Energy / Resources

-

Is cash made from Sandalwood?

Roger Montgomery

October 28, 2010

A number of Value.able Graduates have asked me to share my view on TFS Corporation Ltd (ASX:TFC), the owner and manager of Indian sandalwood plantations in the east Kimberley region of Western Australia (an area I have visited and can’t wait to get back to).

A number of Value.able Graduates have asked me to share my view on TFS Corporation Ltd (ASX:TFC), the owner and manager of Indian sandalwood plantations in the east Kimberley region of Western Australia (an area I have visited and can’t wait to get back to).The first comment is from SI:

“I just had a look at TFS… wow is all I can say. I agree this is a monopoly in the making. They have control over customers with many signing up to a % of production years in advance and $$ to be set at point of sale. There appears to be medical interest developing, significant cosmetic and industry demand and cultural/religious needs not wants. So demand is very strong and lacking substitutes. On the supply side I see world supply is dwindling and TFS is really the only viable source – also natural/sustainable and green! There also appears to be huge barriers to entry for any competition and TFS is 15 years ahead of any rivals! So using Porters 5 forces: they have power over customers, power of suppliers, no realistic substitute, huge barriers to entry and a monopoly position… WOW they are also vertically integrated soil to end product! Also trading on a PE of approx 5, making money now growing trees, paying a dividend and yet to benefit from revenue from harvest….which appears to offer huge revenue flows starting in 2 years.”

And from James:

“… Their ROE is good, payout low and currently well under value.”

Putting aside the more than slight promotional tone of SI’s comments – thanks SI, it appears on first blush that TFS has several things going for it: bright prospects, possible competitive advantages, high levels of profitability and a valuation greater than the current price. Thanks SI for openly sharing your thoughts on the business.

To add my two cents worth, it would be useful to revisit a very important chapter of Value.able: Cashflow and Goodwill. I fear its importance may have been overlooked by readers. There are been precious few questions about, or discussion, of cashflow at my blog, even though it occupies a very large part of my time analysing companies. For TFS, in the current stage of its lifecycle, this chapter has many considerations for investors to take on board before jumping onto the Sandalwood bandwagon.

Let me start on page 147, third paragraph, bold font: “The cashflow of a company that you invest in must be positive rather than negative”. The reason I have emphasised this statement is because I want to make something very clear – reported accounting profits often bears little resemblance to the cash profits or cashflow of a company.

In business you can only spend cash. Indeed, cash is ‘king’. Try going to the local grocer, showing him an empty wallet and offering instead some accounting surplus to pay for the weeks fruit and veg. You will get just as far in business without real cash – unless the business has access to external funding to plug the gap. Please make sure you re-visit Chapter 9 of Value.able.

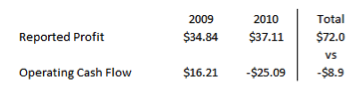

With re-reading from page 145 in mind, focus your attention to the profits and operating cash flows reported by TFS in 2009 and 2010.

TFS has not generated a single dollar of cumulative positive cash flow in the past two years. Despite reporting $72m in profits, TFS actually experienced a cash outflow of -$8.9m. In 2010, a record $37.11m in profits is matched by negative operating cash flows of -$25.09m. Remember page 147, third paragraph, bold font?

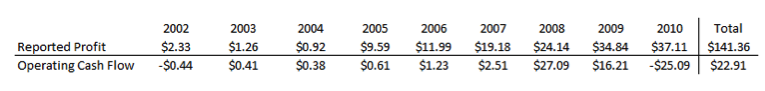

It could however be that the cash flow disparity is merely a timing issue. No problem; a longitudinal study will help. Turning our attention to the past 10 years, is the situation any better?

Total reported profits over this period equate to $141.36m, but this is money TFS cannot spend. The total of operating cash flows produced over the same period, money the business can spend, is significantly lower at $22.91m.

What if I now told you that over the same 10 years, the business had spent $77.43m on investments including property, plant and equipment, and paid $29.94m in dividends!

And all this from Cash Flow of only $22.91m? This is generally only achievable if a business has very accommodating shareholders and financiers – who, to date, have tipped in $61.14m in equity and $43.19m in debt to plug the hole.

Does this business meet Chapter 9’s description of a Value.able business?

Extraordinary businesses don’t have to wait for cash flow. Their already-entrenched competitive position ensures that cash flows readily into management’s hands to be re-deployed/re-invested (with shareholders best interests at heart), or returned.

TFS and many other businesses listed on the ASX are able to utilise various accounting standards to depict the appearance of a profitable business when they are in actual fact heavily reliant on external financing to fund and grow operations.

I am not saying in any way, shape or form that TFS is a business that will head down the same path as many in the sector before it – remember Great Southern Plantations and Timbercorp? TFS may soon produce fruit (so to speak). And if SI and management are right, the business offers “huge revenue flows starting in 2 years”, is a “monopoly in the making” and 2011 will see a significant increase in positive operating cash flow as settlement of institutional sales occurs throughout the year. If this occurs, the business may achieve an investment grade Montgomery Quality Rating (MQR).

