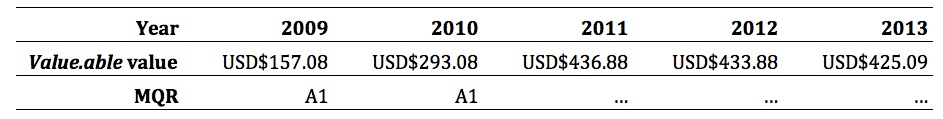

Apple has the X-factor. Its product is unique. Its experience is unique and there is an almost religious fervour toward the brand. Competitors don’t stand a chance. The result? High, durable rates of return on equity and a rising Value.able intrinsic valuation – an A1 business.

Return on Equity is just one of dozens of metrics I uses to produce the Montgomery Quality Rating (MQR). Re-read Chapter Eleven, Step C on page 188 of Value.able for the Value.able ROE calculation.

Who is the Aussie equivalent? The Australian market may be much smaller than the US, but there are a handful of extraordinary businesses, A1 businesses. And its worth finding tem. They may not be listed yet. They may not even have launched yet…

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 29 March 2011.

Postscript: The data used to calculate intrinsic value is available here: https://www.apple.com/investor/

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

When to sell? Matrix and other adventures in Value.able Investing

Roger Montgomery

March 18, 2011

In August 2010 Matrix Composites & Engineering, when we first began commenting on the company, was trading around $2.90. Thirty days later the share price was at $4.48. Today MCE is trading at just over $9.00 and has a market capitalisation of more than half a billion dollars. It’s no longer just a little engineering business. Like the Perth industrial precinct of Malaga in which its headquarters are based, MCE is growing rapidly (according to Wikipedia there are currently 2409 businesses with a workforce of over 12,000 people in Malaga. The 2006 census listed only 28 people living in the suburb).

But has MCE’s share price risen beyond what the business is actually worth?

Stock market participants are very good at telling us what we should buy and when. When it comes to selling, it seems silence is the golden rule.

If you receive broker research, take out a report and turn to the very back page – the one beyond the analyst’s financial model. You will often find a table that lists every company covered by that broker’s research department. Now look to the right of each stock listed. What do you notice?

Buy… Buy… Hold… Buy… Buy… Accumulate… Hold…

What about sell?

There aren’t many companies in Australia worthy of a buy-and-hold-forever approach. And if you have invested in a company with a previous BUY recommendation, the luxury of a subsequent Ceasing Coverage announcement by the analyst is not helpful.

So then, when should you sell? It is a question I have been asked, to be honest, I can’t remember how many times. Because I have been asked so many times, it’s a question I answered in Chapter 13 of Value.able – a chapter entitled Getting Out.

Value.able Graduates will recognise a sell opportunity. Yes, it is an opportunity. Fail to sell shares and you could eventually lose money.

Of course, any selling must be conducted with a certain amount of trepidation, particularly when capital gains tax consequences are considered. But not selling simply because of tax consequences is unwise.

We pay tax on our capital gains because we make a gain. Yes, its difficult handing over part of our investment success to the Tax Man for seemingly no contribution, but without success our bank balance would remain stagnant forever.

When then should you sell? In Value.able I advocate five reasons. For now I would like to share with you a possible reason. Based on any of the other reasons I may be selling Matrix so make sure you understand this is a review based on one of five reasons.

Eventually share prices catch up to value. In some cases it can take ten years, but in the case of Matrix, it has taken far less time for the share price to approach intrinsic value.

One signal to sell any share is when the share prices rise well above intrinsic value.

There are no hard and fast rules around this. And don’t believe you can come up with a winning approach with a simple ‘sell when 20% above intrinsic value’ approach either.

What you MUST do is look at the future prospects. In particular, is the intrinsic value rising? I believe it is for Matrix (and I am not the only fund manager who does – you could ask my mate Chris too).

