Lessons from past technology booms

Debt nuances

I just read the following sentence: “Graphic Processing Unit (GPU) rich clouds are now raising multi-billion-dollar debt with GPUs as collateral.”

It got me thinking…

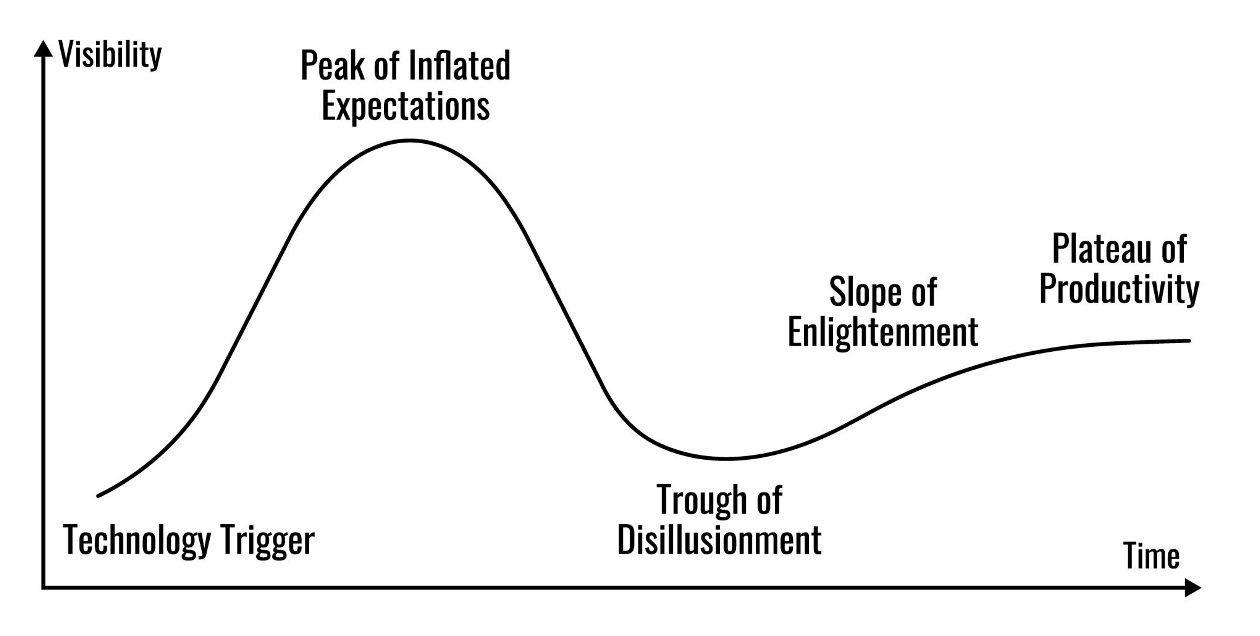

Figure 1. General Purpose Technology (GPT) booms and busts, Gartner’s hype cycle

Source: Gartner

In the railroad boom of the 1800s, U.S. railroad corporations issued bonds on everything – on their equipment, on their track, on their land grants from the federal government, and even on future profits. Today, that debt is being raised with GPUs as collateral – which is something that should cause us to sit up and take notice.

Much more recently, Bloomberg and PitchBook have variously reported that CoreWeave’s total GPU-backed debt has exceeded US$10 billion, Fluidstack (now a part of CoreWeave) received approval for over US$10 billion in financing using its Nvidia GPUs as collateral, Lambda secured a $500 million loan backed by its existing Nvidia chips, and Crusoe (formerly Crusoe Energy) has taken on hundreds of millions in GPU-backed debt, including a US$200 million deal in late 2023 and another US$225 million this year.

The Railroad bubbles and busts of 1873 and 1893, each demonstrated unsustainable growth and speculative lending that weakened the financial system and were major factors in the subsequent economic depressions, partly because the railroads were built on mountains of debt.

Today’s artificial intelligence (AI) buildout and data centre construction has hitherto been financed by the free cash flows and cash balances of the major U.S. technology companies, and with private capital from Private Equity firms like Apollo and Blackstone.