I prefer to see runs on the scoreboard – a demonstrated track record – and profits being backed up by uninhibited cash streaming through the door before I open my wallet. Yes, one will miss opportunities adopting this approach but those fish you do catch are generally very good eating.

So until such time as TFS’s cash starts to flow, there are other cash-producing listed A1 businesses to choose from.

This brings up an important point to consider; make sure reported profits are backed up by cash flowing into the business. If it isn’t, be very conservative in your assumptions. Better still, move on to valuing businesses that are extraordinary, those with an MQR of A1, A2 and B1. TFS is a B3.

I will watch this one from the sidelines for now, even if I miss out on returns in the meantime.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 28 October 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources.

- 78 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Energy / Resources

-

Should I or shouldn’t I?

Roger Montgomery

October 12, 2010

QR National is the second biggest float in Australia’s history and if I, as a value investor, am to be focused on extraordinary businesses, bought at discounts to intrinsic value, then the second biggest float ever deserves some of my attention.

QR National is the second biggest float in Australia’s history and if I, as a value investor, am to be focused on extraordinary businesses, bought at discounts to intrinsic value, then the second biggest float ever deserves some of my attention.But is QR National an extraordinary business? And is it available at a discount to its intrinsic value? They are the questions I need to answer.

QR Limited reported a loss of $37 million in 2010 (The Prospectus Appendix reports the continuing operations of QR Limited lost $37 million in 2010). A company-wide restructure, combined with customers rolling off old contracts and onto new, more commercial ones, as well as continued growth in coal haulage volumes however, is expected to result in a profit of $369 million in 2012 (and possibly much higher beyond that).

QR National will start its listed life with a balance sheet that has about $6.8 billion of equity. If QR National hits its targeted profits and pays its estimated dividends over the next 18 months, that equity will grow to $7.3 billion (I have excluded the impact on equity of the proposed dividend reinvestment plan). And if QR National hits its 2012 profit forecast, return on average equity will reach 5.1 per cent.

(POSTSCRIPT; Much is being made of the profits beyond 2012 and the return on the $3 billion invested. I had the opportunity to discuss this with L.Hockridge and he pointed to the prospectus forecast for an EBITDA run rate of $170-$190 million. Aside from the fat that EBITDA is nonsense the NPAT return on capital at maximum capacity will be about 6%. I talk about this below so I am not too worried about using the 2012 for a few years beyond it. In any event if 2015 and beyond is where the rewards are; why the rush to invest today?)

Given that I can invest in companies generating 40%, 50%, 60% even 80% returns on equity, should I consider a return that is less than that which cash in the bank generates?

Because the dividend yield is so miserly (and because of negative cash flow after capital expenditure, those dividends are effectively funded out of borrowings) the company is being pitched as a growth stock and growth story. Growth in coal volumes transported is the validation for the claim. But when a company generates a 5% return on the profits they keep, you don’t want it to grow. It is better they hand all the profits back to you so that you can put the money in the bank and get a higher and safer return. Of course they can’t hand the profits back to you because the cash flow won’t support it for reasons I explain next.

QR National is a capital intensive business and even before dividends are paid, the cash flow will be negative. Between 2008 and 2012 (5 years) QR National will have expended $7.2 billion on ‘capex’ and the company will need to borrow $1.5 billion in the next few years (the prespectus explains it will draw on over $2 billion). This will partially cover the gap between the capex and the cash form operations of $3.4 billion. The returns the company will be aiming for on this debt funding could be nine per cent or more, but my estimate is that the $170-$190 million in EBITDA from its GAPE project disclosed in the prospectus will be whittled down considerably by depreciation, interest and tax, such that the additional contribution to return on equity of the whole group may not be so significant.

As an aside the prospectus spends a great deal of time focusing on EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) but as Charlie Munger once observed, whats the point of looking at “earnings before costs”? And as Buffett noted, the “tooth fairy” doesn’t pay for these things. Depreciation is a very real expense even though many finance professionals treat it as a non cash accounting item. In reality when depreciation is based on the historical cost of an item, it will under-provide for the true cost of maintaining and ultimately replacing that item. This is because the depreciation is based on the purchase price of the item many years ago, but maintaining and replacing it will suffer the impact of inflation. Thinking about it another way; imagine employing a thousand people for ten years but paying for them upfront and expensing the cost over ten years – would you then say the item is non cash and can be ignored? The real cost of employing these people will be higher than the depreciation suggests – they will demand salary increases. Looking at earnings before real costs is nonsense. Buffett’s advice from his 1989 letter to Berkshire Shareholders is even less accommodating: “Whenever an investment banker starts talking about EBDIT – or whenever someone creates a capital structure that does not allow all interest, both payable and accrued, to be comfortably met out of current cash flow net of ample capital expenditures – zip up your wallet.”

One other point: it appears to me that forecast profits (and by inference the 2012 Return on equity of circa 5%), may be boosted by some permitted accounting tricks. The future profits may be boosted by the capitalisation of interest on debt used to finance assets under construction. In other words not all of the interest expense in 2012 is flowing through the forecast profit and loss statement. Some of it will be capitalised (converted to an asset on the balance sheet). Telstra has done this with software development expenses and the end result is a profit figure that looks better than economic reality. For QR National it means that $369 million profit reflects accounting reality rather than economic reality.

