Diving a bit deeper into the Australian property market

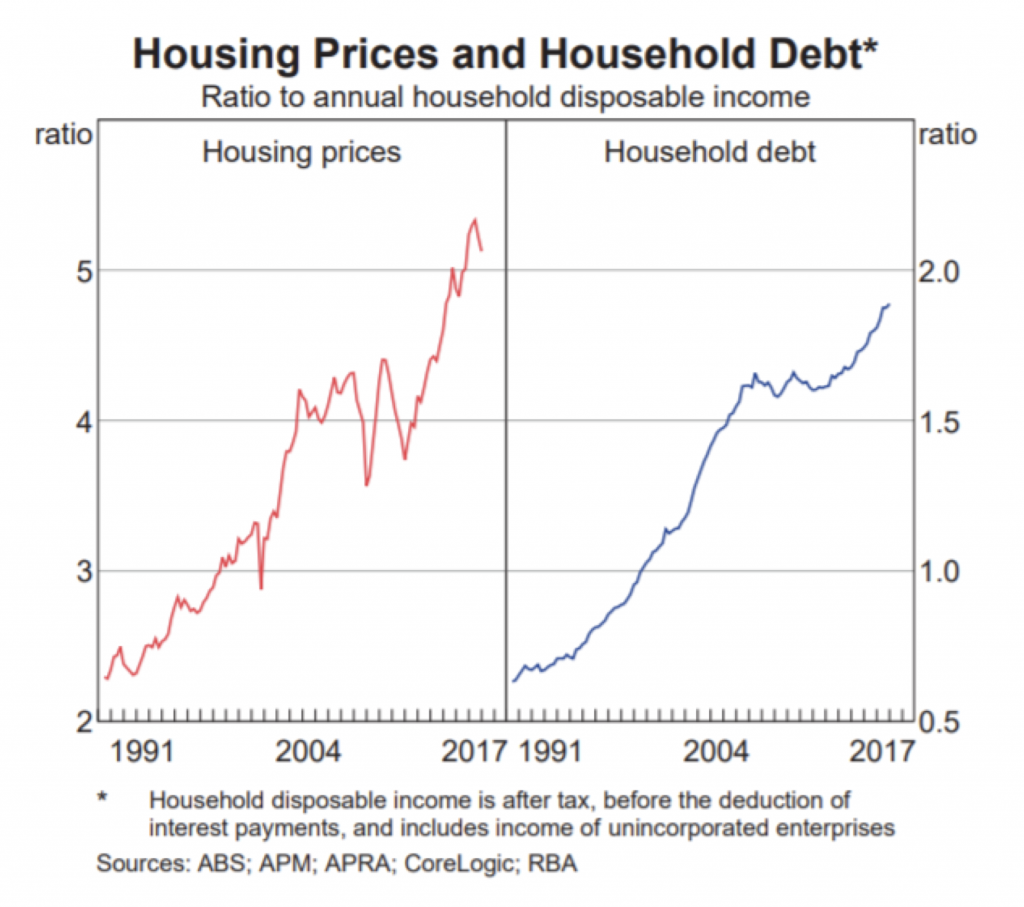

One of the significant issues currently facing investors in the Australian equity market is the possible trajectory of the residential property market. With property prices having risen to historic highs and household balance sheets having expanded sharply to keep up, the expression ‘primed’ is one that springs to mind.

Historically, large declines in the Australian property market are rare beasts, and the baseline probability for such an event is correspondingly low. However, more recently, some alarming findings from the Financial Services Royal Commission and the observation of a softening property market has prompted many to ask if the catalyst for a change might now be to hand. Given the scale of the residential property market and the widespread nature of possible flow-on effects, it certainly makes sense to consider potential scenarios.

With this in mind, we have been at work putting together a simulation model that aims to capture the important features of the property landscape; things like: the distribution of household incomes, household wealth, expenditures, borrowing propensities, property prices and ownership. With a reasonable approximation of the relevant features we should be able to better understand the possible implications of changes to parameters like credit availability, interest rates and prices.

This work is fiddly, and is still at a preliminary stage. Getting data from a variety of different sources to reconcile is surprisingly challenging. Even getting a clear read on things as basic as mean property prices and mean disposable incomes (as needed to plot the chart above) is harder than you might think, and there are many assumptions and approximations that need to be incorporated, so even a fully developed analysis needs to be taken as indicative only.

Nonetheless, we think the work is starting at least to raise some interesting questions. One of the simple parameters we thought might be helpful to estimate is the percentage of Australian households that have the financial capacity to buy the median Australian property without needing to sell existing property or other assets. Using this as a metric, we thought we might assess the impact of different changes to credit availability.

What surprised us, however, is the very low percentage of households that our analysis indicated could actually buy the marginal property on this basis. As it stands, we think the percentage may be below 10 per cent.

The driver, of course, is high property prices, but it’s a bit more subtle than that. Our modelling suggests that a sharp decline in property prices today would not necessarily do much to increase the proportion of households who could manage this acquisition.

