If you are an income investor, it pays to think long-term

The past year has seen a distinct switch in investor focus from growth to yield. The irony, of course, is that many so-called ‘dividend stocks’ can be long-term wealth killers. And that’s why we prefer quality businesses – like CSL – which can grow both their market value, and their dividends, over time.

With all the talk of rising rates, I am hearing a great deal of discussion about building a ‘dividend portfolio’. Many years ago, I wrote about dividends, dismissing the flawed search for yield and replacing it with something far more valuable – rapid earnings growth.

Written between 2010 and 2015, those articles and blogs are buried deep, making their discovery unlikely. But their lessons are timeless, and so it’s worth reprising them today and updating them for 2023.

Many of the columns I have seen discussing dividends, income portfolios and yield, fail to address the critical arithmetic that can produce the proper framework for thinking about constructing the best portfolio.

So, reprised from the 2015 archives, here’s what you need to know, noting I have updated one of the tables to today’s date, which demonstrates the timelessness of the lessons therein:

“We have previously written about the bubble in stocks (and inevitably property) inflated by the baby boomer’s desperate search for yield. We described the pursuit of yield as a fad. So, while we were not surprised to watch investors rushing into higher-yielding banks and Telstra, we were shocked to hear of investors buying BHP for its ‘progressive’ dividend.

The bubble has burst, but the fad lives on, and banks have wiped billions from retirees’ wealth while BHP has backed away from its ‘progressive’ dividend position. We wrote:

“The pursuit of yields through dividend-paying shares is analogous to a mindless herd of bison stampeding towards a cliff. Wall Street will sell what Wall Street can sell. Right now selling yield and income is the easiest game in town. Investors are predisposed to hearing the siren song of income and advisers and product issuers are rushing to feed the hoards. There are only a few who are willing to question the conventional thinking about pursuing yield at all costs.

My belief is that the pendulum will swing back and this time is no different to other periods of unbridled optimism…”

Of course, much has changed, but what has not changed is retirees’ need for income. But is there a better way to generate income that suffers less from the massive tides associated with mass investor hype and hysteria?

High payouts may generate income but limit growth

I believe some basic arithmetic can demonstrate a superior choice, even for those requiring income.