I appreciate two things about this float. First, some of the smartest operators and management in the country are now driving it and as they point out, quite rightly, prospectus requirements limit their ability to discuss what happens beyond 2012 (but beyond 2012 anything can change, even management themselves). If however, it is the case that returns on equity will creep towards double digits after 2012, then I must ask myself if there is there any urgency to buy today?

The risk of course is the cost associated with paying a higher price for the shares at some future date when the wonderful performance is confirmed. The second thing I appreciate is that I cannot predict what the share price will do. The vendors and their advisors are pulling out every device designed to support the price of the shares after the float. There is the loyalty bonus that incentivises retail investors not to sell until December next year, and there’s the greenshoe permit that allows the managers of the float to step in and buy shares in the aftermarket. The share price may very well perform brilliantly. I am the first to admit that I am no good at predicting what the shares will do. That is the main reason why I always say you must seek and take personal professional advice. Your adviser is the only person who understands whether QR National or any company and their shares are suitable for you.

I estimate QR National’s shares have a 2012 intrinsic value of between $1.09 and $1.48, but thats in 18 months time. Given there will be 2.44 billion shares on issue, the intrinsic value of the whole business is about $3.7 billion in 2012. The intrinsic value is necessarily less than the equity or book value on the balance sheet because the equity is forecast to produce a lower return than that which I require from a business. The vendors want you today to pay up to double the 2012 intrinsic value ($2.40-$2.80 per share – loyalty bonus and Queensland resident bonus excluded).

I may indeed miss out on some gains if I don’t participate in the float, and I may miss out on very substantial gains. Of course there is the risk of loss too if I do participate. While I might be ok with either scenario, you may not be and so YOU MUST SEEK AND TAKE PERSONAL PROFESSIONAL ADVICE. My comments are general in nature and I have not taken into account anything about you or your financial needs and circumstances. If you want advice about what to do regarding the QR National float, speak to your advisor and if you haven’t got one, seek one out BEFORE doing or not doing anything.

Postscript: as one of my friends, Chris – also a fund manager – noted this morning: “I haven’t looked at the detail yet, but thought it was worth pointing out that the EV/EBITDA multiples they’re using might be a touch disingenuous. QR are using FY12 earnings on today’s balance sheet (i.e. current net debt of $500 million) despite the fact that they’ll have to drw down on at least $1.5 billion of further debt to generate those earnings. Essentially you might like to have someone check if they might be using today’s balance sheet and tomorrow’s earnings to lower the multiple.”

On a more navel gazing note…

Short-term price direction is not the trigger for a change of heart towards a company. Indeed, a falling price for an A1 business generally represents an opportunity. Sometimes however the nature of price changes has me sitting up and taking notice – being alert rather than alarmed.

Currently, JB Hi-Fi’s share price has been heading in the opposite direction to that of most of the A1 companies that I am following. Such determined selling has often been the precursor to an announcement. Let me make it clear that other than knowing JBH will hold its AGM tomorrow in Melbourne, I don’t know whether an announcement, for example a trading update, will be forthcoming or not. The rather unidirectional nature of the price changes however, often bodes poorly for the contents of any announcement. Keep a watchful eye therefore on JB Hi-Fi.

I found at my recent visits to a handful of JBH stores that they were busier than ever. But the recent share price changes suggests someone is nervous.

The only subsequent thought I have had is that the high Australian dollar has resulted in price deflation, which JB Hi-Fi’s competitors will take advantage of and the company will have to respond to by lowering prices, putting pressure on gross margins. JB Hi-Fi remains at a discount to my current estimates of intrinsic value and as I just mentioned, I generally take advantage of the market and its Wallet rather than listen to its Wisdom.

Keep an eye on JBH and any news from tomorrow’s AGM in Melbourne particularly about margins, deflation and the Aussie dollar at 11.30am.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 12 October 2010.

Postscript #2: JBH AGM notes. first quarter trading has improved. Total store sales are up 12.2% but behind BUDGET (not last year comprables) by 5%. JBH expects to make it up over CHristmas but evidently they didn’t mention the previous guidance of 17% growth in sales (perhaps this IS budget). Store roll out is on track and 18 additional stores are expected to be opened in the current financial year. They DID say that they are well placed to maintain margins despite discounting. Newspapers this morning point to a raft of new games to be released (JBH is the second biggest retailer of computer games) for Christmas.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources.

- 170 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Energy / Resources

-

How does cash flow through Decmil?

Roger Montgomery

September 14, 2010

I met with Justine and Dickie, the CFO and COO of Decmil recently, and got a good understanding of how cash flows through the business.

I am comfortable that the disastrous acquisition track record of the past is now just that; past. The board now appears stable, culture within the business appears to be excellent and if Justine and Dickie’s enthusiasm is anything to go by, their reputation, which has taken 31 years to build, will see them continue to secure projects from blue chip clients (don’t ask me what ‘blue chip’ means).

