Consumer discretionary

-

JB Hi-Fi Full Year Results for 2012

Roger Montgomery

August 13, 2012

JB Hi Fi today reported its full year results. Revenue of $3.13b was 6% higher than FY11, but NPAT was down 4.6% to $104.6m. While this was the first decline in JB Hi-Fi NPAT since it listed in 2003, it was slightly better than the market had anticipated and, as I write, the share price is up over 6%.

As value investors, we are more concerned about the long-term than the intra-day outlook, and the question exercising our minds is: to what extent are the current headwinds cyclical vs. structural?

JB Hi-Fi believes that most of what is happening is cyclical, and there is some evidence that can be marshaled to support that view. However, it can also be said that retailers who previously competed locally must now compete with the best in the world. In this context, retailers that must pay Australian prices for rent, staff and utilities have some relatively big hurdles to clear.

Investors should also be aware of two interesting financial developments. Looking at the Profit & Loss statement you will see EPS has risen from 101.76 cents to 105.93 cents.

But the charts of EPS in the remuneration section reveal a very different picture. You see, the P&L includes an abnormal loss of $33 million associated with the Clive Anthony’s ‘restructure’. Take the abnormal loss out and the continuing operations made EPS of $1.247 in 2011 against this year’s $1.059. If it was ok to use $1.247 for the execs in working out their incentives, it should be ok for shareholders to use to compare this year’s P&L!

And for those investors enamoured with cash flows, don’t get too excited by the cash flow from operations jumping to more than $215 million from $105 million last year. You see, there’s been a $100 million blow out in payables. In other words JBH appears to have held off paying its suppliers a little longer.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary.

-

Deflation of fresh produce masks volume growth from Woolies and Coles

Roger Montgomery

July 31, 2012

The Woolworths Food and Liquor Division reported 3.8% sales growth to $37.5 billion for the year to June 2012. Same store sales growth increased by 1.3% for the year. For the June Quarter, sales growth was 3.8%, year on year, while same stores sales grew by 1.3%.

In comparison, Coles reported sales growth of 6.1% to $33.7b and same store sales growth of 3.7%. For the June Quarter, sales growth was 4.6%, year on year, while same store sales grew by 3.0%.

Both organisations reported price deflation of approximately 4% in fresh produce, and this masked both their strong volume growth and the increasing consolidation of the Australian supermarket industry.

The Montgomery (Private) Fund is a shareholder in Woolworths, and likes its 26% average return on equity.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Insightful Insights.

-

Is this a Thorny Investment?

Roger Montgomery

June 24, 2012

We all know that retailing is doing it tough and there’s hardly bright lights on the horizon. (Of course it is always darkest just before the dawn but our experience is telling us that most analysts are scraping the bottom of the barrel for opportunities when scrounging around trying to pick up scraps of returns from post announcement arbitrage opportunities. Conversely, the frequency of observations in this space suggests those with plenty of spare cash reckon we are close to the bottom).

We all know that retailing is doing it tough and there’s hardly bright lights on the horizon. (Of course it is always darkest just before the dawn but our experience is telling us that most analysts are scraping the bottom of the barrel for opportunities when scrounging around trying to pick up scraps of returns from post announcement arbitrage opportunities. Conversely, the frequency of observations in this space suggests those with plenty of spare cash reckon we are close to the bottom).One business that also happens to be a retailer (as measured by current business unit revenues) and one we have previously owned is Thorn Group but its outperformance of the retail sector is unlikely to be sustained unless its investment in new products pays off.

(NB. Later in the week I will seek permission to give you some School Holiday reading – Michael’s 20-page Magnum Opus on TGA)

The picture at left should really be of the Tortoise from Aesop’s fable The Tortoise and The Hare. You will see why shortly…

It goes without saying that Australian retailers are doing it tough. But just how tough? Compare the share price performance of some household names in retail to the performance of the All Ordinaries index over the past 12 and 24 months.

The high Australian dollar, record outbound tourism, high petrol prices, rising utility costs, indebtedness, a slowing economy, cautious consumers and a structural shift rendering bricks-and-mortar retailers less competitive have seen earnings downgrades come in thick and fast amongst retailers. As well as being tough on the businesses and their managers, retailing has also been a tough place to be an investor.

But one company appears to be bucking the trend, in business terms; that company is Thorn Group (TGA). While the past 12 months have proven just as difficult for the company’s share price as they have for its contemporaries (perhaps not pure peers), it’s the 24-month performance of this business that sets it apart. And if a business does well, the shares usually follow.

Many retailers have seen their share prices decline 40-50%, yet Thorn has delivered an impressive two-year return to shareholders.

Better still, the business continues to do well. In its latest annual report, released last week, Thorn Group reported NPAT up 26.4% (EPS was up 14% post capital raising). A retailer whose bottom line is actually growing is rare in the current environment; compare Thorn with forecasts for JB Hi-Fi (JBH), Harvey Norman (HVN), Myer (MYR) and David Jones (DJS) in 2012.

Tomorrow’s returns to shareholders however will be dependent on how the business performs in the future. So the question, of course, is whether this outperformance is sustainable? I always look for businesses with ‘bright prospects’.

A quick look under the hood reveals Thorn’s Revenue (first column each year) and EBIT (second column each year) breakdown. The key to the group’s prospects – even after the recent acquisition of NCML, which contributed 20% of EBIT growth – is the rental segment, which represents 92.5% of EBIT. It’s also identified by management as the company’s ‘core’ operations.