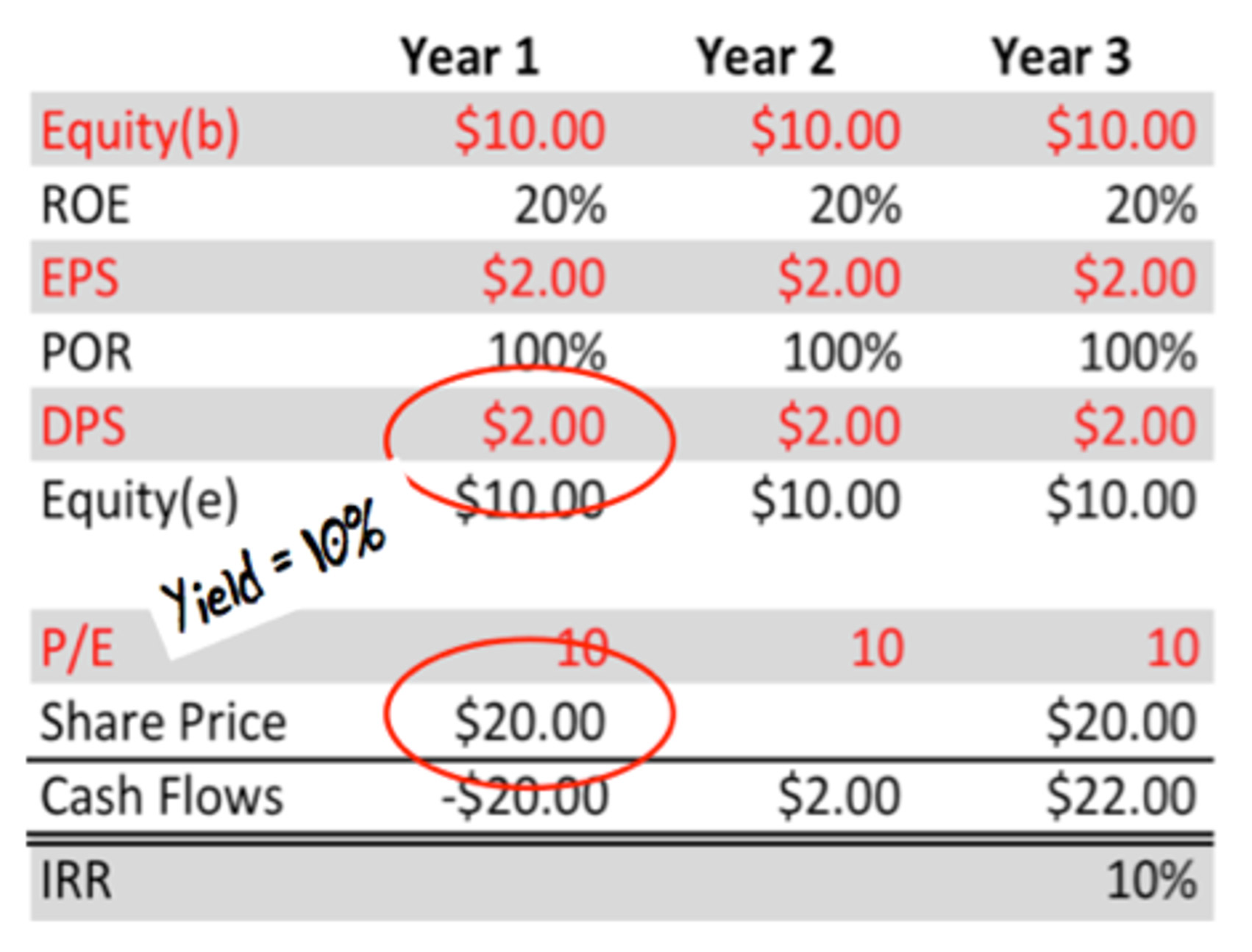

Table 1. High return on equity (ROE) company paying out 100 per cent of earnings

Let’s start with the company described in Table 1 by making some minor assumptions. First, we assume the business is able to generate a ROE of 20 per cent sustainably. Second, we can buy and sell the shares on an unchanged price earnings (P/E) ratio of 10 times. The final assumption is a payout ratio of 100 per cent.

We have assumed no increases in debt (which increases the risks) and no dilutionary share issues. The company’s only source of growing equity is retained profits.

Table 1 demonstrates that an investor who purchases and sells shares in a company with an attractive rate of return on equity, a constant P/E and a payout of 100 per cent will receive as their return an internal rate equivalent to the dividend yield at the time the shares are purchased. This represents the upper bound of their return – the dividend yield is the best outcome, unless they speculate successfully on an expansion of the P/E ratio. For that to occur, sentiment or popularity towards the company’s shares would have to change and be correctly predicted.

In more simple terms, if you chase a high yield and the company pays all of its earnings out as a dividend, the high yield is about all you should expect. Perhaps that is what investors who chased the banks, Telstra and BHP are now finding out.