There are of course macro risks in supplying picks and shovels. The GFC for example didn’t dent BHP and RIO’s aspirations, but it did dent the banks’ willingness to lend on new projects. A macro shock could thwart the capex plans of many resource companies and this would inevitably impact Decmil and its peers. Operating leverage however is not as high as you may think and I invite you to investigate.

So go forth and conduct your own research and as always, seek professional financial advice. You can also use the steps in Value.able to calculate the value of Decmil yourself.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 14 September 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources.

- 75 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Energy / Resources

-

Has BHP and WOW survived the reporting season snow storm?

Roger Montgomery

August 31, 2010

The final reporting season avalanche has coincided with a serious amount of snow in the high plains. No matter where one turns, there’s no escaping heavy falls. More than 300 companies have reported in five days and I am completely snowed under. If you haven’t yet received my reply to your email, now you understand why.

The final reporting season avalanche has coincided with a serious amount of snow in the high plains. No matter where one turns, there’s no escaping heavy falls. More than 300 companies have reported in five days and I am completely snowed under. If you haven’t yet received my reply to your email, now you understand why.To put my week into perspective, up until last Monday morning, around 200 companies had reported (see my Part I and Part II reporting season posts). This week’s 300-company avalanche brought the total to 500. I’m sorry to report that without a snowplough, I have fallen behind somewhat. Around 200 are left in my in-tray to dig through. I will get to them!

Thankfully, there are only a few days left in the window provided by ASX listing Rule 4.3B in which companies with a June 30 balance date must report, and by this afternoon, I will be able to appreciate the backlog I have to work through. So not long to go now…

Nonetheless, today I would like to talk about two companies which I am sure many of you are interested in: BHP and Woolworths. Both received the ‘Montgomery’ B1 quality score this year.

For the full year, BHP reported a net profit of around A$14b and a 27% ROE – a big jump on last years $7b result, which was impacted by material write-offs. Backing out the write-offs, last years A$16b profit and ROE of 36% was a better result than this years. The fall in the business’s profitability has likewise seen my 2010 valuation fall from $34-$38 to around $26-$30 per share, or a total value of $145b to $167b (5.57 billion shares on issue).

With the shares trading in a range of $35.58 to $44.93 ($198b to $250b) for the entire 52 weeks, it appears that the market and analysts expected much better things. While they didn’t come this year, are they just around the corner? I will let you be the judge.

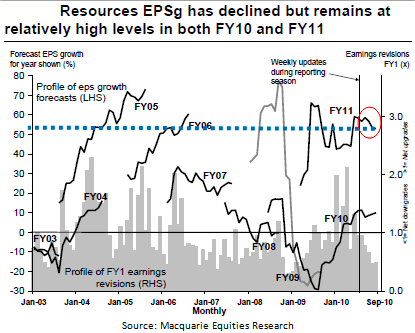

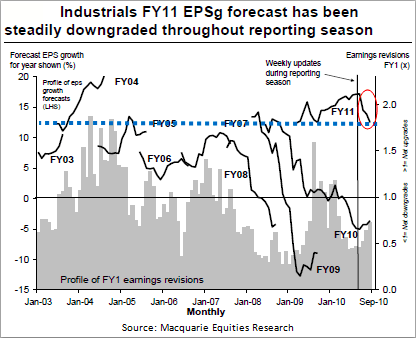

The “market” (don’t ask who THAT is!) estimates resource company per share earnings growth of 50 per cent for 2011. I have drawn a thick blue line to show this on the left hand side of the following graph so you can see where my line intersects.

BHP has a large weighting in the resources sector, so the forecast increase in net earnings by 57 per cent to A$22b is having a material impact on the sector average. Importantly, the forecast growth rate is similar to those seen in 2005 and 2006 when the global economy was partying like there was no GFC. Call me conservative, but I reckon those estimates are a little optimistic in todays environment.

As you know I leave the forecasting of the economy and arguably puerile understandings of cause-and-effect relationships to those whose ability is far exceeded by their hubris. Its worth instead thinking about what BHP has itself stated; “BHP Billiton remains cautious on the short-term outlook for the global economy”.

Given my conservative nature when it comes to resource companies and the numerous unknowns you have to factor in, I would be inclined to be more conservative with my assumptions when undertaking valuations for resource companies. If you take on blind faith a A$22b profit, BHP’s shares are worth AUD $45-$50 each.

But before you take this number as a given, note the red circle in the above chart. Earnings per share growth rates are already in the process of being revised down. I would expect further revisions to come. And if my ‘friends-in-high-places’ are right, it’s not out of the realm of possibilities to see iron ore prices fall 50 per cent in short order. You be the judge as to how conservative you make your assumptions.

A far simpler business to analyse is Woolworths and for a detailed analysis see my ValueLine column in tonight’s Eureka Report. WOW reported another great result with a return on shareholders’ funds of 28% (NPAT of just over $2.0b) only slightly down from 29% ($1.8b) last year. This was achieved on an additional $760m in shareholders’ funds or a return on incremental capital of 26% – and that’s just the first years use of those funds. This is an amazing business given its size.

My intrinsic value rose six per cent from $23.71 in 2009 to $25.07 in 2010. Add the dividend per share of $1.15 and shareholders experienced a respectable total return.