Here’s some of his observations: Risks associated with the timing of getting Matrix’s facility at Henderson up and running are mitigated by keeping Malaga open. And Malaga is producing more units now than it was only a few months ago. Matrix could also produce more units from Henderson than they have suggested (the plant is commissioned to produce 60 units per day) and I believe the cost savings will flow through much sooner than they say. Recall the company has indicated Henderson could save circa $13 million in labour, rent and transport costs (see below analyst comment). Excess build costs are now largely spent and if the company can ramp up to 70 units a day, HY12 revenue could double.

Why do I believe this? Because a recent site visit for analysts suggested it. As one analyst told me: “Production of macrospheres has started from Henderson with 7 of the 22 tumblers in operation. This is a good example of the labour savings to come as it’s now a largely automated process – there were only 3 people working v >20 on this process at Malaga.”

(Post Script: My own visit to WA at the weekend revealed a company capable of producing just over 100 units per day – Henderson + Malaga) Moreover, the sad events unfolding in Japan will force a rethink on Nuclear. If nuclear energy – recently hailed as a green solution to global warming – reverts to being a relic of an old world order, demand for oil will increase. Oil prices will rise. Deep sea drilling will be on everyone’s radar even more so.

And the risks? Well, one is pricing pressure from competitors. This is something that needs to be discussed with management, but preferably with customers!

Some Value.able Graduates may be reluctant to place too much emphasis on future valuations. Indeed I insist on a discount to current valuations. If it is your view that future valuations should be ignored, then you should sell.

Personally I believe one of my most important contributions to the principles of value investing is the idea of future valuations. Nobody was talking about them at the time I started mentioning 2011 and 2012 Value.able valuations and rates of growth. They are important because we want to buy businesses with bright prospects. And a company whose intrinsic value is rising “at a good clip” demonstrates those bright prospects.

If you have more faith and conviction that the business will be more valuable in one, two and three years time, you may be willing to hold on. On the basis of this ONE reason I am currently not rushing to sell Matrix (of course I may sell based on any of the other four reasons), however notwithstanding a change to our view (or one of the other four criteria for selling being met) I do hope for much lower prices (buy shares like you buy groceries…)

I cannot, and will not, tell you to sell or buy Matrix and I might ‘cease coverage’ at any time. As I have said many times here, do not use my comments to buy or sell shares. Do your own research and seek and take personal professional advice.

What I do want to encourage you to do is delve deeply into the company’s history, its management, their capabilities, recent announcements and any other valuable information you can acquire.

And in the spirit demonstrated by so many Value.able Graduates, feel free to share your findings here and build the value for all investors.

When the market values a company much more highly than its performance would warrant, it is time to reconsider your investment. Looking into the prospects for a business and its intrinsic value can help making premature decisions. Premature selling can have a very costly impact on portfolio performance not only because the share price may continue rising for a long time, but also because finding another cheap A1 to replace the one you have sold, is so difficult. At all times remember that my view could change tomorrow and I may not have time to report back here so do your own research and form your own opinions. Also keep in mind that we do not bet the farm on any one stock so even if MCE were to lose money for us (and we will get a few wrong) we won’t lose a lot.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 18 March 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Have you booked your seat The SMSF Strategy Day – for charity?

Roger Montgomery

March 8, 2011

UPDATE: I spoke with Graham, editor of thesmsfreview.com.au, this afternoon. There are only a few (around ten) seats left at the event. If you would like to attend, Graham has asked me to kindly request you do so before 5pm Friday 11 March. Click here to book online.

The SMSF Review and Alan’s Eureka Report, together with my team, have gathered some of Australia’s most respected self managed superannuation and investment experts – Alan Kohler, the Cooper Review’s Jeremy Cooper, ATO Superannuation Assistant Commissioner Stuart Forsyth, Jonathan Payne and Super System Review panel member Meg Heffron, to name a few.

