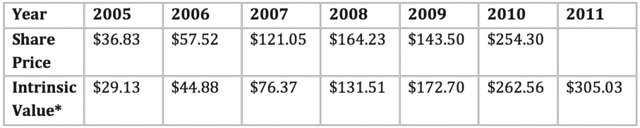

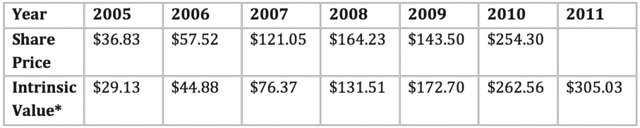

Did you know that the market capitalisation of Apple Inc. is now more than the entire equity markets of Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Greece combined? Its stunning. Surely Forrest Gump from Greenbow Alabama would be writing to Jenny with much enthusiasm. But what about its intrinsic value? Back in 2010 (http://rogermontgomery.com/is-apple-an-a1/) I wrote that Apple’s intrinsic value was higher than the share price at the time. The table below first published in July 2010 reveals the company’s pattern of rising intrinsic values. back then the price was indeed showing a small margin of safety.

A couple of blog readers have subsequently told me they purchased Apple shares and obviously they have done nicely. But what about today?

Only last year, when the share price hit $600 I wrote that I thought price had run ahead of intrinsic value (but not forecast intrinsic value) and the share price subsequently fell slightly. We also noted declining margins and market shares losses. But improving quarterly results and rising forecasts means revisions have resulted in IV estimates continuing their stellar rise so a revisit of our assumptions might be worth our time.

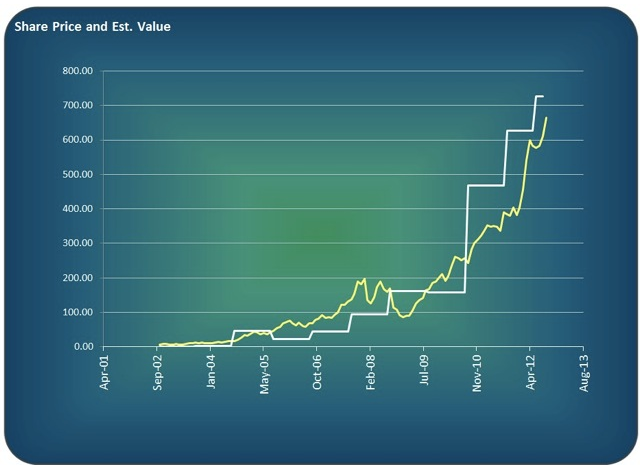

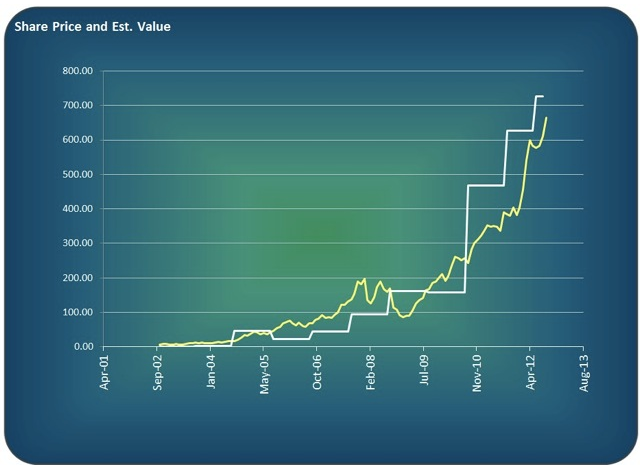

The graph below reveals that our ‘revised’ back-of-the-envelope intrinsic value estimate for Apple is forging ahead. If you are confident that Apple’s pipeline of products will usurp the competition, take back market share and fill Apple’s coffers towards 1000 billion dollars and that the iPhone 5 – expected to be revealed this week – will knock everyone’s socks off, then the massive rises in intrinsic value, might not seem so extreme.

Of course all intrinsic values are just estimates and while our haven’t done too badly for us – we’ve been spot on with BHP at $30 and done well on others – the reality is they can change dramatically as new information comes to hand.

So lets keep an eye on whether Apple impresses this week with its new release.