Without the benefit of the $700 million buyback earnings are forecast by the company to rise 8-11 per cent. However, the buyback will increase earnings per share and return on equity, but decrease equity. The net effect is a solid rise in intrinsic value. Instead of circa $26 for 2011, the intrinsic value rises to more than $28.

But it’s not the price of the buyback that I will focus on as that will have no effect on the return on equity and a smaller-than-you-think effect on intrinsic value (thanks to the fact that only around 26 million shares will be repurchased and cancelled). What I am interested in is how the buyback will be funded. You see WOW now need to find an additional $700m to undertake this capital management initiative. So where will the proceeds come from? That sort of money isn’t just lying around. The cash flow statement is our friend here.

In 2010 Operating Cash Flow was $2,759.9 of which $1,817.7m was spent on/invested in capital expenditure, resulting in around $900m or 45% of reported profits being free cash flow – a similar level to last year. A pretty impressive number in size, but a number that also highlights how capital intensive owning and running a supermarket chain can be.

From this $900m in surplus cash, management are free to go out and reinvest into other activities including acquisitions, paying dividends, buybacks and the like. So if dividends are maintained at $1.1-$1.2b (net after taking into account the DRP), that means the business does not have enough internally generated funds to undertake the buyback. They are already about $200-$300m short with their current activities. In 2010 WOW had to borrow $500m to make acquisitions, pay dividends and fund the current buyback.

Source: WOW 2010 Annual Report

Clearly the buyback cannot be funded internally, so external sources of capital will be required. In the case of the recently announced buyback it appears the entire $700m buyback will need to be financed via long-term debt issued into both domestic and international debt capital markets, which management have stated will occur in the coming months. They also have a bank balance of $713m, but this has not been earmarked for this purpose.

Currently WOW has a net debt-equity ratio of 37.4 per cent so assuming the buyback is fully funded with external debt, the 2011 full year might see total net gearing rise to $4.250b on equity of $8,170b = 52 per cent.

A debt-funded buyback will be even more positive for intrinsic value than I have already stated, but of course the risk is increased.

While 52 per cent is not an exuberant level of financial leverage given the quality of the business’s cash flows, I do wonder why Mr Luscombe and Co don’t suspend the dividend to fund the buyback rather than leverage up the company with more debt? This is particularly true if they believe the market is underpricing their shares.

Yes, it’s a radical departure from standard form.

I will leave you with that question and I will be back later in the week with a new list of A1 and A2 businesses. Look out for Part Three.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 31 August 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Consumer discretionary, Energy / Resources.

-

Can Ausenco be an A1 again?

Roger Montgomery

June 18, 2010

I was on the Sky Business Channel’s Your Money Your Call a couple of weeks ago. The next day Phil let me know how disappointed he was on my Facebook page – his email wasn’t featured on the show and he couldn’t get through on the phone. I should let you know that until I am hosting a program (don’t get any ideas!), I don’t have a say in which calls are taken and what emails are featured. I did however promise to share my observations on Ausenco with the disclaimer that they are didactic.

Up until 2008 Ausenco (AAX) was a darling of the market – indeed it had reason to be. It had a track record of being an A1 business and in 2007 was generating a profit $41.5m on only $56m of equity – a stellar 95% return. A 2007 estimate of AAX’s intrinsic value would be something like $15.07.

But with the share price now trading around $2.33 and my current valuation at $1.54, something has changed. Why has Ausenco fallen on such tough times?

In 2007-8 Ausenco went on somewhat of a buying binge. To diversify away from the operations of mining and minerals processing, PSI, Vector and Sandwell were added to Ausenco’s business. Looking at the share price today, compared to two years ago it appears Ausenco paid a very high price for this strategy.

At the end of 2007 a significant portion of Ausenco’s $56m of equity was cash. The business had only $7m of debt. Up until that time shareholders had grown the business by simply investing $11.5m of their own equity and retaining a cumulative $45.7m in profits. A nice position and in my opinion, very attractive. Ausenco was a small, highly profitable, organically-grown and well-run business.

By the end of 2008 growth was turbocharged. The combination of substantial acquisitions however saw an additional $106.6m of equity raised and debt jumped to $66. In other words, shareholders equity ballooned by 325%, to $182m, compared to the previous year.

With this aggressive growth came a host of challenges. Running a focused small business is a much easier task than steering a larger ship that has diversified into a ‘pit to port’ engineering business.

And by 2009 the numbers agreed. A profit of $20.3m was reported, but $260m was needed to produce it. So the profit was lower than 2007, but significantly more money had been contributed.

Ausenco was far more valuable as a small business than it is as a larger one, as anyone holding the shares through this period can attest.

As an investor, you should ask questions when a small, highly focused and highly profitable business becomes enamoured with the idea that bigger is better. Some may argue that the GFC is partly to blame. My response is to take a look at another business in the same sector, Monadelphous – one of my A1s and a business that has never attempted to grow beyond what Buffett refers to as its circle of competence.

Unlike Monadelphous, Ausenco has slipped from an A1 to an A4. Yes its still high quality (A), but with a performance rating of 4 (5 being the lowest), its predictability is not something to be excited about.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 18 June 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources.