Clearly, given its contribution to the bottom line, it is the rental segment (not Cash First, Equipment Finance or NCML) that will help identify whether or not the business’ prospects are good. We appreciate that the other segments will/may grow but the company’s slow and steady organic approach to growth will ensure it is the prospects for the Rental/Retail business that determine investor returns in the foreseeable future). In this segment, we find Radio Rentals and Rentlo.

‘Consumer rental operations’ would be an apt description for this segment, which is responsible for the retailing of browngoods, whitegoods, PCs, furniture products and other goods such as gym equipment. The revenue breakdown by product and change in product mix is estimated as follows.

The ‘change’ column raises an eyebrow for me. Over the last two to three years, the rental segment of Thorn has experienced very strong customer growth, driven in the main by its $1 ‘Rent-Try-Buy’ promotion. High single-digit growth rates have been produced across the board.

Recently, however, this rate has fallen to the low single-digit rate of 3.1%, and as can be seen in four out of five product groups, growth is negative, flat or marginal. The hero in the product mix, however, is clearly furniture but in my observation, heroes eventually come unstuck.

I reckon the growth in furniture highlights the fact that consumers tend to ‘rent’ higher ticket items. Deflation in electronics means that the decision to buy over renting is a far less taxing one. The result is more people buying the laptop and LED TV versus renting. Indeed, much has changed in retailing because that which was once aspirational is now disposable. I like that phrase and have now trademarked it!

Couple the low rates of growth with customer churn and an increase in impairment charges on the rental book and we have a stronger case building for a period of muted to possibly negative growth. This is only offset if the company’s aim to extend furniture to outdoor product ranges and extend to new brands (eg Apple) works sufficiently.

According to a recent company presentation, 44% of customers are retained when their old rental agreement matures. That is to say, these customers purchase another product under another contract. This implies that about 56% of all customers will drop off once their first purchase is fully paid. Whether the 44% that remain are upsold and the rate that they are replaced, determines the rate of growth.

In strong growth years, churn is easily offset by more customers entering the business than leaving. And given the strong growth in customers over the past few years, this has been the case.

But when growth rates fall – a sign of a tighter marketplace, changing consumer trends and a potential maturing business (remembering that Thorn grew strongly during the GFC) – churn becomes harder and harder to fight, and the status quo tougher and tougher, as well as more expensive, to maintain.

With an average 27-month contract term, and given strong growth from 2009 onwards, from here the business will likely experience a larger proportion of their 100,000 customer rental agreements coming to term and maturing. Prior comparative period (PCP) comparisons could look less attractive.

Unless that retention rate can be materially lifted, new customers coming in must continue to exceed customers exiting. With the trend into 2013 on the up, the outcome here is likely to be a much tougher battle and flat to slightly negative growth in the core business, which generates in excess of 90% of EBIT.

The key question, therefore, becomes: how long will it take for the investment in new products – Cash First, Equipment Finance and Kiosks – to begin paying off? This will be the next leg in business performance and if that occurs, the share price will, of course, eventually follow.

Thorn is a well-managed business and has a strong balance sheet, cash flow and management, with a track record of delivering new revenue streams through differentiated business models that, with the exception of the NCML acquisition pimple, has been organic. But until those new models begin to gain traction, on my analysis it looks as though the business has a tougher couple of years ahead of it.

Before I head off on holidays I will provide a link to Michael’s Magnum Opus (POST SCRIPT: SEE MICHAEL’S 20-PAGE SPECIAL IN THE COMMENTS BELOW) on TGA where he agrees generally with this conclusion stating:

“I think that Thorn’s growth will slow for 2013, do better in 2014, then experience an up-tick as initiatives like Cashfirst, Thorn Equipment Finance and individual expansion initiatives in Radio Rentals/Rentlo and NCML move from making losses, or small profits, to being acceptably profitable. EPS will grow, but nothing like the EPS CAGR of the last five years.”

And while outperformance over the rest of the retail sector has likely to come to end, the company is one I plan to keep a close eye on.

First Published May 2012. Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author, Skaffold Chairman and Fund Manager, 24 June 2012.

To pre-register for the soon-to-be-released Montgomery retail fund visit www.montinvest.com and click the APPLY TO INVEST button. A Pre-Registration Form will appear and after completing it, be sure to select the button “Retail Investor < $500,000″. You will then receive an automated email from my office and be registered to receive the PDS/FSG and Information Booklet as soon as it’s received all of its approvals. If you decide to proceed and/or your advisor does, we look forward to working for you. If you are a planner or advisor or responsible for dealer group approved lists or you are an executive at a research house or ratings agency and would like to discuss next steps feel free to call the Mr David Buckland at the office on (02) 9692 5700. Investments can only be made through the PDS and a Financial Services Guide (‘FSG’) will also be available.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Consumer discretionary.

-

Has Wesfarmers got it right?

Roger Montgomery

May 28, 2012

In writing Value.able I wanted to explain return on equity almost as much as I wanted to introduce the idea of future intrinsic value estimates and Walter’s intrinsic value formula.

In writing Value.able I wanted to explain return on equity almost as much as I wanted to introduce the idea of future intrinsic value estimates and Walter’s intrinsic value formula.From Value.able, PART TWO, The ABC of Return on Equity:

Return on equity is essential for value investors for so many reasons and Wesfarmers purchase of Coles was a great case study:

“In 2007, Wesfarmers had Coles in its sights. In that same year, Coles reported a profit of about $700 million. In its balance sheet from the same year, Coles reported about $3.6 billion of equity in 2006 and $3.9 billion of equity at the end of 2007. For the purposes of this assessment we will accept that the assets are fairly represented in the balance sheet. Using only these numbers we can estimate that the return on average equity of Coles was around 19.9 per cent.

