The conga line of loss making IPOs is a worry..

There are plenty of charts doing the rounds showing the rising percentage of companies listing in the US, that are losing money. Uber is perhaps the best recent example, which we wrote about and suggested it might be a great short selling opportunity.

And while many fundies are suggesting that current conditions are eerily similar to the tech boom of 1999 and 2000, there are differences.

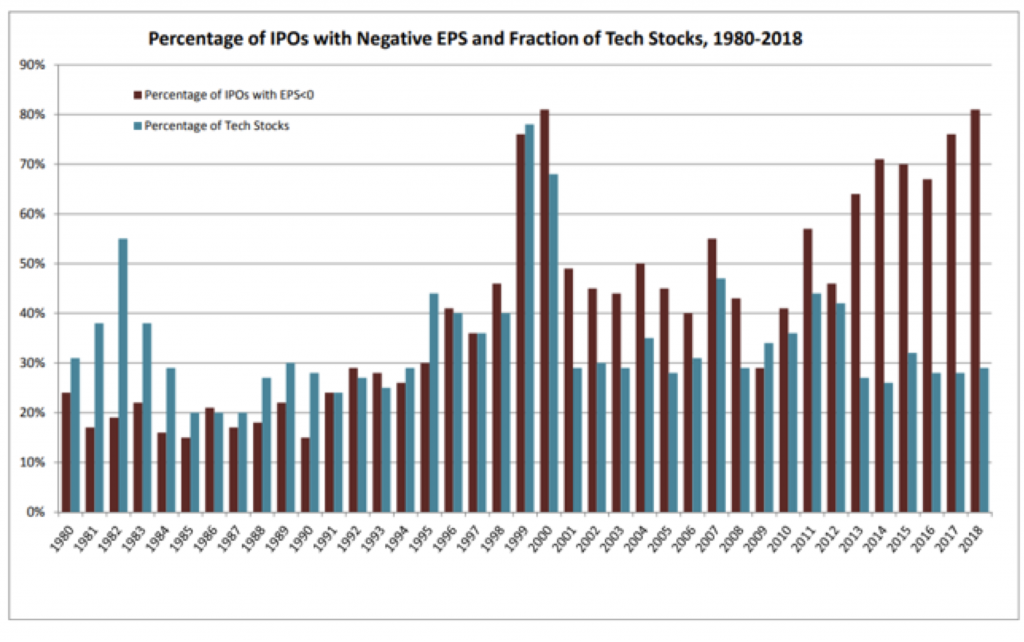

As the following chart illustrates, while the absolute number of loss-making companies listing on the market has now exceeded 80 per cent – the level reached prior to the Tech Wreck of 2000 – the percentage of tech stocks is materially lower.

I would hazard a guess however that if the chart’s author, Professor Ritter of the University of Florida, weighted each float for size, the percentage of ‘tech’ would be higher. A single Uber IPO at US$75 billion is going to have a material influence of the percentage of money funding these IPOs and therefore will look more like 1999/2000.

A picture tells a thousand words

Source: Prof. Jay R. Ritter, University of Florida

For what it is worth, I firmly believe we are in a white-hot bubble for technology start-ups and stocks. Private equity ‘valuations’ are absurd, with some, like DoorDash, rising from US$1 billion to $US12.6 billion in just over 12 months. That isn’t normal, nor is it sustainable.

Remember Herb Stein in these circumstances; “If something cannot go on forever, it must stop”.

More concerning is that just as the conga-line of loss-making IPO’s reaches a crescendo, the returns for mum and dad investors buying them on the first day has turned negative. According to Pitchbook, returns for all US$ 1 billion plus IPO’s purchased on the first trade as a listed company, produced a negative return. Negative feedback loops can quickly form, where retail investors zip up their wallets leaving the IPOs floundering and requiring more funding from the PE owners.

Experience tells me the only way to rescue the situation would be for private equity owners to leave some money on the table so that retail investors, those who buy in after listing, can make a profit and be encouraged to support the exit of the smart money (tongue firmly in cheek).

To achieve that however the PE owners would need to lower their exit prices. Because of the ridiculous valuations paid in the last funding rounds prior to exit, there will be a reluctance to lose money.

And so, the trap is set.

Uber’s float is an example of what happens. The final IPO price was no higher than the valuation agreed at the last funding round, and at US$75 billion was well below the US$120 billion being touted in December last year.

What the smart money does at the beginning, the dumb money does at the end.

Like the recent housing bubble we warned you about here at the blog over two or three years, this tech bubble will end painfully and abruptly. To be clear, I am not suggesting this Tech Bubble is precisely like the one I experienced first-hand in 1999. In 1999 the fuel was simply the hope that e-commerce companies would find a way to generate revenue from the eye-balls visiting their sites.

Today’s bubble is a little different. Many of the tech companies being bid up to exospheric[1] levels do indeed generate billions in collective revenue. Monetization hasn’t been the problem. It requires hard work and billions of dollars of investment but many of today’s cat walk of tech companies have achieved monetisation. This time around, the hope is that tech companies will be able to reduce costs and increase the scale of their operations such that profits will eventually be extracted.

Perhaps the difference is only subtle. Where the two bubbles are identical is that investors are once again betting on hope rather than reality.

[1]Exosphere: The upper layer of our atmosphere, where atoms and molecules escape into space.