- 10 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Energy / Resources

-

Can a bubble be made from Coal?

Roger Montgomery

April 19, 2010

Serendibite is arguably the rarest gem on earth. Three known samples exist, amounting to just a few carats. When traded at more than $14,000 per carat, the price is equivalent to more than $2 million per ounce. But that’s serendibite, not coal.

Serendibite is arguably the rarest gem on earth. Three known samples exist, amounting to just a few carats. When traded at more than $14,000 per carat, the price is equivalent to more than $2 million per ounce. But that’s serendibite, not coal.Coal is neither a gem nor rare. It is in fact one of the most abundant fuels on earth and according to the World Coal Institute, at present rates of production supply is secure for more than 130 years.

The way coal companies are trading at present however, you have to conclude that either coal is rare and prices need to be much higher, or there’s a bubble-like mania in the coal sector and prices for coal companies must eventually collapse.

The price suitors are willing to pay for Macarthur Coal and Gloucester Coal cannot be economically justified. Near term projections for revenue, profits or returns on equity cannot explain the prices currently being paid.

To be fair, a bubble guaranteed to burst is debt fuelled asset inflation; buyers debt fund most or all of the purchase price of an asset whose cash flows are unable to support the interest and debt obligations. Equity speculation alone is different to a bubble that an investor can short sell with high confidence of making money.

The bubbles to short are those where monthly repayments have to be made. While this is NOT the case in the acquisitions and sales being made in the coal space right now, it IS the case in the macroeconomic environment that is the justification for the purchases in the coal space.

China.

If you are not already aware, China runs its economy a little differently to us. They set themselves a GDP target – say 8% or 9%, and then they determine to reach it and as proved last week, exceed it. They do it with a range of incentives and central or command planning of infrastructure spending.

Fixed asset investment (infrastructure) amounts to more than 55% of GDP in China and is projected to hit 60%. Compare this to the spending in developed economies, which typically amounts to circa 15%. The money is going into roads, shopping malls and even entire towns. Check out the city of Ordos in Mongolia – an entire town or suburb has been constructed, fully complete down to the last detail. But it’s empty. Not a single person lives there. And this is not an isolated example. Skyscrapers and shopping malls lie idle and roads have been built for journeys that nobody takes.

The ‘world’s economic growth engine’ has been putting our resources into projects for which a rational economic argument cannot be made.

Historically, one is able to observe two phases of growth in a country’s development. The first phase is the early growth and command economies such as China have been very good at this – arguably better than western economies, simply because they are able to marshal resources perhaps using techniques that democracies are loath to employ. China’s employment of capital, its education and migration policies reflect this early phase growth. This early phase of growth is characterised by expansion of inputs. The next stage however only occurs when people start to work smarter and innovate, becoming more productive. Think Germany or Japan. This is growth fuelled by outputs and China has not yet reached this stage.

China’s economic growth is thus based on the expansion of inputs rather than the growth of outputs, and as Paul Krugman wrote in his 1994 essay ‘The Myth of Asia’s Miracle’, such growth is subject to diminishing returns.

So how sustainable is it? The short answer; it is not.

Overlay the input-driven economic growth of China with a debt-fuelled property mania, and you have sown the seeds of a correction in the resource stocks of the West that the earnings per share projections of resource analysts simply cannot factor in.

In the last year and a half, property speculation has reached epic proportions in China and much like Australia in the early part of this decade, the most popular shows on TV are related to property investing and speculation. I was told that a program about the hardships the property bubble has provoked was the single most popular, but has been pulled.

Middle and upper middle class people are buying two, three and four apartments at a time. And unlike Australia, these investments are not tenanted. The culture in China is to keep them new. I saw this first hand when I traveled to China a while back. Row upon row of apartment block. Empty. Zero return and purchased on nothing other than the hope that prices will continue to climb.

It was John Kenneth Galbraith who, in his book The Great Crash, wrote that it is when all aspects of asset ownership such as income, future value and enjoyment of its use are thrown out the window and replaced with the base expectation that prices will rise next week and next month, as they did last week and last month, that the final stage of a bubble is reached.

On top of that, there is, as I have written previously, 30 billion square feet of commercial real estate under debt-funded construction, on top of what already exists. To put that into perspective, that’s 23 square feet of office space for every man, woman and child in China. Commercial vacancy rates are already at 20% and there’s another 30 billion square feet to be supplied! Additionally, 2009 has already seen rents fall 26% in Shanghai and 22% in Beijing.

Everywhere you turn, China’s miracle is based on investing in assets that cannot be justified on economic grounds. As James Chanos referred to the situation; ‘zombie towns and zombie buildings’. Backing it all – the six largest banks increased their loan book by 50% in 2009. ‘Zombie banks’.

Conventional wisdom amongst my peers in funds management and the analyst fraternity is that China’s foreign currency reserves are an indication of how rich it is and will smooth over any short term hiccups. This confidence is also fuelled by economic hubris eminating from China as the western world stumbles. But pride does indeed always come before a fall. Conventional wisdom also says that China’s problems and bubbles are limited to real estate, not the wider economy. It seems the flat earth society is alive and well! As I observed in Malaysia in 1996, Japan almost a decade before that, Dubai and Florida more recently, never have the problems been contained to one sector. Drop a pebble in a pond and its ripples eventually impact the entire pond.