Importantly, Coles has been around a long time, is stable, very mature and established and supplies daily essentials. While its prospects may not be exciting, there is the possibility that Wesfarmers may improve the performance of the Coles business.

So the target, Coles, is a business with modest debt and $3.9 billion of good-quality equity on the balance sheet that generated a 19.9% return. The simple question is: What should Wesfarmers pay for Coles? If it gets a bargain, it will add value for the shareholders of their business. If it pays too much, it will do the opposite – destroy value and perhaps its reputation.

Now, if you were to ask me what to pay for $3.9 billion of equity earning 19.9 per cent (assume I can extract some improvements), I would start by asking myself what return I wanted. If I were to demand a 19.9 per cent return on my money, I would have to limit myself to paying no more than $3.9 billion. If I was happy with half the return, I could pay twice as much. In other words, if I was happy with a 10 per cent return, which I think is reasonable, I could pay $7.8 billion, or two dollars for every dollar of equity. And finally, if I think that I could do a much better job than present management, I could pay a little more, $9.75 billion perhaps.

Now suppose you consider yourself much better at running Coles than the present Coles management. Remember, this is one of the motivators for acquisitions. Suppose you believe that you can achieve a sustainable 30 per cent return on equity. Assume you were seeking a 10 per cent return on your investment – a modest return by the way, but justified by the risks involved.

The basic formula to calculate what you should pay for a mature business, like Coles, is:

Return on Equity/Required Return x Equity

Using this formula the estimated value of Coles is:

0.3/0.1 x 3.9 = $11.7 billionEven if I thought I was a brilliant retailer, I would not want to pay more than $11.7 billion for Coles. Given the risks, I may want a higher required return than 10 per cent. If I demanded a 12 per cent required return, I would not pay more than $9.75 billion (0.3/0.12 x 3.9 = $9.75).

I will explain this formula, which represents the work of Buffett, Richard Simmons and Walter in more detail in Chapter 11 on intrinsic value.

Of course, if we think that the balance sheet is overstating the value of the assets, the result would be a lower equity component and a higher return on equity. As Buffett stated:

Two people looking at the same set of facts, moreover – and this would apply even to Charlie and me – will almost inevitably come up with at least slightly different intrinsic value figures.

The result will be modestly different but the conclusion will be the same.

With around 1.193 billion shares on issue, the above estimates suggest Coles might have been worth between $8.17 and $9.80 per share.

Now, what did Wesfarmers announce they would pay for Coles? The equivalent of about $17 per share!

What do you think would happen to your return on equity if you paid the announced $22 billion for a bank account with $3.9 billion deposited earning 19.9 per cent? Your return on equity would decline precipitously to around 3.5%.”

With that in mind I wonder whether the comments Wesfarmers were reported today to have made to The Financial Review (see image, I subscribe and think its great) were complete. Of particular interest is the paragraph; “The way we create value to shareholders is to increase return on capital. There’s no doubt when we bought Coles we bought a very big business with very low return on equity and that reduced the return on equity for the company.”

Assuming the comments and statistics are correct, I would argue that the reason for the decline in Wesfarmer’s Return on Equity is not because Coles had a low ROE – as Wesfarmers are reported to have suggested – but because Wesfarmers simply paid too much for Coles. Do you agree or disagree?

What are your thoughts?

Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author, Skaffold Chairman and Fund Manager, 28 May 2012.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Skaffold, Value.able.

-

My…Err?

Roger Montgomery

May 27, 2012

Investors don’t have to have astronomic IQ’s and be able to dissect the entrails of a million microcap startups to do well. You only need to be able to avoid the disasters.

In an oft-quoted statistic, after you lose 50% of your funds, you have to make 100% return on the remaining capital just to get back to break even. This is the simple reasoning behind Buffett’s two rules of investing. Rule number 1 don’t lose money (a reference to permanent capital impairment) and Rule Number 2) Don’t forget rule number 1! Its also the premise behind the reason why built Skaffold.

Avoiding those companies that will permanently impair your wealth either by a) sticking to high quality, b) avoiding low quality or c) getting out when the facts change, can help ensure your portfolio is protected. Forget the mantra of “high yielding businesses that pay fully franked yields” – there’s no such thing. That’s a marketing gimmic used by some managers and advisers to attract that bulging cohort of the population – the baby boomers – who are retiring en masse and seeking income.

Think about it; How many businesses owners would speak about their business in those terms? “Hi my name is Dave. I own an online condiments aggregator – ‘its a high yielding business that pays a fully franked yield’. You will NEVER hear that from a business owner. That only comes from the stock market and from those who have never owned or run a business.

