Could deflation be the next surprise?

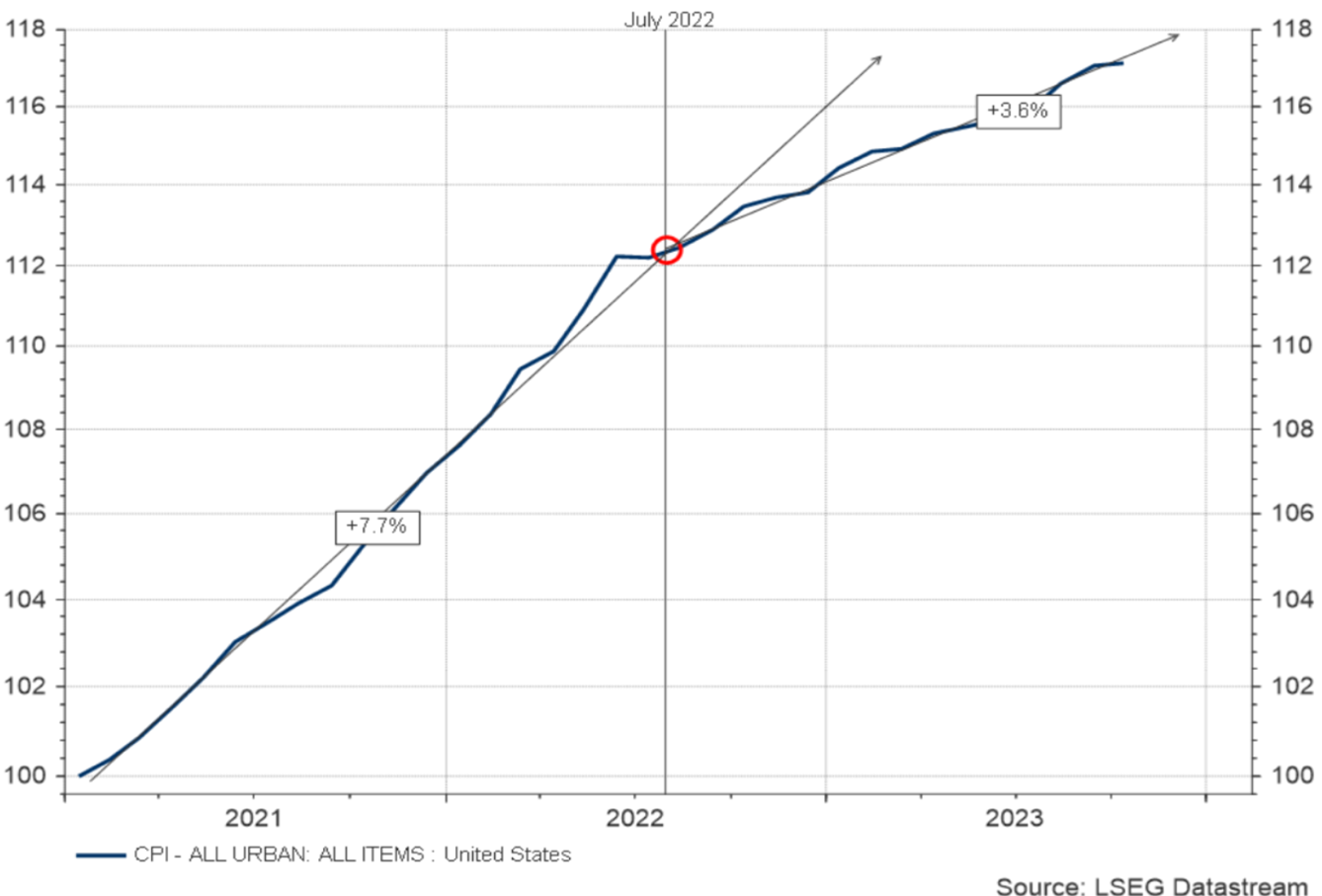

After the well-documented U.S. money printing spree of 2020-21, something interesting happened in the U.S.: Inflation started picking up in 2021-2022. Just as it takes time for water to fill a bucket, it took time for inflation to emerge, but when it did, annualised inflation averaged 7.7 per cent for 18 months from January 2021 to July 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. U.S. CPI Inflation trend (log scale)

But since July 2022, the pace of inflation has slowed, and over the past 15 months, the U.S. inflation rate has dropped by half to 3.6 per cent.

The consensus narrative seems to be that the easy inflation challenge – bringing inflation down from a peak of 9.1 per cent at the end of June 2022 to its current level – has been won. The task of bringing it down further to the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) target, however, will be more difficult. That view was reinforced recently when the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Chair, Jerome Powell, said, “we are not confident” the Fed has tightened enough to bring inflation down to its two per cent goal, adding officials would monitor economic conditions closely to avoid raising rates too high, but noting there is a risk of being “misled by a few good months of data.”