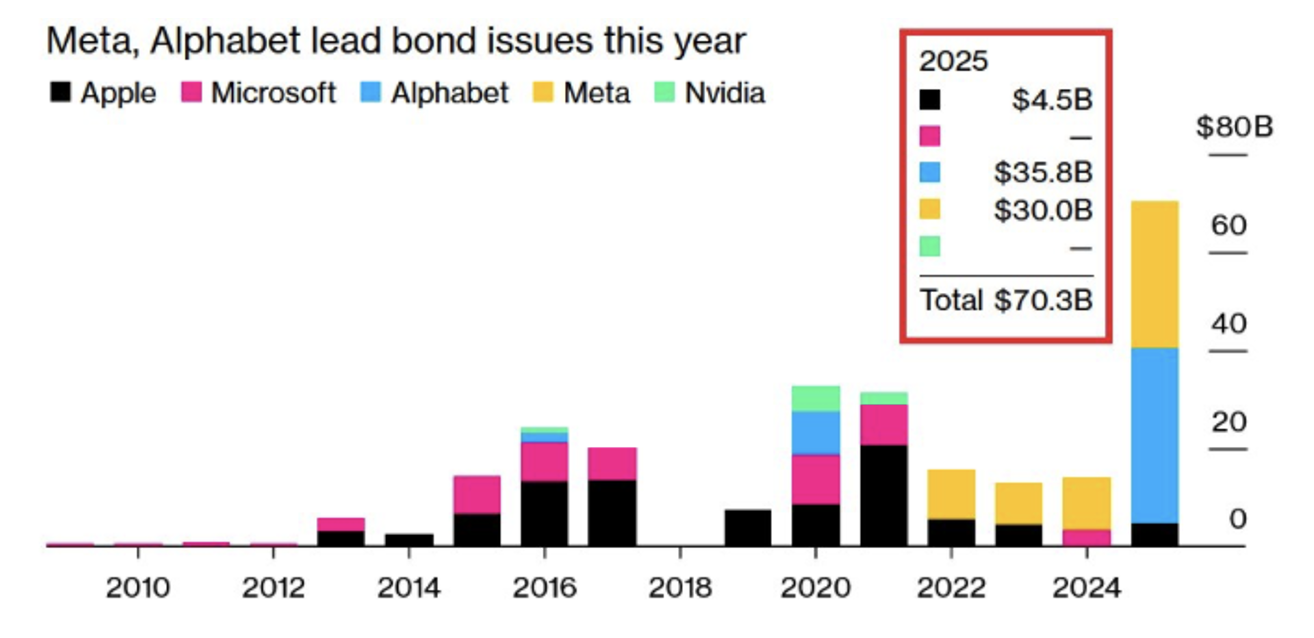

But changes are afoot. Back in October, Bank of America Global Research noted; “borrowing to fund AI datacentre spending exploded in September and so far in October.”

Figure 2. AI taking on more debt

Source: Bloomberg

Doug O’Laughlin, in his Fabricated Knowledge newsletter, wrote, “The implications are profound,” adding, “What had been a disciplined, cashflow-funded race may now turn into a debt-fueled arms race.” In subsequent interviews, O’Laughlin has said this ‘debt bomb’ is the sort of thing that should make folks worry that AI could be a bubble.

And the jump in debt illustrated in Figure 2., doesn’t account for the shift in AI spending off the balance sheets of the major hyperscalers.

Some are collaborating with private capital firms to form joint ventures called Special Purpose Vehicles (or SPVs), to fund datacentres and chips, with the expenditure and debt kept off the books. In June, Meta raised about US$29 billion from private credit firms for new AI data centres organised through such SPVs.

The Pied Piper: CoreWeave

I should note that Meta’s deal isn’t unique. AI cloud provider, compute seller, and non-consumer-facing company CoreWeave has been called AI’s ticking time bomb. Even though the company’s customers include Microsoft, OpenAI, and Meta, and its third-quarter revenues doubled to US$1.4 billion from the same period last year, The Verge’s Elizabeth Lopatto reported last month, “CoreWeave is saddled with massive debt and, except in the absolute best-case scenario of fast AI adoption, has no obvious path toward profitability.”