Lower payout ratios can improve total returns

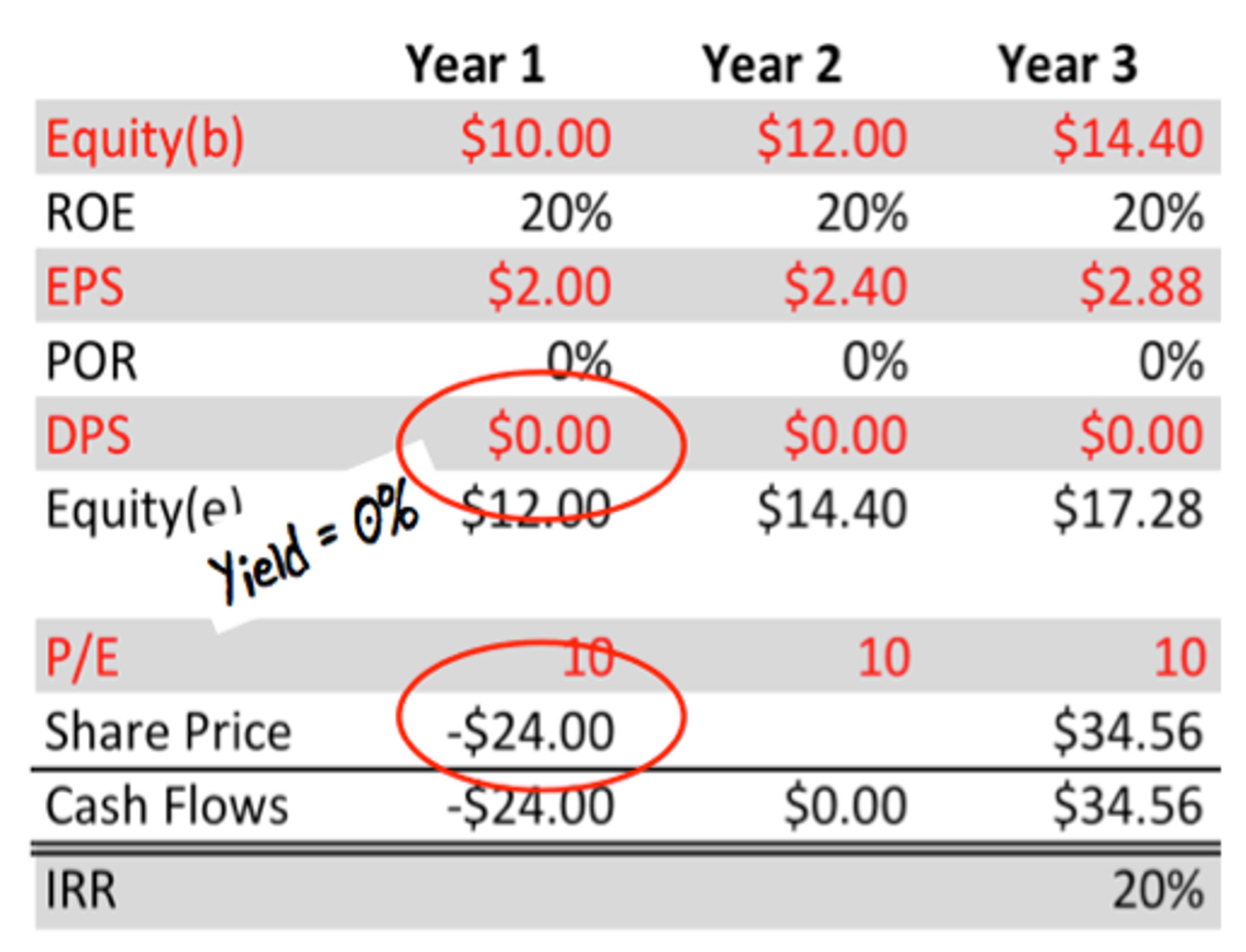

In Table 2, the only item that has changed is the payout ratio, which is now zero. Of course, this has a major impact on everything else.

Table 2. High ROE company paying out zero per cent of earnings

This company pays none of its earnings out as a dividend. An investor who buys and sells the shares on the same P/E ratio will experience capital and earnings growing by the rate of the retained ROE. The constant P/E ratio means the IRR to the investor will equal the return on equity of 20 per cent.

My proposal is that investors who chase higher yields, especially from companies that pay the bulk of their earnings out as dividends, are missing out on major financial benefits. The corollary is that company boards who acquiesce to shareholder demands for higher dividend payout ratios – especially where they are able to employ retained earnings at high rates of return – are ultimately doing their shareholders and their share price a disservice, as shown in Table 3.