The reason for this is that, having already bought property in the last 5-10 years at elevated prices, Australian households today generally appear to have little incremental capacity to take on new debt. The thing that would fix this problem is if the price rises that occurred over the past decade had never happened.

It appears as though the horse may have bolted here.

While it is only a preliminary view, this finding may shed some light on the low turnover levels currently being seen in the market, as well as possible scenarios for further growth in credit and prices. A lot more work is needed to arrive at a more concrete view, but in the meantime a prudent investor may wish to ensure they know how many seats are between them and the exit aisle.

One of the significant issues currently facing investors in the Australian equity market is the possible trajectory of the residential property market. Share on X

Being a West Australian, whose market is at multi year lows currently, I do find these articles stating the “Australian market” as puzzling. Housing affordability is the best it’s been in years, so good news for first home buyers and those game to invest given our resource driven economy is starting to show a degree of positivity.

It’s a big country, with various economic cycles in play.

That’s because generally speaking, nowhere else outside of Sydney, Melbourne (and occasionally Brisbane) gets a mention on issues like this…an example of this was ten years ago at the height of the resources boom, when you saw Perth being included on the list of things that people in Sydney and Melbourne take as a given (examples being the seminars provided by various SMSF providers and fund advisors, or that particular airline lounges were being upgraded)…prior to that, no one seemed to care.

So, when people talk about ‘a boom’ in prices, I look around and say “Where ? Certainly not in WA or SA !”. Interstate investors might be looking there and going “oh, look what I can buy with Sydney dollars, that’s cheap there”, but good luck getting finance approval now.

maybe, but if Sydney and Melbourne crash Perth is probably going to fall even further – arguably it is only the end of the resources boom that has popped the outer layer of the bubble, that bubble is sitting on top of an a much bigger one that when it goes is going to effect all Aus markets.

Good point Paul, and what I find equally puzzling is why more people don’t complain about the two speed property markets in this country.

If you live in Perth or any other regional commodity producing areas, your property prices are at the mercy of the direction of these markets, and understandably so.

But if you live in Sydney, Melbourne, or Brisbane, you property’s value will be artificially elevated due to the governments centrally planned immigration ponzi economy, that only benefits these areas where immigration is concentrated.

Yet the entire population will be equally forced to foot the bill for infrastructure and services expansion to support the ponzi.

While regional areas receive little or no benefit. Maybe a tax deduction for regional post codes would even things up a bit.

Thank you Tim. May I ask, what is your base case for residential property over the next 5 years?

Hi Tim, I would say it’s far worse than what your analysis shows due to as you say, it’s very challenging to get data on it, and that’s because this whole industry is full of snake oil from one end to the other, it’s an entire scam, the data is juiced and goosed by those who have an interest in Keeping prices high, one example is not reporting sales that don’t quite meet expectations to keep the average prices higher, and I’ve noticed that banks are holding on to foreclosed properties for years hoping to get redicules prices advertised, even long after they were passed in at auction.

The massive scam has many parasites that feed from it, they range from the agency’s and the media through many retailers and the government it self which would be bankrupted without sucking out all that stamp duty from the so called investors. All these parasites do their bit to keep the beast alive, but shes starting to look quite anemic and a bit wobbly in the legs now.

Has this analysis changed your thesis on the Montgomery Fund’s REA investment despite knowing that the longer properties are listed on REA the more money they make. Thanks.

Our thesis sees improving turnover as an upside case rather than a base case, so the analysis is relevant, but doesn’t necessarily change our base case.

It would be interesting to combine this analysis with your other excellent articles on behavioural economics – specifically the phenomenon of “loss aversion”. What we are looking for is not just a scenario where the average property investor gets under water, but the scenario(s) where they are forced to realize whatever losses they are carrying. Commercial capital like a bank has to get a return on their capital which means in commercial property slumps they just sell up and go on to something else. The average little Oz property investor is not a “rational capitalist” in that sense, and may well just hang on.

Another way to look at is is this: the central belief of such small investors is “house prices double every seven years”, which through the great bubble of the last 2 decades has been more-or-less true. Surely such people will want to wait seven years to see that it has stopped and then, maybe, another seven years just to be sure… and maybe another seven for good luck…

Agreed.

Those people who bought in Moranbah will be waiting a long time though, and a 50% loss means that it needs to go up 100% to break even again.

Most property investors also don’t take into account the money spent on upkeep, holding costs, negative gearing, CGT, overcapitalising on renovations, interest payments etc., instead, claiming that they bought somewhere for $300k and sold it however many years later for $800k, thus “making a profit of $500k”. Their real return is much lower, but it sounds better at a BBQ to talk about they flipped a house and made money.

Tim,

Do you mean that the 90% of households could not afford to buy a median home outright, o,

do you mean that 90% of households could not access enough credit to afford to buy a median home?

Best John

Hi John. We apply both tests. We assume the household can access debt, but to an extent constrained by its disposable income.

We also assume no sale of other household assets, which,if relaxed, would increase the number of eligible households.

Well if that is the case 10% of households able to buy represents a very very low demand. I guess the real test is to run this test over different historical time points and see what the change is.