CoreWeave IPO’d (initial public offering) in March at a share price of US$40. In June, its shares peaked at US$187. Today, the shares trade at US$90.66. You might argue the bubble has already burst, but before you do… at the time of writing (10th of December 2025), CoreWeave has just upsized a private 2031 senior convertible note offering from US$2 billion to US$2.25 billion, carrying a 1.75 per cent interest rate payable semiannually and a conversion price of US$107.80 per share, which represents a 19 per cent premium over CoreWeave’s current price, suggesting there might be no bubble at all.

Lopatto also noted, “CoreWeave simply isn’t possible without Nvidia. The company said it owned more than 250,000 Nvidia chips, the infrastructure necessary to run AI models, in documents CoreWeave filed for its initial public offering (IPO). It also said it only had Nvidia chips. On top of that, Nvidia is a major investor in CoreWeave, and owned about $4 billion worth of shares as of August. Nvidia made the March IPO possible, according to CNBC: “when there was lackluster demand for CoreWeave’s shares, Nvidia swooped in and bought shares. Also, Nvidia has promised to buy any excess capacity that CoreWeave customers don’t use.”

And that makes its debt even more eyewatering.

Debt facilitated by backscratching?

Meanwhile, Nvidia and OpenAI have signed a partnership agreement to deploy circa 10 GW of Nvidia systems, with Nvidia intending to invest up to US$100 billion as deployments progress. Elsewhere, Microsoft’s OpenAI tie-up includes very large Azure commit/usage, so OpenAI’s Azure consumption contributes to Microsoft’s reported revenue.

And in case you’re wondering, no, “These investments are not circular; they are complementary.” That’s what Lia Davis, CoreWeave’s head of global communications, said, adding, “This is about an entire ecosystem all rowing in the same direction to accelerate the AI economy. There’s nothing circular about it. Rather, these partnerships are about accelerating innovation and adoption. We are, collectively, defining the next-generation operating system for civilization.”

Investors have been delivered this line before.

U.S. railroads were similarly “central” to advancing civilisation at the time, shortening a trip across America that took 12 weeks in 1800 to just three days by 1930. But railroads were so ‘central’ in the second half of the 19th century that they regularly caused bubbles and busts.

AI is being described as similarly “eating the economy”. Seventy-five per cent of the S&P 500’s returns since ChatGPT was launched can be attributed to AI-related stocks, while datacentre construction spending is eclipsing other construction while also causing electricity prices to spike across the country.

Richard White wrote in his epic history of the U.S. railroad companies – the ‘transcontinentals’, Railroaded, “they created modernity…” But they also left behind “a legacy of bankruptcies, two depressions, environmental harm, financial crises, and social upheaval.”

It would be unusual if this time is different

It might be worth remembering the words of journo Derek Thompson, who wrote in his 4 November newsletter, AI Could Be the Railroad of the 21st Century. Brace Yourself, “Memories are short, and prudence and natural risk aversion are no match for the dream of getting rich on the back of a revolutionary technology that “everyone knows” will change the world.

The global railway mania of the 1800s bankrupted thousands of investors, wiped out hundreds of companies, but left nations with a rail network that powered a century of industrial dominance. Similarly, when the fibre-optics/internet/broadband boom of 1999 crashed in early 2000, it vaporised $US5 trillion of market value, but it also laid the wiring on which Internet Age began. Similar stores can be told about the electricity bubble, aviation, broadcast radio and automobiles.

Indeed, about three-quarters of General-Purpose-Technology (GPT) booms share a similar pattern of colossal over-investment, financial carnage through creative destruction, then lower prices and decades of productivity gains assembled on the residual infrastructure.

At the core of today’s AI boom are General Purpose Technologies (GPTs) – on the scale of electricity or the internet – and the infrastructure being built will support decades of economic activity. And unlike the Dot.Com bubble, the investment isn’t billions in speculative debt being loaned to ‘pre-revenue’ companies with no path to profitability. This time, the investment is coming (so far) mostly from companies with strong balance sheets. But beyond that core, the classic signs of every bubble are on display.

It would be unusual, given the great enthusiasm or hype, the high asset prices, the overbuilding, the uncertainty of future demand, indeed, the many elements that conform to past bubbles, if this boom doesn’t also conform to the pattern illustrated in Figure 1. It would indeed be a first.

However, if so many people think we are in a bubble, can we really be in one? I would answer by pointing out bubbles aren’t black swans.