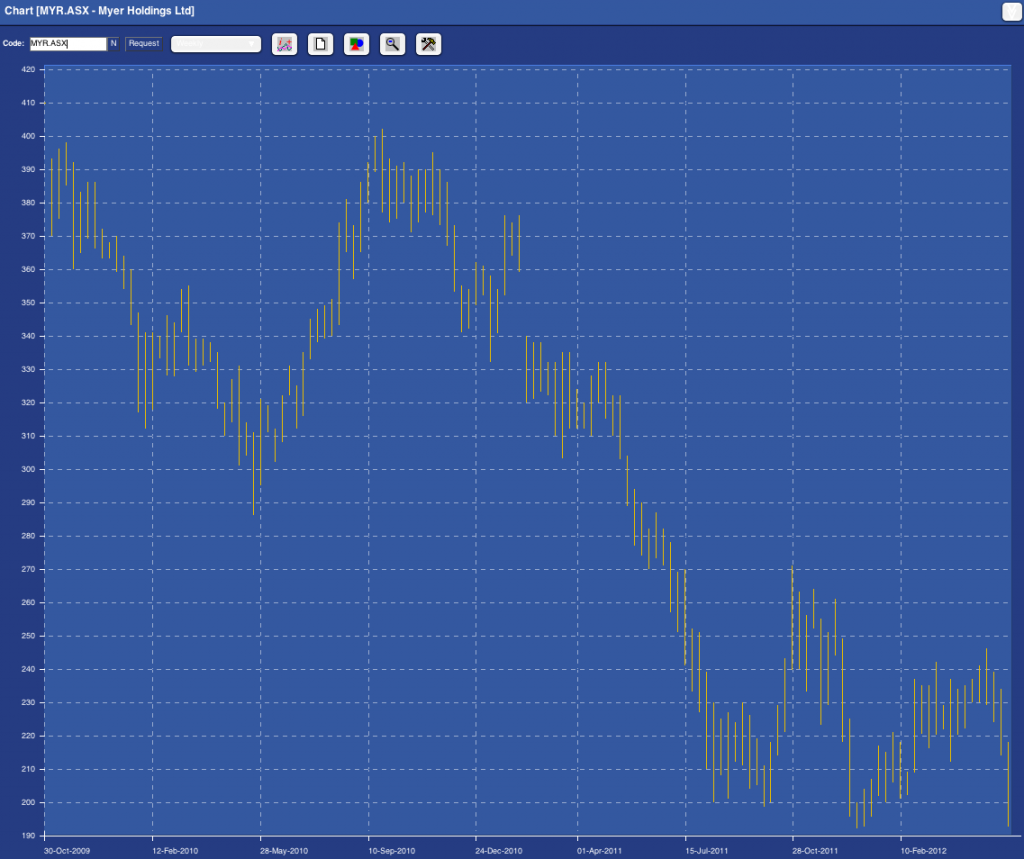

They key is not to think about stocks or talk stock jargon. Just focus on the business. Thats what we did when Myer floated in 2009. And with the market value of Myer now 50% lower than the heady days of its float, it might be instructive to revisit the column I wrote back on 30 September 2009, when I reviewed the Myer Float.

And sure, you can say that the slump in retail is the reason for the slump in the share price of Myer (I am certainy one who believes that the dearth of really high quality companies means multi billion dollar fund managers are bereft of choice meaning that a recovery in the market will make all stocks rise – not because they are worth more but because fund managers have nothing else to buy). But the whole point of value investing is to make the purchase price so cheap that even if the worst case scenario transpires, you are left with an attractive return.

It would be equally instructive to review the reason why we didn’t buy the things that subsequently went well (QRN comes to mind) so we’ll leave that for a later date.

Here’s the column from September 2009:

“PORTFOLIO POINT: The enthusiasm surrounding the Myer float is good reason for a value investor to stay clear. So is the expected price.

With more than 140,000 investors registering for the IPO prospectus, everyone wants to know whether the float of the Myer department store group will be attractive. This week I want to focus exclusively on this historic offer.

At present it is suggested the stock will begin trading somewhere between $3.90 and $4.90.

The prospect of a stag profit draws a self-fulfilling crowd. But if chasing stag profits is your game, I would rather be your broker than your business partner, for history is littered with the remains of the enthusiasm surrounding popular large floats.

Popularity, you see, is not the investment bedfellow of a bargain and being interested in stocks when everyone else is does not lead to great returns. You cannot expect to buy what is popular, travel in the same direction as lemmings and generate extraordinary results. Conversely thumb-sucking produces equally unattractive returns.

Faced with these truisms, I lever my Myer One card, obtain a prospectus and open it for you.

The Myer float is one of the hottest of the year and I am not referring to the cover adorned by Jennifer Hawkins! If those 146,000 people who have apparently registered for a Myer prospectus were to invest just $20,000 at the requested price, the vendors will have their $2.8 billion plus the $100 million in float fees in the bag.

A word about the analysis: It is the same analysis I have used to buy The Reject Shop at $2.40 (today’s close $13.35), JB Hi-Fi at $8 ($19.86), Fleetwood at $3.50 ($8.75), to sell my Platinum Asset Management shares at more than $8 on the morning they listed (at $5), and to warn investors to get out of ABC Learning at $8 (they were 54¢ when ABC delisted in August 2008) and Eureka Report subscribers to get out of Wesfarmers as it acquired Coles.

I don’t list these to boast but merely to demonstrate the efficacy of the analysis; analysis that is equally applicable to existing issues and new ones.

By way of background, TPG/Newbridge and the Myer Family acquired Myer for $1.4 billion three years ago. They copped flack for paying too much, but “only” used $400 million of their own capital; the remainder was debt. Before the first anniversary, the Bourke Street, Melbourne, store was sold for $600 million and a clearance sale reduced inventory and netted $160 million. The excess cash allowed the new owners to reduce debt, pay a dividend of almost $200 million and a capital return of $360 million. Within a year the owners had recouped their capital and obtained a free ride on a business with $3 billion of revenue. Good work and smart.

But I am not being invited to pay $1.4 billion, which was 8.5 times EBIT. I am being asked to pay up to $2.9 billion, or more than 11 times forecast EBIT. And given the free “carry”, the bulk of the money raised will go to the vendors while I replace them as owners. Ownership is a very good incentive to drive the performance of individuals.

