China Watch

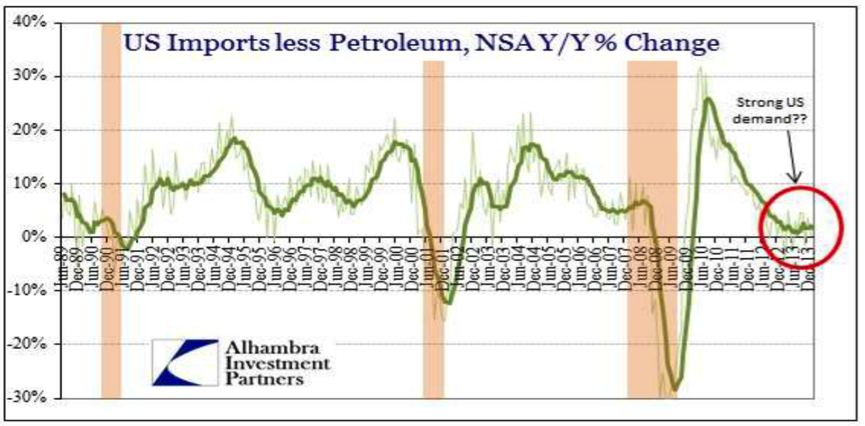

In February 2014, Robert Brusca, Chief Economist of FAO Economics, was quoted as saying: “U.S. imports are weak. And imports are closely linked to GDP. Weak imports suggest that there will be more weak GDP reports to come. That is bad news and it is the kind of bad news that trumps the good news”.

More recently, another US-based analyst provided insights that reflected this turn of events, writing: “The year-to-year change in non-petroleum imports has been sloping downward over the same period – even though the stronger trade-weighted dollar effectively raised the purchasing power of importers. Non-petroleum import growth (see Chart 1) is currently at levels more associated with recessions rather than expansions.”

Chart 1

If US import growth is down, it likely means Chinese exports must be down.

We believe growth in China is headed towards 5 per cent, if it is not already there. A year or two ago, when growth was reported at 11 per cent per annum, any talk of 5 per cent growth would have been heresy, and yet here we might just be.

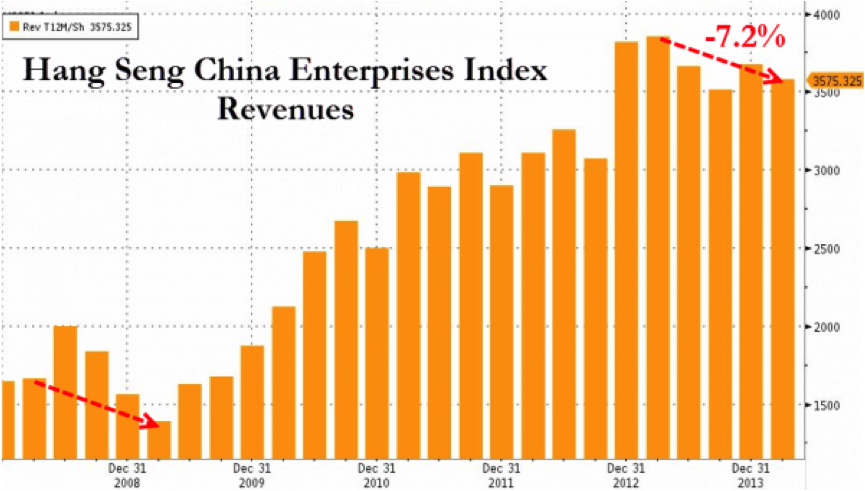

According to the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index (see Chart 2), first quarter Chinese company revenues fell by more than seven per cent compared to the previous corresponding period. The fall is significant because it makes the ability to grow earnings much more challenging and often through cost cutting – lower prices for inputs being demanded such as raw materials or labour.