Here at the blog, we have written about Australia’s more persistent domestically driven inflation and the blunt instrument of monetary policy, which impacts people inequitably. Those who have mortgages and have reined in spending are hit again and harder when rates are raised. But the mortgage-free homeowners, those with cash in the bank, keep spending (and fuelling inflation) because higher interest rates flow through to higher earnings on their cash deposits.

Back in the U.S., and in October 2023, the most recent data shows Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation at 3.2 per cent. A few reasons for the drop include a slightly higher starting point and lower energy costs (which fell by 4.5 per cent).

This steadier inflation rate, which is almost double the Fed’s two per cent target, is happening alongside a tight job market and a strong gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 4.9 per cent (in the third quarter of 2023). All of this has many commentators and investors believing that we will have a kind of “sticky” inflation for a while. I confess that has been my conclusion from listening to the central bank commentary and observing the same data that informs their comments.

But what if there’s a valid alternative scenario? Rather than lower but sticky and persistent inflation combined with a soft landing, could we see deflation and a recession? It sounds extreme, but some think so.

The economists at UK-based Macro Strategy Partnership believe the lags associated with the implementation of U.S. monetary policy will trigger a recession and deflation.

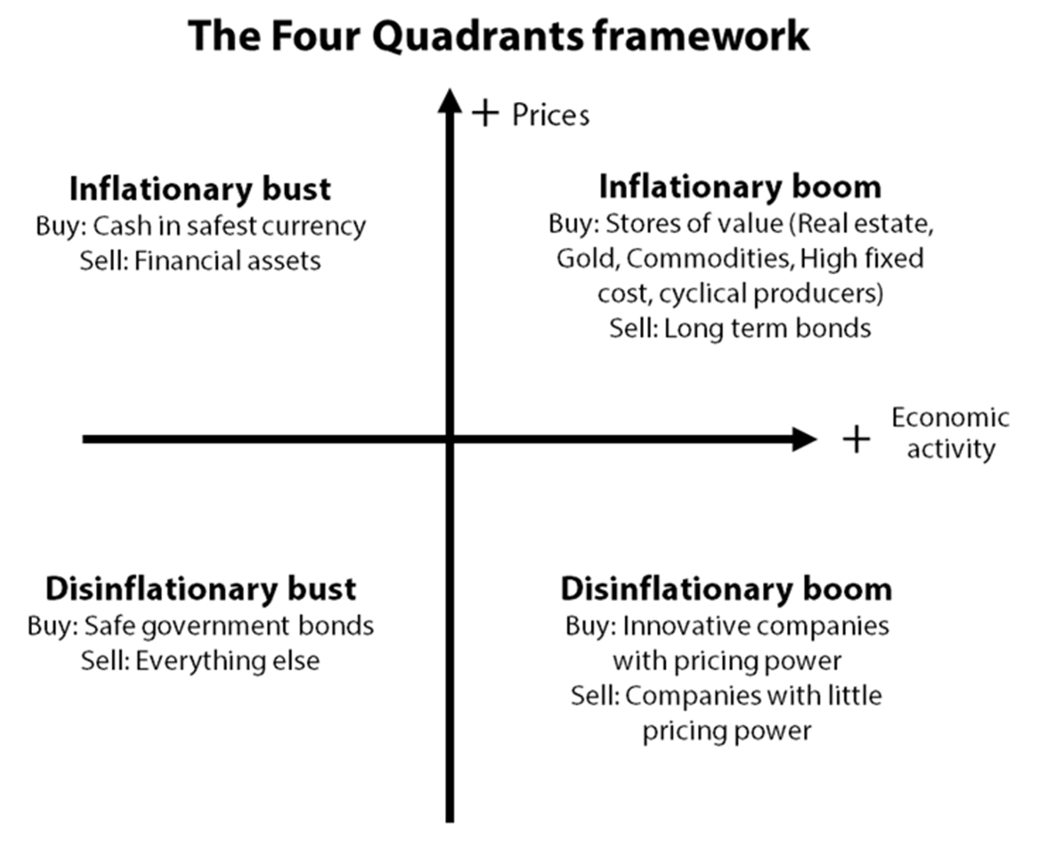

Before proceeding any further, it’s worth keeping in mind Gavekal Research’s Four Quadrants Framework in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Gavekal Research’s 1978 Four Quadrants Framework

First published in 1978 and given to me by fellow fund manager David Paradice in 2004, Figure 2., shows that disinflation, when combined with positive economic growth – referred to as a disinflationary boom is good for innovative companies with pricing power.