And driven they have been. In three years, $400 million has been spent on supply chain and IT improvements, eight distribution centres have been reduced to four and supply-chain costs have fallen 45%. Amid relatively stable gross profit margins, EBIT margins improvement to 7.2% and a forecast 7.8% reflect disciplined cost identification and management. Fifteen more stores are planned for the next five years and the prospectus notes that trading performance improved significantly in the second half of 2009 and into the first half of 2010. The key individuals have indeed performed impressively, but with less skin in the game they may not be incentivised as owners in future years as they have been in the past.

And what value have all these improvements created? The vendors would like to believe about $1.4 billion, and if the market is willing to pay them that price, they will have been vindicated, but price is not value and I am interested simply in buying things for less than what they are worth.

In estimating an intrinsic value for Myer, I will leave aside the fact that the balance sheet contains $350 million of purchased goodwill and $128 million of capitalised software costs. This latter item is allowed by accounting standards but results in accounts that don’t reflect economic reality. Historical pre-tax profits have thus been inflated.

I will also leave aside the fact that the 2009 numbers and 2010 forecasts have also been impacted by a number of adjustments, including the addition of sales made by concession operators “to provide a more appropriate reference when assessing profitability measures relative to sales”; the removal of the incentive payments to retain key staff – not regarded as ongoing costs to the business; costs associated with the gifting of shares to employees; and, most interestingly, the reversal of a write-off of $21 million in capitalised interest costs – all regarded as non-recurring.

Taking a net profit after tax figure for 2010 of $160 million and assuming a 75% fully franked payout, we arrive at an owners’ return on equity of about 28% on the stated equity of $738 million, equity that could have been higher after the float if $94 million in cash wasn’t also being taken out of retained profits. Using a 13% required return, I get a valuation of $2.90.

Looking at it another, albeit simplistic way, I am buying $738 million of equity that is generating 28%. If I pay the requested $2.9 billion for that equity or 3.9 times, I have to divide the return on equity by 3.9 times, which produces a simple return on “my” equity of 7.2%. For my money, it’s just not high enough for the risk of being in business.

Importantly, the return on equity – based on the simple assumptions that three stores, each generating $40 million in sales will be opened annually over the next five years and that borrowings will decline by $60 million in each of those years – should be maintained. But the end result is that the valuation only rises by 6% per year over the next five years and delivers a value in 2015 of $3.90: the price being asked today.

My piece of Myer seems a bit hot for My money.”

That was 2009. Has anything really changed? Has the following chart reveals. Myer is now trading at close to Skaffold’s current estimate of its intrinsic value. Before you get too excited (although the shortage of large listed high quality retailers means even this company’s shares may go up in a market or economy recovery) take a look at the pattern of intrinsic values in the past and the currently anticipated path of forecast intrinsic values; Past intrinsic values have been declining (generally undesirable unless forecasts for a recovery are correct) and forecast intrinsic values are flat.

Fig.1. Skaffold Myer Intrinsic Value Line

And as the Capital History chart reveals, 2014 profits are not expected to be better than 2010. That 4 years without profit growth. Question: Would you buy an unlisted business (as a going concern) that was not forecasting profit growth for four years?

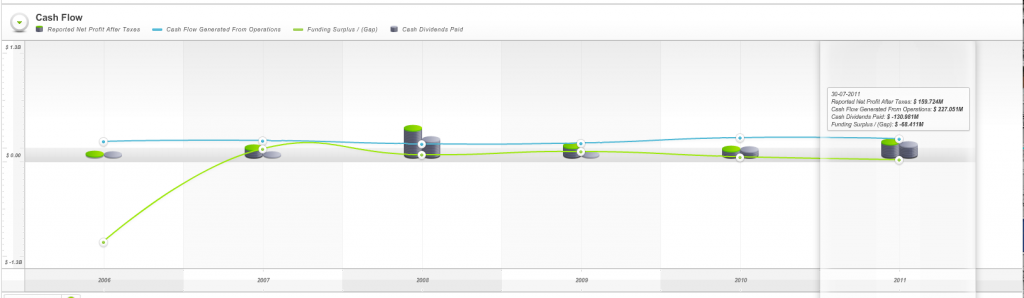

Fig. 2. Skaffold Myer Capital History Chart

Finally the cash flow chart reveals the company has produced what Skaffold refers to as a Funding Gap. Its cash from operations have not been enough to cover the investments it has made in others or itself plus the dividends it has paid. In other words for 2010 and 2011, the two financial years it has registered as a listed company, it appears from Skaffold’s data that the company has had to dip into either 1) its own bank account, or 2) borrow more money or 3) raise capital (the three sources of funds available if a funding gap is produced) to cover this “gap”.

Fig. 3. Skaffold Myer Cash Flow Chart

I’d be interested to know if you are a loyal Myer shopper or not and why? If you don’t shop at Myer, why not? If you do shop at Myer, what do you like about the company, its stores and the experience? And I am particularly interested to hear from anyone who DOES NOT shop there but DOES own the stock!

Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author, Skaffold Chairman and Fund Manager, 27 May 2012.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Value.able.

-

Should you watch director’s dealings?

Roger Montgomery

May 8, 2012

Once upon a time JB Hi-Fi was a category killer: its returns on equity were unassisted by debt and stratospheric and it was all reflected in a strong share price. But something has changed. I wrote previously, and commented elsewhere, that JB Hi-Fi was maturing, that returns on equity were flattening and that the sun was setting on the ability of the business to reinvest profits at the very high returns of the past. The impact of this of course is flatlining intrinsic values. Indeed take a look at the Skaffold valuation line chart below. You can see that even by 2014, JBH’s intrinsic values are expected to show no appreciation from 2009/2010. Maturity.