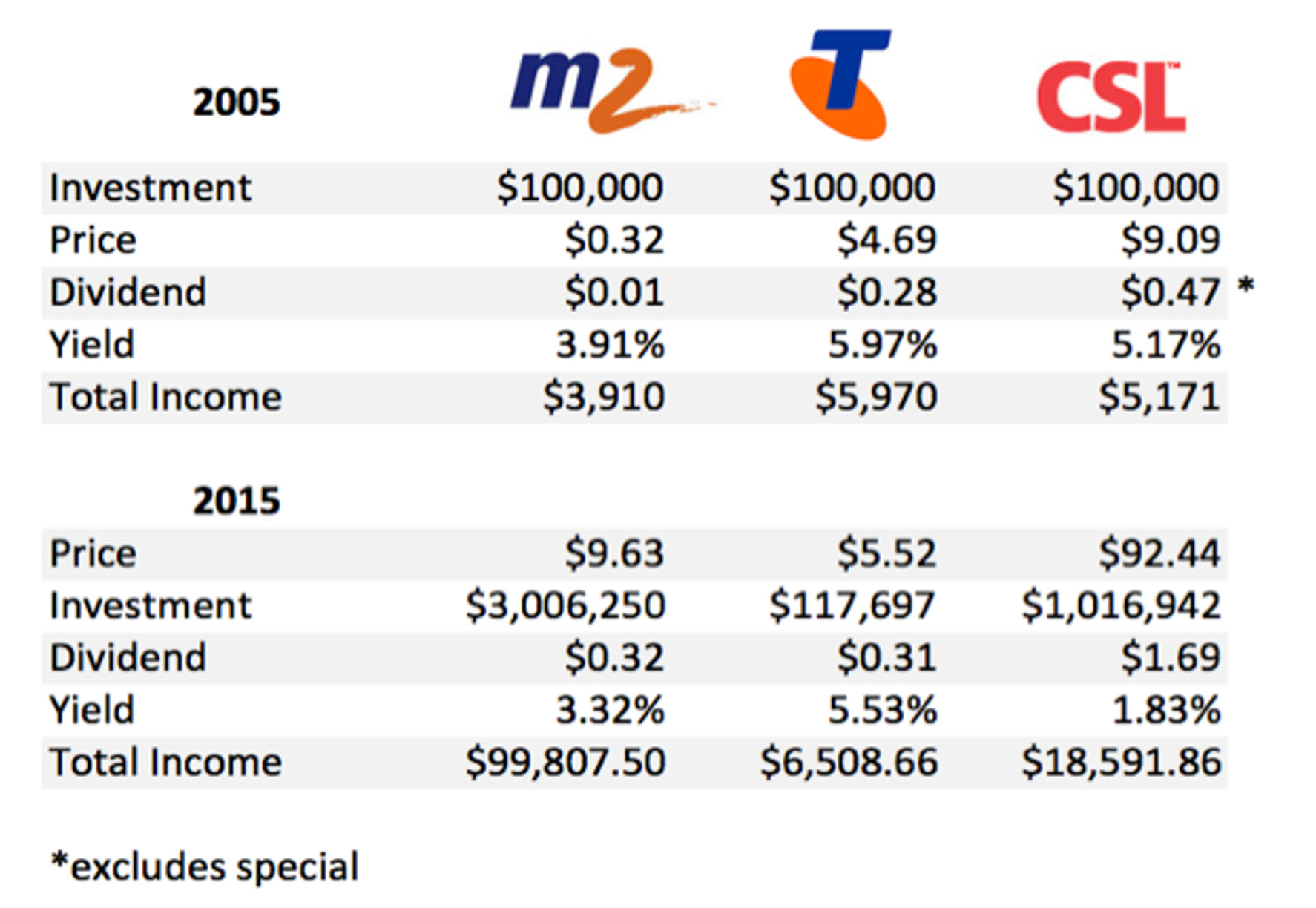

Table 3. Power of true blue-chips

It’s not only about dividend yields

Investors in 2005 who invested $100,000 in the higher, 5.9 percent-yielding Telstra shares could have invested $100,000 in the M2 Group. The major difference between these two companies was not just their yield. Telstra’s management elected to pay the bulk of the company’s earnings out as a dividend. Indeed, under Solomon Dennis Trujillo, Telstra’s dividend exceeded earnings over a number of years. While Telstra’s payout ratio was near 100 per cent, M2 Group’s payout ratio was much lower. Table 2., reveals the desirable impact on returns from investing in a company that can retain earnings and reinvest those earnings at a high ROE. Table 3. puts that into practice.

