Rates go up; house go down

As we predicted last November, Australian house prices have now topped out and begun their march lower. A quick visit to any of Australia’s holiday hotspots will reveal a testament to the sudden end of the most recent boom – a plethora of properties advertised for sale at the vaguest possible price known; ‘Contact Agent’.

When a vendor wants more than a property is worth in the current market, and the agent cannot persuade them to be credible, rather than scaring off potential buyers with a now unrealistic asking price, the agent invites potential buyers to call.

Some of the hottest property markets in the country became decidedly cool, even before the RBA decided to lift the overnight cash rate for the first time in a decade by 25 basis points earlier this week.

We have consistently pointed out property forecasters need only to watch one measure to divine the future direction of property prices. While somewhat amorphous, that measure is ‘access to credit’.

In November last year we used this measure to announce “The boom is over (for now)” citing the changing conditions for property credit access and specifying APRA’s October increase in the minimum interest rate ‘buffer’ it requires banks to employ when assessing serviceability for new home loan applications. In October, the buffer was increased from 2.5 per cent to 3 per cent above the rate offered on the product being sold.

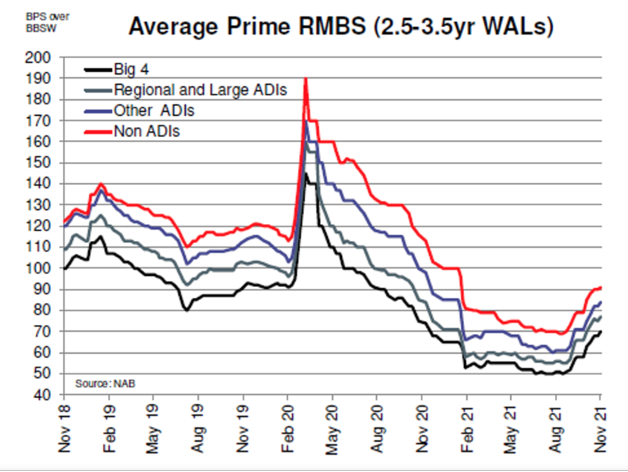

In that blog post we also published the chart shown in Figure 1. revealing, the rising cost of bank funding and concluded “It all points to a property market-cooling.”

Figure 1. Bank funding costs bounced higher from August last year

When banks or APRA, for example, and as they’ve done previously, restrict lending in any way, to any subset of buyers, such as to investors, or limit the proportion of interest-only loans, change the price of loans or even blacklist postcodes, the demand for property, and consequently its market value, will be impacted.

And while the RBA overnight cash rate change – during an election campaign, mind you – will dominate political headlines, it’s arguably not the most important rate that matters to property investors.

What matters for property investors

The rate at which banks can access money over two- to three years matters more for property investors. At the 2 November 2021 monetary policy meeting, the RBA Board discontinued its targeting of 10bp for the April 2024 Australian Government bond, exiting from the yield curve control (YCC) policy it announced on 19 March 2020 – the depths of the pandemic. As a result, two-year bond yields promptly rose (they were starting to creep up even before the decision as traders bet on the policy’s conclusion), and the cheapest domestic source of mortgage funding the banks had ever seen vanished.

Before the RBA’s decision to terminate YCC, the rate on a four-year fixed-rate mortgage for owner-occupiers offered by the NAB was 1.98 per cent. Today, that same loan is 4.79 per cent. While the rate remains low, the price is 142 per cent higher. For every million dollars borrowed, a purchaser who was once annually paying $19,800 interest, is now paying $47,900.

As an aside, Australia’s housing market sensitivity to credit access is not unique. Home sales in the US have also slowed over the past few months amid rising mortgage rates. The average rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is above 5.1 per cent, and the highest since 2010. At the same time Australia’s four-year fixed rate has surged, the US 30 year fixed-rate mortgage has jumped the fastest in four decades.

Consequently, the volume of US home sales in March, according to the US Census Bureau, has fallen 23 per cent from the January peak of 993,000 units to 763,000. Unsurprisingly, this is having serious second-order effects on consumer confidence and behaviour.

How about sales volume

Here in Sydney, sales turnover has similarly slumped, by 27 per cent year-on-year. In Melbourne sales turnover is 14 per cent lower and 15 per cent weaker in Brisbane.

The slump in sales turnover, just as vendors now race to market to avoid missing the end of the boom, has resulted in a lift in the number of listings and unsold properties, and it will ultimately lead to a rise in the numbers of days it takes to sell them. Of course, election years never help either.

As demand falls, turnover will retreat further, properties will remain on market for longer and those vendors keenest to sell will meet the market. When that happens prices will fall further. Remember, it is the marginal buyer and seller, this weekend, who determine property prices for everyone else.

Eventually, annual price growth measures will flatline and then, quite possibly (indeed likely) roll over. Last November, Sydney prices, by way of example, had grown by an annual 25.8 per cent, but as the pace of increase slows each subsequent month, and quarter, the annual change must cycle much higher historical numbers, ensuring a deterioration in annual growth rates.