Once upon a time JB Hi-Fi was a category killer: its returns on equity were unassisted by debt and stratospheric and it was all reflected in a strong share price. But something has changed. I wrote previously, and commented elsewhere, that JB Hi-Fi was maturing, that returns on equity were flattening and that the sun was setting on the ability of the business to reinvest profits at the very high returns of the past. The impact of this of course is flatlining intrinsic values. Indeed take a look at the Skaffold valuation line chart below. You can see that even by 2014, JBH’s intrinsic values are expected to show no appreciation from 2009/2010. Maturity.That of course hasn’t prevented me from buying a few shares around$15.00. Fortunately however we were quick to change our mind and even secured a small profit.

I wonder whether the first signs of business performance beginning to mature, is often the point when it becomes worth watching what directors do with their shares for some further insights?

JB Hi-Fi’s CEO, Richard Uechtritz, had been at the company for a decade prior to his retirement in 2010 and those watching his share dealings may have drawn a different conclusion to those being lulled by a bullish share price.

At the outset let me say there is no impropriety in a director selling their shares and none is suggested here. Directors are free to sell shares within the bounds of their staff trading policy and are required to report their dealings to the market.

And it’s through these announcements that the investor can see what directors are doing with their shares.

On August 20, 2009, JB Hi-Fi’s CEO held 2 million shares and 627,000 options

and he exercised options to buy another 180,048 shares at $7.27. A week later, JB Hi-Fi’s CEO had sold all of shares he had just purchased the week before for an average price of $17.65.

Then, between September 2 and 3, 2009, another 500,000 shares were sold at an average price of $18.22. By now JB Hi-Fi’s CEO held 1.5 million shares (down from 2 million on AUgust 20) and 447,267 options (down from 627,000).

Skaffold’s Valuation Line Evaluate screen for JBH reveals a maturing intrinsic value – little growth and lower IV in 2014 than 2010.

To alleviate the need to read thousands of annual reports, for every listed company, going back a decade try www.skaffold.com

Now back to our regular programming…

Between August 20 and September 3, there are just 13 days – call it two weeks.

Another 174,656 options were granted on 14 October 2009, and then, in early February 2010, JB Hi-Fi announced the retirement of its CEO.. Having sold 680,048 shares in the seven months before the announcement, JB Hi-Fi’s CEO sold another 500,000 shares during the first five days of March 2010 at an average price of $19.74 leaving him with 1 million shares and 621,923 options.

In his final director’s interest notice in May 2010, the retiring CEO of JB Hi-Fi listed his direct equity interest in the company at 1 million shares and the 621,923 options. For investors who are interested in gaining a possible inside track on the prospects and potential of a business, it may be useful to watch directors’ dealings in their shares.

Of course sometimes the selling can mean nothing at all but my observation is that watching the selling offers some insights. If motivated by urgency, a desire to lock in lofty share prices or grim expectations, information about director’s selling can be more useful than watching their buying.

In April 2011 (about a year later), Richard Uechtritz returned to JB Hi-Fi as a Non-executive director. Until his return, he didn’t have director’s obligations so he was not obliged to make public any of his private share dealings. Upon his return, however, he revealed that he owned only 421,000 options. In other words, he appears to have subsequently sold the one million shares he held at the time of his retirement.

JB Hi-Fi shares do not enjoy the lofty levels they once commanded and investors who tracked the sale of shares by its CEO may have been given a prompt to look deeper into the company, its prospects or at least the impact of those prospects on its shares. Of course it could all be happenstance, company CEO’s have no particular insights and their selling is purely a reflection of the need to diversify. ANy subsequent share price declines may just be coincidental.

JB Hi-Fi’s latest results were less than spectacular and, while the company will continue to win in the race against its listed peers, the reality is its margins remain under increasing pressure, it’s losing share to the internet and its remaining store rollout plan is contributing to a maturing set of metrics. Oh, and the share price now? Just above $9.30.

So do you think you should keep an eye on director’s dealings? What have been your observations? Can you nominate some companies in which directors dealings having given you cause to pause…

Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author, SkaffoldChairman and Fund Manager, 9 May 2012.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Consumer discretionary, Skaffold, Value.able.

-

MEDIA

Harvey Norman is down, but will it rise again?

Roger Montgomery

May 4, 2012

A 7% slump in sales for the first 3 quarters of 2012 has taken a predictable toll on the Harvey Norman share price – but will things turn around when the economy improves? Roger Montgomery discusses his views in this Sydney Morning Herald article published on 4 May 2012. Read here.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, In the Press.

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Consumer discretionary, In the Press

-

Can JBH get its Mojo back?

Roger Montgomery

April 27, 2012

What a difference a high Australian dollar (lots of people travelling and spending their money overseas and not here), a shift to online retailing, deflation, competitors going out of business, higher petrol prices and a more cautious consumer can make in the retail space in just nine months. And few companies are more exposed to all these influences than JB Hi-Fi.

Back in August 2011, the company reported the following in their annual report;

FY11 Sales $2.96b

FY11 NPAT $134.4m

FY11 NPAT Margin 4.5%

Based on these numbers as well as company guidance for sales growth in FY12 of 8% to $3.2b, the consensus analyst view at the time was for 11% FY12 NPAT growth to $150m.

Since that time however, shareholders have suffered three profit downgrades – in mid December, mid February and another this morning.