The problem is that China’s banking system is subject to growing bad and doubtful debts as returns diminish from investments made at increasing prices in assets that produce no income. These bad debts may overwhelm the foreign currency reserves China now has.

Swimming against the tide is not popular. Like driving a car the wrong way down a one-way street, criticism and even abuse follows the investor who seeks to be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy. Right now, with analysts’ projections for the price of coal and iron ore to continue rising at high double digit rates, and demand for steel, glass, cement and fibre cement looking like a hockey stick, its unpopular and decidedly contrarian to be thinking that either of these are based on foundations of sand or absent any possibility of change.

The mergers and acquisitions occurring in the coal space now are a function of expectations that the good times will continue unhindered. I hope they’re right. But witness the rash of IPOs and capital raisings in this space. Its not normal. The smart money might just be taking advantage of the enthusiasm and maximising the proceeds from selling.

A serious correction in the demand for our commodities or the prices of stocks is something we don’t need right now. But such are the consequences of overpaying.

Overpaying for assets is not a characteristic unique to ‘mum and dad’ investors either. CEO’s in Australia have a long and proud history of burning shareholders’ funds to fuel their bigger-is-better ambitions. Paperlinx, Telstra, Fairfax, Fosters – the past list of companies and their CEO’s that have overpaid for assets, driven down their returns on equity and made the value of intangible goodwill carried on the balance sheet look absurd is long and not populated solely by small and inexperienced investors. When Oxiana and Zinifex merged, the market capitalisations of the two individually amounted to almost $10 billion. Today the merged entity has a market cap of less than $4 billion.

The mergers and takeovers in the coal space today will not be immune to enthusiastic overpayment. Macarthur Coal is trading way above my intrinsic value for it. Gloucester Coal is trading at more than double my valuation for it.

At best the companies cannot be purchased with a margin of safety. At worst shares cannot be purchased today at prices justified by economic returns.

Either way, returns must therefore diminish.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 19 April 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources, Insightful Insights.

-

Is Australia’s future written inside a fortune cookie?

Roger Montgomery

March 4, 2010

On 3 March I shared my thoughts about the future of Australian companies that supply directly or indirectly, the Chinese building industry, or have more than 70% of their revenues or profits reliant on China with subscribers of Alan Kohler’s Eureka Report. Following are my insights…

Glancing over yet another set of numbers as reporting season draws to a close, my mind started to wander as I wade through forecasts for one, two and three years hence. I began to consider what might happen that could take the shine off these elaborate constructions and which companies are in the firing line. Consider Rio Tinto, which, in an effort to make itself “takeover proof” back in 2007, loaded itself up with debt up to acquire the Canadian aluminium company Alcan. It paid top-of-the-market multiples just 12 months before the biggest credit crunch in living memory forced it to sell assets, raise capital and destroy huge amounts of shareholder value. Do you think they saw that coming?

Before I elaborate on events that could unfold, allow me to indulge in a bit of history and take you back to the mid-1990s when I was in Malaysia and the Kuala Lumpur skyline was filled with cranes because of a credit-fuelled speculative boom. It was the same throughout the region.

A year or so after my visit, the Asian tiger economies were in trouble and the Asian currency crisis was in full flight. These are the returns that are produced by unjustified, credit-fuelled “investing” unsupported by demand fundamentals.

In December 2007, as I travelled to Miami, I experienced a distinct feeling of déjà vu as I once again witnessed residential and commercial property construction fuelled by low interest rates and easy credit, unsupported by any real demand.

These are not isolated incidences. Japan, Dubai, Malaysia, the US. Credit fuelled speculative property booms always end badly.

So what does this have to do with your Australian share portfolio? Australia’s economic good fortune lies in its proximity – and exports of coal and iron ore – to China. Much of those commodities go into the production of steel, one of the major inputs in the building industry.

In China today there is, presently under construction and in addition to the buildings that already exist, 30 billion square feet of residential and commercial space. That is the equivalent of 23 square feet for every single man, woman and child in China. This construction activity has been a key driver of Chinese capital spending and resource consumption.

About two years ago if you looked at all the buildings, the roads the office towers and apartments under construction the only thought to pop into your head would be to consider how much energy would be required to light and heat all those spaces.

But that won’t be necessary if they all remain empty. In the commercial sector, the vacancy rate stands at 20% and construction industry continues to build a bank of space that is more than required for a very, very long time.

Because of this I am more than a little concerned about any Australian company that sells the bulk of its output to the Chinese, to be used in construction. That means steel and iron ore, aluminium, glass, bricks, fibre cement … you name it.

Last year China imported 42% more iron ore than the year before, while the rest of the world fell in a heap. It consumes 40% of the world’s coal and the growth has increased Australia’s reliance on China; China buys almost three-quarters of Australia’s iron ore exports – 280 million of their 630 million tonne demand.

The key concern for investors is to examine the valuations of companies that sell the bulk of their output to China. Any company that is trading at a substantial premium to its valuation on the hope that it will be sustained by Chinese demand, without a speed hump, may be more risk than you care for your portfolio to endure.