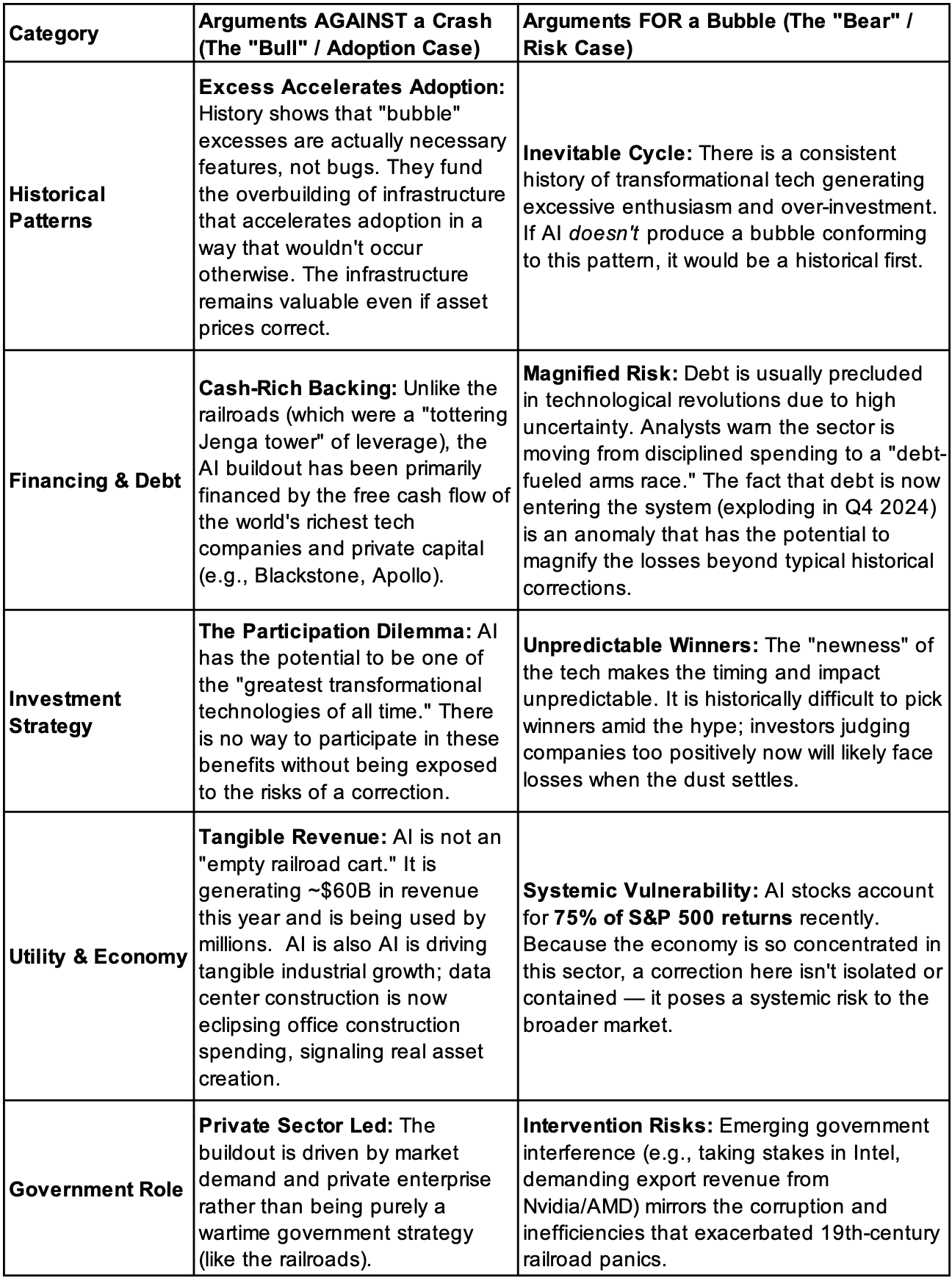

Table 1. Bulls versus Bears

Whatever side of the debate you sit, Table 1., is my attempt to summarise some of the arguments for the bulls and bears.

Do you think the current debt-fuelled race is sustainable if AI adoption slows even slightly?

No I don’t.