Big Australia policy fuelling inflation and a housing crisis

Post-pandemic Australia is experiencing a remarkable surge in its population. Predominantly driven by a sharp incline in net migration after border restrictions were lifted, this boom, which of course brings more customers for businesses, also puts pressure on prices, entrenches inflation when supply is unable to keep up and poses essential questions for the country’s housing sector.

Federal Labor’s budget predicts 1.5 million arrivals over the next five years. And while Labor’s 2023 Budget announced a newly formed Housing Accord to build one million new homes beginning in 2024, only 10,000 affordable homes over the same five-year period will be built on top of $10 billion 2022 Housing Australia Future Fund, which promised 30,000 social and affordable homes over 5 years.

Drilling deeper, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data reveals 2022’s unprecedented rise in population – a record for a single year. And the momentum hasn’t slowed in 2023. Indeed, this year the rate of expansion is accelerating. By March 2023, population growth – mainly attributed to net overseas migration – reached 454,400, a 103 per cent increase on the previous year. Based on 2.49 people per household, this suggests the creation of approximately 182,000 new households during what is clearly a housing and rental crisis.

Contrary to earlier Labor government forecasts, current indications suggest the annual growth might surpass 600,000. To put this in perspective, comparing these figures with the decade before 2020 shows a potential net migration increase of nearly 300,000 in 2023 alone.

By year-end, it’s anticipated that net migration will not only compensate for the pandemic-induced losses, which stood at around 440,000, but also add an extra 50,000 and while that number may stabilise in 2024 and 2025, they will likely remain significantly higher than the trends observed before the pandemic, amplifying the demand for housing.

Somewhat worryingly, international interest in Australian real estate meanwhile is at an all-time high. Rising house prices, which confounded many forecasters, and rental stress, reflect the considerable population growth experienced in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane

The problem for the housing crisis in our major capitals is perhaps made worse by news Labor will allow migrants on temporary work visas to leave their jobs in rural Australia and move to the cities to work, essentially severing the connection between migrants, the businesses that sponsor them and the regional communities in which they operate.

A simple calculation lays bare the challenge. With the population change to March 2023, there was a demand for about 226,000 new homes. Yet, only 170,000 were built, highlighting a shortage of 56,000 homes. Furthermore, projections for the next six months show a potential deficit of another 41,000 homes if construction doesn’t ramp up. While rentals and pre-existing houses can accommodate some of the demand, the underpinning message is clear: there is a proper housing crisis.

Heaping burning coals on the heads of those already suffering will be the fact that rising demand for construction workers and tradies will increase the price of renovations and new builds, entrenching inflation.

Despite the government’s ambitious plan to construct 1.2 million homes in five years, the current building rate falls short by nearly 40 per cent. Moreover, again using an average household of 2.49 people, the expected annual population growth of around 600,000 would consume all of this proposed supply if it were to be built on time, which of course it won’t.

While, accelerating the construction of suitable homes in desired locations, and streamlining or centralising planning for medium to high-density developments, is essential, the reality is legislation also needs to stamp out bad actors – those who seek to treat others poorly.

Take, for example, one couple with two young children reported by the ABC to be living in an inner-city Brisbane unit complex for seven years. They have been asked to vacate their home by their landlord who is heartlessly exploiting a loophole in Queensland’s rental legislation. Despite the family being willing to pay the requested rental increase, the landlord cannot accept it because Queensland law limits the number of rental increases imposed by landlords in any year. So, to capture the available rental income increase, the landlord is evicting the family and commencing a new lease with different tenants. The law was implemented to stabilise the housing market and address rising living costs, but some operators will always ignore the spirit of poorly drafted legislation, find a way around it or test its limits.

When the N.T. put a price on the scalp of every cane toad caught and killed, some Territorians began breeding cane toads in their bathtubs! Bad actors. Just as N.T. policies were unable to prevent the migration and spread of the cane toad crisis, the Federal Government’s current immigration and housing policies will be unable to prevent a housing crisis.

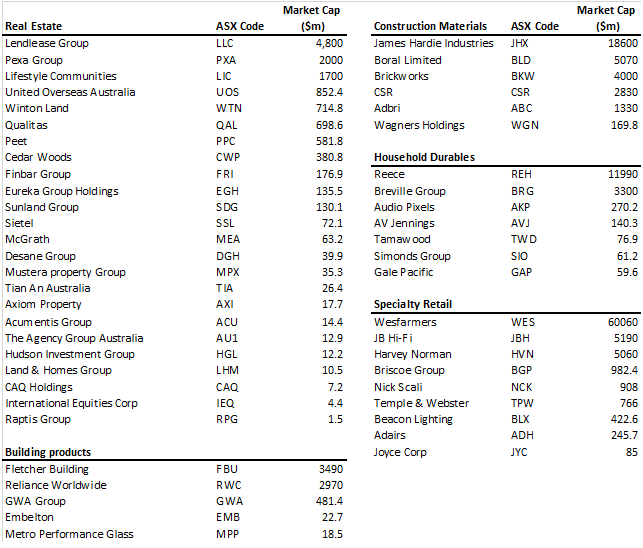

A housing supply crisis may be terrible for buyers and renters but it a represents a potential boom for various participants. Their individual exposure to the benefits will vary as will the timing of any benefit. And keep in mind the supply of labour to fulfill demand is restricted limiting the upside or perhaps delaying the benefits. With that in mind, Table 1., compiles a list of companies with exposure to the theme.

Table 1. Companies directly and indirectly exposed to Australia’s real estate supply crisis

Are you sure about the Cane Toad example? I couldn’t Google it. If it is true, it is a cracker of an example of unintended consequences of govt intervention.

Reported to me in Darwin by those who witnessed it Chris.