The biggest risks are any companies that are selling more than 70% of their output to China but anything over 20% on the revenue line could have major consequences.

BHP generates about 20%, or $11 billion, of its $56 billion revenue from China; and Rio 24%, or $11 billion, from its $46 billion revenue. BHP’s adjusted net profit before tax was $19.8 billion last year and Rio’s was $8.7 billion.

While BHP’s profitability would be substantially impacted by any speed bumps that emerge from China, the effect on Rio Tinto would be far worse.

According to my method of valuation, Rio Tinto is worth no more than its current share price and while the debt associated with the $43 billion purchase of Alcan is declining, the dilutive capital raisings (so far avoided by BHP) have been disastrous for its shareholders.

As a result, return on equity is expected to fall from 45% to 16% for the next three years. Most importantly the massive growth in earnings for the next three years is driven by the ever-optimistic analysts who are relying on China’s growth to extend in a smooth upward trajectory.

Go through your portfolio: do you own any companies that supply directly or indirectly, the Chinese building industry, have more than 70% of their revenues or profits reliant on China and are trading at steep premiums to intrinsic value?

Make no mistake: Australia’s future is written inside a fortune cookie – some companies’ more than others.

Subscribe to Alan’s Eureka Report at www.eurekareport.com.au.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 4 March 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources, Insightful Insights.

-

Will 2010 be the year of inflation, interest rates, commodities and Oil Search?

rogermontgomeryinsights

January 30, 2010

Welcome back. On Christmas Eve, just before I left for my annual family holiday, I said that this year would be fascinating in terms of inflation, interest rates and commodities prices. Interest rates can be ticked off – the topic has already been front page news and I expect the subject to hot up even more over the coming year.

Inflation and commodities however are arguably even more interesting. When money velocity picks up in the US – that is, the speed with which money changes hands – inflation could be a problem. I don’t know whether that will be this year or not, but I do know that at some point the benign inflation and extraordinarily low interest rates will be nothing but a fond memory.

One of the places inflation presents is in commodity prices, and there is no shortage of very smart, successful and wealthy people – Jim Rogers is one – who believe the bull market in commodities is far from over. continue…

by rogermontgomeryinsights Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources, Insightful Insights.

-

Wishing you a safe and happy Christmas

rogermontgomeryinsights

December 24, 2009

I am away for Christmas and January and will only be publishing thoughts to the blog on a spasmodic basis.

If you go to my website, www.rogermontgomery.com, and register for my book or send a message to me, I will let you know via email when I am back on deck.

I expect 2010 will be a very interesting year on the inflation, interest rate and commodity fronts so stay tuned and focus on understanding what is driving a company’s return on equity and how to arrive at its value.

Before doing anything seek always professional advice, but zip up your wallet if you hear the words “only trade with what you can lose”. I don’t like losing money at any time and neither should you.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 23 December 2009

by rogermontgomeryinsights Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources, Insightful Insights, Market Valuation.

-

Can you value commodity type companies?

rogermontgomeryinsights

December 24, 2009

Commodity prices… can anyone predict their movements? Driven by supply and demand, and exaggerated by speculation, predicting the price of oil, iron ore, coal, diamonds and titanium is an almost impossible task. \It is however a task that is required if you are planning to buy shares in a mining company. Ruling out mining exploration companies that make no profit, and whose race to a valuation of zero is only retarded by the amount of cash remaining in the bank and measured by a ratio called the cash ‘burn’ rate, we are left with the producers.

For reasons mentioned above, no mining company is easy to value, however some lend themselves to valuations better than others. The best are those that are large, broadly diversified and relatively stable. BHP immediately comes to mind. Born as a silver and lead mine in Broken Hill in 1885, BHP, following the 2001 merger between it and Billiton, is now the world’s largest mining company with operations from Algeria to Tobago and everywhere in between.

But even BHP cannot escape the commodity cycle and this can be seen in the swings in its valuations in the past. BHP’s valuation can be $48 in one year (2008) and $13 the next (2009). This “valuation volatility” is vastly different to JB Hi-Fi, for example, whose value has risen from less than a dollar in 2003 to $20 to $24 today and in a steady ‘staircase’ fashion.

Many of you have asked me for a valuation for BHP. Using the earnings estimates of the rated analysts on the company, there is clearly some optimism about BHP’s prospects. Returns on equity are expected to rise from 17.5% this year to 24% next year, and circa 28% in 2011 and 2012. These numbers however are still lower than the rates of return the company generated between 2005 and 2007. The estimate I come up with for BHP using the actual estimates of the rated analysts is a value of A$36.56, and if the analysts are right, the value rises dramatically in future years.

Warren Buffett doesn’t like businesses that are price takers – commodity type businesses. The reason is that it is impossible to forecast future rates of return on equity with any confidence. BHP reflects this historically. BHP is big enough now that in some cases it is calling the (price) shots, but don’t forget we are talking about capital-intensive businesses.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 23 December 2009

by rogermontgomeryinsights Posted in Companies, Energy / Resources.

- save this article

- POSTED IN Companies, Energy / Resources