The end of “old school” value investing?

Students of value investing will know that in past times, value investors paid great attention to accounting book values. One of the better-known strategies employed by the spiritual father of value investing, Ben Graham, was to try to acquire companies at market prices that were below their conservatively-estimated liquidation value.

This was not a strategy for the timid – companies that found themselves in this position frequently did go into liquidation. However, a diversified portfolio of companies that fitted this description could do well on average.

Over time, the proportion of listed companies that meet Graham’s rather strict criteria has declined to the point where building a diversified portfolio of them has become tricky. However, the ratio of book value to market price has become well-embedded in the canon of value investing, and it continues to be used by many investors to screen ideas. This approach has been further supported by academic studies that show that…well, it works.

Or does it? As time moves on it, is it worth thinking about whether changes to the underlying structure of economies and equity markets may have eroded the usefulness of the book-to-price ratio. In the US, for example, the largest listed companies today include the likes of Apple, Microsoft and Google. These are businesses that owe their success less to hard assets and more to technology, innovation and brands. In developed economies, the Industrial Age has passed, and the Information Age is very much here.

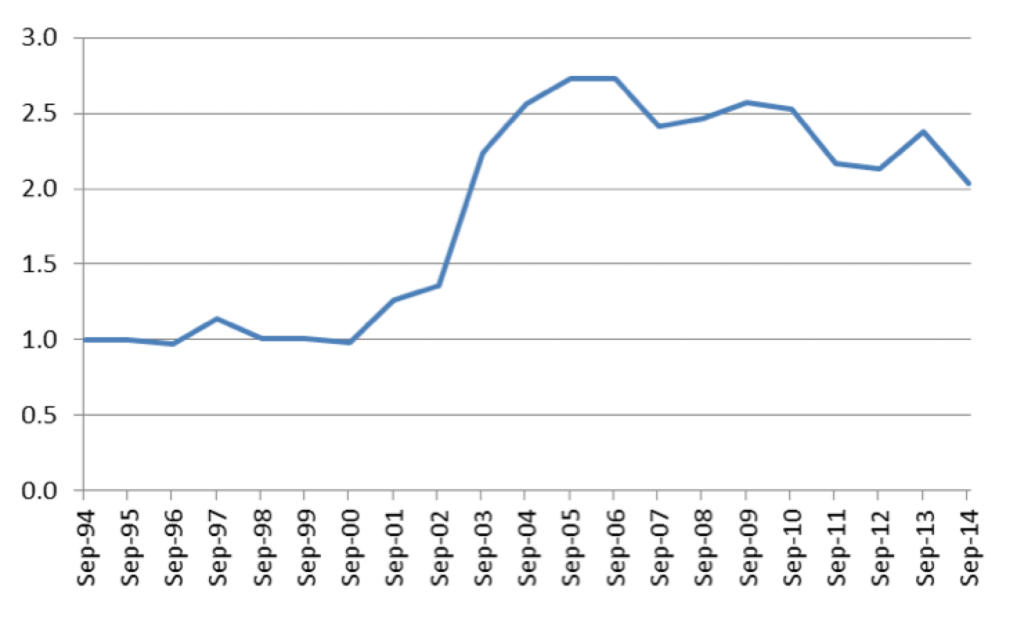

We thought we’d look to the data for some guidance, and did some analysis on the US equity market. To summarise, we looked at the returns an investor might have achieved over the last 20 years by investing in an equally-weighted portfolio comprising the top 20 per cent of companies in the Russell 3000 Index, based on their book-to-price ratios, and rebalancing every year.

The results are shown below. Note that the chart measures risk-adjusted outperformance, so anything above “1” indicates that the portfolio is beating the index. What the analysis tells us is that our hypothetical portfolio has indeed delivered outperformance over this period. We estimate a compound 3.6 per cent per annum of outperformance before costs, which is not to be sneezed at.

However, there’s a catch. All that outperformance was delivered during a short period in the early 2000s. For the last 8 or 9 years, the strategy has actually gone backwards.

Analysis of the Australian market tells a similar story – in recent years, book-to-price does not look to have done investors any favours.

Our analysis may not agree with the results found by others, and it may be that the negative trend we have found will turn around in years to come. However, if book-to-price forms part of your investment approach, it may be worth thinking about how confident (and patient) you are. To us, it feels like the world may have moved on.

Agree Tim that book value on its own is not a useful valuation metric – it does form the part of the valuation formula I use, but I’d consider ROE the most important metric. No single metric is useful on its own though, it’s important to consider all part of the business’ balance sheet, cash flow and profit/loss statements – not to mention the qualitative aspects.

Investing on a Price / Book ratio only seems a bit pointless, unless you consider the sustainable return on equity, then it can perhaps be a rather useful metric?