The SMSF Strategy Day – for charity will be held in Sydney on Tuesday, 15 March. The day begins at 8.30am with a Keynote speech from ATO Assistant Commissioner (Superannuation) Stuart Forsyth and concludes at 4pm.

I will speak at 10.30am and at 12pm will join Alan Kohler, Jonathan Payne and Jeremy Cooper for a panel discussion to debate the most popular SMSF investment strategies.

Tickets are $77 (including GST) and 100 per cent of the net proceeds will be donated to those most affected by Australia’s recent spate of natural disasters.

Click here to book your seat online.

To download the event brochure, click here.

I look forward to meeting you next week for this valuable cause.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 8 March 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

Is CSL a master of share buy backs?

Roger Montgomery

March 1, 2011

When a company buys back its shares, the announcement is often accompanied by reports suggesting either 1) the company has no other growth options towards which it can employ equity capital or, 2) the company has great confidence in its future and other shareholders should be following its lead rather than selling out to the company itself.

Back in 1984, in his Chairman’s Letter to Shareholders (a source of information I have quoted frequently here and in Value.able), Warren Buffett observed:

“When companies with outstanding businesses and comfortable financial positions find their shares selling far below intrinsic value in the marketplace, no alternative action can benefit shareholders as surely as repurchases.”

Note to CFOs and CEOs: “shares selling far below intrinsic value in the marketplace.”

It is just as important for the CEO of a public company to be buying shares only when they are below intrinsic value, as it is for Value.able Graduates building a portfolio.

Buying shares above intrinsic value will destroy value as surely as buying high and selling low – something many Australian companies became all to expert at during the GFC as they issued shares in their millions at prices not only below intrinsic value, but below equity per share.

One question to ask is if companies are engaging in buy backs today, why weren’t they when their shares were much, much lower? The answer of course may be that they may not have had the capital back then. A recovery from the lows of the GFC has not only occurred in the prices of shares trading in the market place, but also in the cash-generating performance of the underlying businesses themselves.

Irrespective of the circumstances, a company now buying back shares that had previously issued them at the depths of the GFC is having a second crack at wealth destruction.

I am pleased to report that not all companies are following the crowd. Some larger companies, including BHP, RIO and Woolworths, have announced buy backs at or slightly below my estimate of their Value.able intrinsic values.

Webjet, Customers, Coventry Group and Charter Hall Retail REIT have all announced buy backs and Bendigo/Adelaide Bank is engaging in one to reverse the impact of shares issued through their DRP.

As I wrote yesterday (Is there any value around?), value is becoming much harder to find. Companies are expensive, even my A1s. Whilst any Value.able valuation is merely an estimate, the absence of a large Margin of Safety, combined with the announcements of buy backs, does not inspire my confidence.

In the US, share buy backs historically peak at market highs. Think back to the first half of 2007 and in 1999 and 2000 – two periods that investors may have wished they’d sold shares back to the companies – are also periods during which buy backs peaked.

Share buy backs are a very public demonstration of management’s capital allocation ability, or lack thereof.

Whilst Warren Buffett is regarded as the master of share buy backs, he has often sited another capital allocator as the real genius – the late Dr. Henry Singleton, the founder and CEO of Teledyne.

When the inflation-devastated stock market of the 1970s had pushed shares to the point that some suggested ‘equities were dead’, Henry Singleton bought back so many shares that by the mid 1980s there were 90% less Teledyne shares on issue. Here’s a para from the web: “In 1976, the company attempted, for the sixth time since 1972, to buy back its stock in order to eliminate the possibility of a takeover attempt by someone eager for the cash reserves the company had accumulated. Altogether, Teledyne spent $450 million buying back its stock, leaving $12 million outstanding, compared to $37.4 million at the close of 1972. With many of the company’s divisions showing stronger results and fewer shares outstanding, Teledyne’s stock increased from a low of $9.50 per share to $45 per share, becoming the largest gainer on the New York Stock Exchange.”

Who is Teledyne’s Australian equivalent?