Investing $100,000 in Telstra in 2005 for ten years has produced an investment of about $117,000 or an average annual compounded capital return of 1.5 per cent p.a. Many of you will jump to the defence of Telstra and point out that I have excluded the dividends from the calculations. But this article is about retirees who have been chasing income to spend on food and clothing and other essentials, so I have not assumed reinvestment of dividends.

In 2005, the 5.9 per cent yield on Telstra shares equated to $5,900 of fully franked income. Telstra has increased the dividend since then from 28 cents to 30 cents per share and the low increase reflects the fact that profits have not grown markedly. In any event, the income on the $117,000 investment would be about $6,500.

Contrast this with M2, where the ability to generate high returns on large amounts of capital have turned $100,000 into $3 million and, importantly for those desperate for income, turned $3,900 of dividends in 2005 into almost $100,000 of fully franked dividends in 2015.

M2 is not an isolated example of the power of high rates of return on equity and the ability to retain profits. For example, CSL also displayed a less attractive dividend yield than Telstra in 2005, but was able to retain capital and compound it at an attractive rate, ultimately producing more wealth and income.

Investors chasing the highest-yielding blue-chip shares are missing out on the returns and income available from true blue chips – the type we prefer to fill our portfolios with. Investors are making an expensive mistake by eschewing those companies with lower yields today but able to grow their income. Go for growing income, not the highest yield.

To demonstrate the timelessness of the lesson, I wanted to bring Table 3. up to date for 2023, noting M2 Telecommunications merged with Vocus communications on 28 September 2015 and is therefore removed.

Table 4. Don’t chase yield. The Power of Bluechips

As Table 4., demonstrates, the lessons learned in 2015, if applied since, have produced an unsurprisingly similar outcome. CSL has been growing its earnings, from which growing dividends have been paid. This growing income stream makes the company more valuable to investors who are understandably willing to pay more, driving the share price higher and adding to the investor’s reward for selecting a superior investment.

The lesson is, if you want income, go for growth.

The Montgomery Fund own shares in CSL, Telstra, National Australia Bank and BHP. This article was prepared 21 February 2023 with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade these companies you should seek financial advice.

Roger, do you know what effect drawing down the difference between the amount of the Telstra dividend and the CSL dividend from the CSL investment each year would have?After all, the investor still needs the same amount of cashflow whether invested in a growth or dividend stock. What would the value of the CSL shares be after the 20 years in that scenario?

The drawdown would only be required until the amount of the CSL dividend equaled the Telstra dividend. How many years would that take?

Hi Roger

Yes , I have read Value.able and recommend it to all share Investors. I purchased your first Edition some years back which was autographed by you. I liked the Book so much that I read it twice – I can’t ever recall reading any other Book twice. The Book contains a lot of information which all makes sense, but at the end of the day it’s all still very much about buying at a bargain price ($1 for less than $1) and that is not always that easy to do.

Agree Max. That’s the ideal scenario. I have found, through painful experience, that waiting for the perfect price however can prove dangerous to your wealth. better to buy a wonderful company at a ‘rational’ price.

Hi Roger

A Dividend Growth strategy is worthwhile provided the Dividend Yield does not represent a payout ratio of 100% , which would not allow for any re-investment of earning for growth.

As I mentioned recently , I don’t mind Dividend paying stocks provided the yield is in the range of 3% to 4% (fully franked) – that ‘s a Grossed up yield of 4.3% to 5.7% (assuming a tax rate of 30%). Why leave all the franking credits locked up in the Company which has no use for them? Dividends and franking credits I think are the low hanging fruit which Investors should harvest provided the Company retains sufficient Earnings for growth. Growth in EPS should ideally be in line with GDP Growth rates but preferably higher.

In your article you talk about BHP. Did you know that in June 2003 you could have picked up BHP shares for about $7 and today they are trading at $48 – that’s almost a 600% Capital Gain over close to 20 Years and not to forget the generous grossed up fully franked Dividends that were paid out over that time.

So don’t assume all Dividend paying stocks don’t have a place in a portfolio – to succeed with them you have buy them at attractive valuations, but that applies to any Investment. “The price you pay determines your future return”. Would I buy BHP at $48 today? Most definitely not !

Thanks. Sounds like you’ve read Value.able!

Awesome!