In this morning’s trading update, management have guided analysts to an estimated NPAT of $100-$105m on sales of $3.1b. Based on this latest announcement, 2012 numbers will look like this (assuming no further downgrades);

FY12 Sales $3.10b

FY12 NPAT $102.5m

FY12 NPAT Margin 3.3%

What’s clear from these numbers is that sales revenue is growing. No immediate issues there. And despite being below the initial 8% forecast, sales are now forecast to grow by 5%. The concern however is that LFL (like-for-like) sales are negative. For the nine months, sales of mature (older established stores) are down 1.3% which means without their current expansion plans, sales targets would not be met. It’s also the main reason their initial 8% sales growth target won’t be met.

But the main issue in forecasting what the business is worth is that despite this incremental sales growth, this is not CURRENTLY being converted to the bottom line. Based on management’s forecasts, NPAT margins will be 3.3% this year vs. 4.5% in the year prior, a 26.7% margin decline in just nine months. No businesses can increase intrinsic value in such an environment.

The tide that’s currently running against JBH is very strong, no plaudits for pointing that out. But when that tide turns, could JB Hi Fi be in an even better position than it was going into the non-resource-recession (a.k.a. the seven cylinder recession of 2012). There’s certainly the possibility and the key is working out when the economy turns and whether the structural changes occurring in retail are enough to adversely impact and offset the benefits of a cyclical turnaround.

Here’s what we are watching:

· Recently management including CEO Terry Smart and Chairman Patrick Elliot have been heavy sellers of their own personal holdings in JBH. What do they know? Why are they selling?

· The retail industry is experiencing a huge shake-up. Many retailers are doing it tough and many more are exciting the space. The Good Guys was being shopped around for a private sale recently with Blackstone rumoured to be the suitor. Later denied by them. Clive Peters (now owned by JBH) and WOW Sight and Sound have gone into receivership and JB’s largest competitor Dick Smith (owned by Woolies) is set to close 100 stores by 2014. Few electronic retailser are investing in growth. The night is darkest just before the dawn so we are looking for evidence that JB Hi Fi is capturing market share in such an environment, either by making acquisitions of distressed sub-scale business or by taking over leases in locations previously unavailable to them. In QLD it appears up to $250m in sales are up for grabs as competitors close. Dick Smiths had $1.5b in sales of which an optimistic analyst would say that JBH could pick up a substantial portion of.

· Currently electronic retailers are on the back foot evidenced by store closures and liquidation sales. These participants are forced sellers of excess stock putting HUGE downward pressure on retail prices and hence profit margins. In March alone, JBH experienced a 200 bps contraction in gross margins. I was silly enough to buy two C3-PO USB keys for my kids at Christmas for $40 each but picked up another two in Brisbane a few weeks ago for $18 at a closing down Dick Smiths (my new book will be called How to Go Broke Saving MoneyTM).

Margin compression of the magnitude reported recently is unprecedented for an operator of JBH’s buying power. So we are looking for signs that the worst is over in terms of competitors closing their doors, a sure sign margins will improve or cease falling precipitously.

· We are also watching closely JBH’s move into the online space. Growth has been excellent in this segment of the business (admittedly off a low base) with an average of 965,000 website visitors each week. That’s 50.2m views per annum – 2.4 times the population of Australia. The trick of course is to convert page views to sales.

· In prior years the business has benefited immensely from positive LFL sales and also an internally funded store-rollout strategy driving new sales and sales as stores matured. This was a tailwind for the business when the number of new stores being added divided by existing stores produced a high ratio. For example when the business only had 50 stores and another 15 were opened, the proportion of stores growing and adding to sales was 30%. At present the business has in excess of 150 stores and is opening 14-15 stores per annum – a ratio of just 10% in new growth. So when you have negative LFL sales in existing and maturing stores, this is a huge drag on business momentum. We are therefore watching for signs that LFL sales stabilise or turn positive so that the business gets its mojo back.

We think it can although we are convinced the very easy money from the store roll out stage of the business along with P/E expansion has been made. Businesses with a leading market position are able to survive traumatic periods in what is a highly cyclical business and are able to absorb the effects of margin compression. Provided they can capture high levels of market share amid the tumult and cement their position as the dominant player JBH might be well positioned for the next economic recovery. One might ask whether ‘Terry and Co’ will be there when that happens.

Skaffold.com Intrinsic Value 13 year chart.

Skaffold’s conservative valuation estimate for JBH is $13.43 for 2013 as can be seen by the thin orange line in the above chart. Whether the share price now approaches that valuation or that valuation instead is revised lower and approaches the price will be determined by whether the company can harness its opportunity and when the irrational pricing associated with collapsing competitors ends. Of course after that, its success will be dependent on the depth of the impact of the structural change represented by the retail shift global and online.

Amid all of your bearishness about housing in Australia, do you think retailing conditions will pick up for JBH and its peers or not? Can you buy goods that JBH sells cheaper online?

Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author, SkaffoldChairman and Fund Manager, 27 April 2012.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Consumer discretionary, Skaffold.

-

MEDIA

Can Apple’s share price continue to climb?

Roger Montgomery

April 3, 2012

Roger Montgomery discusses with Ticky Fullerton on ABC1’s ‘The Business’ how the ever-increasing climb of Apple’s share price is likely to come under pressure. Watch here.

This edition of The Business was broadcast 4 April 2012.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Consumer discretionary, Energy / Resources, Intrinsic Value, Investing Education, TV Appearances.

-

Are the pizzas better at Dominos?