A ‘disinflationary boom’ has existed for all of 2023, and perhaps coincidentally, the best-performing stocks have been the Magnificent Seven, which includes Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, Nvidia and Tesla. Many of these companies have pricing power, and all of them are innovative.

However, disinflation is not deflation.

Disinflation can be described as consecutive prints of lower rates of inflation. In other words, prices are still increasing, but at a slower rate. The economy is experiencing a reduction in the pace of inflation.

Deflation, on the other hand, is a more severe economic condition characterised by a sustained and generalised decrease in the overall price level of goods and services in an economy. In a deflationary environment, prices are declining, which can lead to a variety of economic problems.

Deflation is problematic because when consumers expect prices to continue falling, they rationally delay spending and investors do likewise. Together, it can slow down economic activity. Additionally, and arguably more significantly, deflation increases the ‘real’ burden of debt, making it harder, or more expensive, in real terms for individuals and businesses to repay their loans.

Deflation is what the economists at Macro Strategy Partnerships and Cathie Wood of Ark Invest believe is barrelling down the highway towards investors in 2024.

Macro Strategy writes, “The typical 12-18 month lags between monetary policy and economic impact have meant that a data-dependent Fed was ultra-loose when it should have been tight (2020-21) and subsequently, ultra-tight when it should already have been neutral or even loose (2022-23)”, adding, “The post-lag implication is that rather than ‘sticky’ inflation and a soft landing, we should expect recession and potentially even deflation without an immediate and dramatic change in monetary policy direction.”

Macro Strategy believes the assumption of sticky inflation and a soft economic landing in the U.S. does not stand up to scrutiny despite the strong GDP and jobs market. They note the 8.5 per cent nominal GDP of the third quarter can be entirely explained by the ‘blowout’ government deficit, which was also 8.5 per cent of GDP. They point out that excluding the deficit, i.e. private sector GDP, “has basically been flat for a year, even in nominal terms.”

The UK-based economists believe the “deficit-funded goosing of the economy” explains why indicators, including Legal Entity Identifier’s (LEI), Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), yield curve, Gross Domestic Income (GDI), tax revenues, corporate profits, money supply, savings rate, intermodal rail, and home affordability, appear to be in recession. They also note that although manufacturing construction and GDP continue to surge, unemployment is now 3.9 per cent, up from 3.4 per cent in April to a new 21-month high.

With respect to their deflation argument, they note the housing component of U.S. CPI lags so far behind reality that it considerably distorts the inflation measure. The consensus view is that inflation remains ‘sticky’. However, if the shelter component is excluded, true inflation was initially far more pronounced, with double-digit trend growth in the 18 months following money printing, and now much slower, indeed below-target, and at a trend rate of just 1.2 per cent since July 2022.

That’s a big claim because it suggests the Fed is raising rates when, in fact, it should already be cutting rates.

Cathie Wood of Ark Invest has paid the price for bold bets on stocks that suffered as interest rates rose. The Ark Innovation ETF she manages lost 24 per cent and 67 per cent in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Her belief is that the economy and her funds will now benefit amid an AI-driven deflationary environment.

Wood also says that a 60 per cent decline in U.S. gas prices reflects a significant destruction of broader demand. Meanwhile, Wood notes the strength of the U.S. dollar will remain another deflationary force and will be sustained amid liquidity concerns in countries like China and Japan. Elsewhere in the U.S., Wood points to weakness in housing, auto sales and inventories.

Wood’s deflationary scenario also contemplates a hard economic landing. Speaking at a Forbes conference in October, Wood said, “We’re going to have a harder landing than most people expect – particularly in the rest of the world but also in the U.S.” Wood went further, predicting an environment similar to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, but one that she is “not at all worried” about.

According to Reuters, and importantly for context, in December 2021, Wood warned that deflation, rather than inflation, would be the largest risk for financial markets and the economy in 2022.

Predicting the economy is always challenging, and predicting the market’s response to economic developments is even harder. Nevertheless, knowing what the consensus narrative is and what thought leaders consider viable alternatives is useful. Because if there is one thing that is easy to predict, it is that investors hate surprises, and a deflationary surprise could be a particularly painful one for the unprepared.

The Polen Capital Global Growth Fund own shares in Amazon, Alphabet, and Microsoft. This blog was prepared 04 December 2023 with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade these companies, you should seek financial advice.

It could be disinflation that is the issue in the first part of the year.

inflation may well rise again in the second half of next year , energy will be the major contributor , as well as services driven inflation .

it may well as mentioned bring down consumables stuff , the inflation will remain persistent for while governments cant bring there spending under control , the budget has locked a lot of that in already .

Of course Ben, you’re correct. That is indeed a possibility with a non-zero probability.