One iconic Aussie business (it achieves my second highest MQR – A2) immediately springs to mind. In 2009 this business issued shares at a high price to fund a $A3.5 billion acquisition. But things didn’t quite go to plan… the US Federal Trade Commission intervened and the shares slumped. What did management do? They used the cash raised from the share issue to buy them back. Amazing!

Fast-forward twelve months and this business has nearly $1 billion in cash in the bank and no debt. If it keeps using its own cash and that being generated, and buying back shares at the present rate (and assuming the share price doesn’t change of course), it will have bought back all its shares in seven years. A Value.able business… what do you think?

Yes, if not for management’s decision to buy back shares ABOVE intrinsic value.

Unfortunately CSL’s share price may not be as high in seven years as it could have been, had management chosen to buy back its shares below intrinsic value.

If you own shares in a company engaging in a buy back, ask yourself whether value is being added to the company? Value is generated when the shares being purchased are available at prices below your estimate of its Value.able intrinsic value.

If management are overpaying, inappropriate capital allocation practices may be the only addition to the future prospects of the business.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 1 March 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Health Care, Investing Education.

-

Is there any value around?

Roger Montgomery

February 28, 2011

Two themes seem to be gaining traction amongst Value.able Graduates at the moment.

1. Value is becoming harder to find (yes, I agree), and

2. Questions related to share buybacks have increased remarkably

This afternoon I will address the growing problem of finding value (and save buybacks for another day).

As I scan the market for great quality businesses trading at large discounts to my estimate of their Value.able intrinsic value, I am finding fewer and fewer opportunities. And when it comes to ‘small caps’, the prospects are few and far between.

On Peter Switzer’s show last Thursday a caller asked me what was good value in the small cap space. I define ‘small cap’ as anything between $300 million and $2 billion (below that is micro caps and nano caps). The fact is, only four or five of my highest Montgomery Quality Rated (MQR) businesses (think A1, A2, etc) are cheap. And most of them you already know about.

Forge and Matrix Composite are still below rising intrinsic values (more on those soon), and Cabcharge and ARB Corporation are just below intrinsic value. The remaining value is in much smaller companies and of course, the risk when investing in this space can be much higher.

Many Value.able Graduates have commented that investing in these micro and nano cap stocks is akin to scraping the bottom of the barrel. Whilst I tend to agree, I also believe that when it comes to investing, little is more satisfying than discovering an extraordinary business beyond the reach of the managed funds that have self-imposed restraints and must only invest in the top 200 or 300 companies.

There is merit in the concept of investing in small businesses that have the potential to become large. And there are profits to accrue when they do. Before you dismiss this idea, keep in mind that many of the large companies dominating Australia’s competitive landscape today were once small. Admittedly, in many cases they were small while they were buried in private ownership or private equity ownership, but in some examples they were small and grew to be large whilst they were listed. Can you think of a few examples? The Value.able community has shared a few here at my blog.

Given Australia’s small population, the big businesses that dominate the investment landscape are mature and have to make smart decisions and continually reinvent themselves to continue to grow. Think about Harvey Norman. Its failing is not in the fact that the economy is slow or that consumers can buy cheaper goods overseas. Its failing is that it is a tired old concept that has lost its mojo. The company has failed to change and failed to reinvent itself. Its own failure has seen it fall victim to the JB Hi-Fi’s and the buy-online-from-overseas-cheaper.com merchants of the world.

So whilst scouring for smaller companies may seem like bottom-fishing, there is merit in catching the smaller fish. And for those investors who prefer to stay clear, patience, bank bills and term deposits are the solution.

Far better is it to be in the safety of cash than in inferior investments, such as companies trading at premiums to intrinsic value.

Forewarned is forearmed. And to be forewarned, don’t miss out on your copy of Value.able. As I told Peter last week, there aren’t too many Second Edition copies left.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, author and fund manager, 28 February 2011.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education.