Roger Montgomery

March 27, 2012

PORTFOLIO POINT: Despite the headwinds facing retailers in Australia, Domino’s Pizza is growing and expanding its margins. But is that growth already be priced in?

PORTFOLIO POINT: Despite the headwinds facing retailers in Australia, Domino’s Pizza is growing and expanding its margins. But is that growth already be priced in?Retailers in Australia are facing a perfect storm of weak consumer spending, online competition and a rising Australian dollar. But despite these headwinds, there’s one company that is not only expanding its physical footprint, but is becoming a serious force online. It’s also notching up double-digit growth in Europe, in spite of the economic climate, and breaking records to boot. You may be surprised to learn that this success story is in fact Domino’s Pizza Enterprises (ASX: DMP).

Domino’s Pizza listed on the Australian stock exchange in May 2005, and opened its 400th store in the same year. The company is the largest pizza chain in Australia and enjoys a growing presence in France – a country that, with the exception of the United States, consumes more pizza per head than anywhere else in the world – Belgium and the Netherlands, having bought existing operations in those countries in 2006 and becoming the largest Domino’s franchisee in the world. Domino’s Pizza now operates more than 889 stores, employs more than 16,500 people and, according to one report, makes more than 60 million pizzas per year. And all of this is run by a Lamborghini-driving CEO, who is as obsessed about Domino’s today as he was when he merged his 17-store franchise company into what is now Domino’s Pizza Enterprises.

The company’s online strategy has been a raging success, not only for pizza ordering but also for recruitment. When the company launched its iPhone App in 2009, it became the number one free app on the iTunes site within five days. Today, 40% of orders are made online and the company expects this to be 50% in the next six months, with a third of these orders to come from mobile devices.

Domino’s recently reported its half-year results and saw an improvement on almost every KPI. Same-store sales growth was strong, exceeding expectations in both Australia and Europe; margins improved and stall rollouts continued; the balance sheet strengthened, as did free cash flow; and, despite even lower debt, returns on equity increased. Domino’s concluded by upgrading its full-year 2012 guidance.

My friends at American Express should be able to confirm that while fashion retailing is one of the hardest gigs to be in, restaurants and cafes are one of the best. This is something Domino’s Pizza CEO Don Meij would know only too well. Despite challenging economic conditions, particularly in Victoria and New South Wales, same-store sales grew by almost 9% and total sales were up 11.2%. In Europe, where conditions are arguably much worse and youth unemployment is in the high double-digits, Domino’s recorded 12.6% total sales growth and 7.5% same-store sales growth. By the end of financial year 2012, another 60 to 70 stores will have been opened, net profit is expected to grow by 20% (despite adverse currency movements), and same-store sales growth is expected to be in the order of 5 to 7%.

In the last three years, earnings per share have doubled (no doubt the company has also taken market share from its peers, such as KFC) and despite a substantial decline in borrowings, return on equity has increased from 17% to 23% (see Skaffold.com screenshot below)Rising returns on equity, with little or no debt, is an indication of powerful business economics. Generally, as a company gets larger, its returns on equity stabilise or decline. Domino’s, however, enjoys an ability to raise prices and, some say, reduce pizza sizes without a detrimental impact on volume sales. This is, in my estimation, the most valuable competitive advantage it has. Granted, it’s a surprising conclusion to put forward for a franchisee (for a look at how things can go wrong for a franchisee company, look no further than Collins Foods).

Dominos displays declining debt (red columns), rising equity (grey columns), rising return on equity (blue line) and rising profits (green line). Source: Skaffold.com

Since 2004, Domino’s profits have increased 40.11% p.a. from $1.954 million to $20.7 million. To generate this $18.759m increase in profit, shareholders have tipped in an additional $64.37 million of equity and left in earnings of $34.82 million. In other words every additional dollar contributed and retained has returned around 19%. During the period under review the company has also reduced its borrowings by $9.11 million from $24.65 million it held in 2004 to $15.54 million at the end of FY2011.

Analysts worry about the risks associated with growing a business in Europe in the present climate. Rising commodity input prices, including oil for delivery vehicles and wheat for flour, and the stronger Australian dollar are also points of concern. In the face of these perceived challenges, the company continues to grow and expand its margins. It also expects greater than 25% profit growth from Australia within three years. Clearly, Domino’s competitive advantages are proving those analysts who said Australia was ‘ex-growth’ wrong. And the company is also moving to electric delivery scooters to hedge against higher fuel prices.

Domino is a high quality business – Source: Skaffold.com

I have not been able to buy Domino’s shares – as much as I would like to – because they have not been cheap enough for me. My valuation is based on the idea that I want to reduce my risks as much as possible by ensuring I obtain a bargain. DMP has simply never traded at a bargain price. But with a price close to $9.00 today, you could (admittedly with the benefit of hindsight) put forward the argument that the $2.65 the shares traded at in 2009 was every bit a bargain. The issue is simply the discount rate that I am willing to use to arrive at my valuation. If I use 8% to 9%, my valuation approximates the lower historical prices. But is 8-9% enough? I think not.

What would you pay for a business earning $25 million this year and $29 million next year, perhaps $35 million the year after that? If you said $300 million or $350 million, I’d label you a value investor, but today the market capitalisation is more than half a billion dollars. At that kind of multiple, I would guess the growth has been ‘priced in’. I would rather be certain of a modest return than hopeful of a great one, and at current prices – despite the obvious track record of the company and the very great skill of its management – I think buyers are being hopeful. Unless, of course, they know a takeover is imminent.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author, Skaffold Chairman and Fund Manager, 27 March 2012.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Investing Education, Value.able.