Table 1. Annual increases are much tougher comparators

ABS quarterly Residential Property Price Index (unsustainable boom in red)

| Quarterly Change (%) | Annual Change | |

| Mar-2013 | 0.7 | |

| Jun-2013 | 2.5 | |

| Sep-2013 | 2.5 | |

| Dec-2013 | 4 | |

| Mar-2014 | 1.4 | 10.79% |

| Jun-2014 | 1.9 | 10.15% |

| Sep-2014 | 1.2 | 8.75% |

| Dec-2014 | 2 | 6.66% |

| Mar-2015 | 1.6 | 6.87% |

| Jun-2015 | 4.7 | 9.80% |

| Sep-2015 | 2 | 10.67% |

| Dec-2015 | 0.2 | 8.72% |

| Mar-2016 | -0.2 | 6.79% |

| Jun-2016 | 2 | 4.04% |

| Sep-2016 | 1.5 | 3.53% |

| Dec-2016 | 4.1 | 7.56% |

| Mar-2017 | 2.2 | 10.15% |

| Jun-2017 | 1.9 | 10.04% |

| Sep-2017 | -0.2 | 8.19% |

| Dec-2017 | 1 | 4.97% |

| Mar-2018 | -0.7 | 1.99% |

| Jun-2018 | -0.7 | -0.61% |

| Sep-2018 | -1.5 | -1.90% |

| Dec-2018 | -2.4 | -5.21% |

| Mar-2019 | -3 | -7.40% |

| Jun-2019 | -0.7 | -7.40% |

| Sep-2019 | 2.4 | -3.73% |

| Dec-2019 | 3.9 | 2.48% |

| Mar-2020 | 1.6 | 7.34% |

| Jun-2020 | -1.8 | 6.15% |

| Sep-2020 | 0.8 | 4.49% |

| Dec-2020 | 3 | 3.59% |

| Mar-2021 | 5.4 | 7.46% |

| Jun-2021 | 6.7 | 16.76% |

| Sep-2021 | 5 | 21.63% |

| Dec-2021 | 4.7 | 23.63% |

As Table 1. demonstrates, the more recent quarterly price increases were between three and nearly seven per cent, contributing to annual increases of over 23 per cent.

Accelerating annual house price growth drew in many property buyers and speculators, amid a fear of missing out.

As the strong quarterly numbers roll off the calculation of the annual rate however, annual house price growth will be more muted, dissuading speculators, and further dampening demand.

In March, IBISWorld predicted Australian house prices will fall by 5.2 per cent in 2022-23. Sydney prices are predicted to fall 9.2 per cent.

Perhaps more significantly, the Reserve Bank of Australia estimates property prices could fall as much as 20 per cent if cash rates are raised 200 basis points.

This flies in the face of a recent consumer survey by investment bank Barrenjoey. Keeping in mind 60 per cent of Australian mortgagors hold variable-rate loans, and are therefore most sensitive to interest rate changes, the Barrenjoey consumer survey revealed property owners are out of step with the market and the RBA.

Barrenjoey’s Consumer Health check published 28 April 2022, indicated consumers expected their mortgage rate to be, on average, 130bps higher in 12 months’ time. This is an optimistic assessment when compared to the money market, which is pricing circa 300 basis points of interest rate increases within twelve months.

And despite consumers’ anticipating interest rates will move higher, they expect house prices to remain flat over the coming two years. As mentioned above, the RBA has warned a 200bps rise in interest rates would likely lead to a 15 per cent decline in real house prices.

As an aside, this is classic RBA ‘jawboning’ by the way. Much better to quell animal spirits by planting the seed of material rate rises, than to materially raise rates. The economy would most likely contract if rates were raised as much as the RBA warns. More jawboning is likely.

It is very likely the circularity of RBA rate rises, house prices declines and consumer behaviour will keep a lid on the rate rises and make the most bearish predictions regarding rate rises wrong. As we have written about here frequently, it is not in the interests of the RBA, APRA, the banks, the government or the financial system to see a steep decline in house prices. As the RBA sees house price declines accelerating I expect they will temper their enthusiasm for rate hikes, unless of course they have no choice. That latter scenario involves current high short-term inflation expectations leeching into long-term expectations.

Back to the present, and the simple fact is access to housing credit is now tighter by virtue of the fact the ‘buffer’ went up in October and now it has become more expensive as well. When access to credit tightens, property prices decline.

Most property buyers of course plan to own for many years and selling into a declining market is usually accompanied by an upgrade in the same market. And so, property price changes for current owners are less relevant than for those yet to enter, or for those looking to add to their property portfolio. For those buyers, news of declining prices may be welcome news indeed.

As I commented in your Jan 5 article (a good year for investors) I still think you’re wrong on inflation – it’s sticky and the housing market (and the rest of us) will pay a price. You could say – well who saw Ukraine coming – but that’s the point – the world has changed.

Gary North:

The Mirage of Inflation

Thy silver is become dross, thy wine mixed with water (Isaiah 1:22).

The prophet Isaiah was publicly criticizing the nation as a whole. He also spelled out the crimes of political rulers. They were bribe-takers. They were companions of thieves (v. 23). They rendered false judgment, cheating widows and orphans (v. 24). But before these crimes, he mentioned monetary debasement: cheap metals mixed in with silver. The word “debase” comes from “base” metals — cheap metals. This was monetary inflation.

Isaiah was making a point. The sins of the nation had debased the nation. The corrupt practice of silver smelters was to mix low-cost metals into the molten silver. This produced bars that looked like pure silver, but were not. This was counterfeit metal. It was deceptive.

The society was ethically corrupt. The society was ethically counterfeit. But the purging would be real.

The debasement of Isaiah’s day was kids’ stuff compared to today. That was because of the limits of deception. Pour too much dross into the molten metal, and it will no longer look like silver.

Today, most money is digital. All digital money is counterfeit money. We do not even see the money any longer. We use pieces of plastic. Computers communicate with each other.

Counterfeit money is morally wrong. It is a form of theft. But economists do not like to invoke ethics in their analysis of economic cause and effect. They also do not like to criticize theft by civil governments as theft, for that brings up this ethical issue: “Thou shalt not steal”

Hi Roger,

I agree with everything you said.

Is the next logical conclusion “House go down, Bank go down”? The Montgomery Fund is 21% in banks as at 30 April.

Thank you so much for the education you give freely to all of us.

Phil