Chart 2

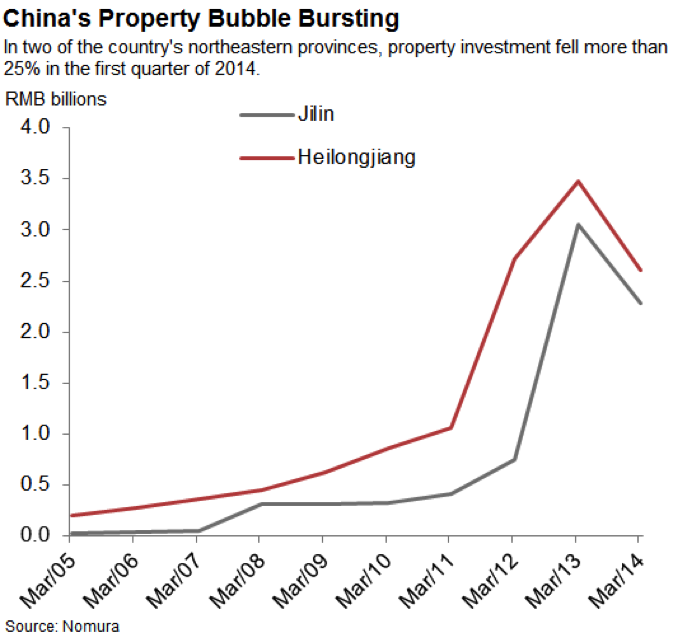

Finally, as Chart 3 demonstrates, it appears that China is waking up from its property dream. Only time will tell whether it was a pleasant one, or a nightmare.

Chart 3

According to Nomura, property investment turned negative in four of China’s 26 provinces in the first quarter of 2014, and in two of them, Heilongjiang and Jilin, the fall was greater than 25 per cent. To Nomura, that’s a warning sign of similar problems to come in other Chinese provinces.

As you are no doubt already aware, falling levels of construction and sales typically follow falling investment.

The property market has done much heavy lifting in China’s emergence as an economic powerhouse, so given the real estate industry – including steel and cement – accounts for somewhere between 16 and 25 per cent of GDP, the impact of slowing investment could be significant.

The bulls however, which include UBS economists, suggest: “Government still has the means and willingness to mitigate a property downturn”.

They might be right, but in the battle between unconventionally deep Communist Party-pockets and conventional economic forces – driven ultimately by people with behaviour that’s been repeated countless times over dozens of generations – the Communist Party will have to win.

And we repeat again, our comments from earlier this year: debt, even if used on another throw of the ‘infrastructure-spending’ dice, cannot expand forever at rates above income growth. When this expansion stops, economic growth must slow, with massive implications for iron ore and coal prices, if not Australia’s prosperity itself.

Some people suggest that Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, the President of the People’s Republic of China, and the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, would be ‘rolled’ from his position if growth floundered to 5 per cent, so there is every incentive not to print that number. But conventional economic forces appear to be conspiring against those efforts.

Postscript: Take this with a grain of salt… as we have been told, by the relative of a very senior figure in the Australian resources sector who has just returned from Sierra Leone via China – that his uncle came back from China very bearish. He reckons government is instructing all steel mills to reduce capacity back to minimum levels that will maintain employment at status quo, that stockyards are full everywhere and is suggesting iron ore could fall back to $80t.

good to have a contrarian point of view.

I worked for a US conglomerate for 26 years…22 of those in Taiwan, Hkg + China and the last 14 years (1997 to 2011) in China.

We trade & manufacture food related stuffs…animal feed & it’s ingredients, processing of poultry etc.

I managed a 3000mt soybean crush plant in Guangdong from 2006-2011.

Trust me when I say the chinese government can manage MAJOR crises.

They have the will (to maintain the status quo IE retain absolute power)…and they have the means…lots of money they can throw at any problems that come along.

The property bubble wil burst IF the chinese govt feels its okay to let it burst.

The steel mills will run or shut down depending on what the chinese govt want. Just saying “A huge mistake to expect China’s economy or govt etc to behave logically “. They are still a communist country with power & majority of wealth in hands of small % of population.

Thanks for sharing Ronald.

Just returned from a trip to Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Yiwu and the traffic at the wholesale markets was the quietest I had seen. Factories offering discounts to bring orders forward. No stop though in the rising cost of apartments in the hub of Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Mind blowing property price rises in the inner city.

Not sure about the 5% growth figure in China, anecdotally I see some retail stocks posting excellent sales numbers.

For example OSIM Ltd (code O23), a SGX listed retail company with stores in 40 Chinese cities just reported 20% sales growth across its stores, its 21st consecutive quarter of growth. Maybe they are the exception to the rule!

Hi Roger, here is an article today raising alarm bells over the Chinese property market:

Peter Cai |

52 min ago

Economy |

China

Before the burst of the Japanese real estate bubble in 1990, Tokyo’s total land value was about $US4.1 trillion, or 63.3 per cent of US GDP. When Hong Kong’s apartment prices crashed in 1997 the land value for the city was about $US5.7 trillion, or 66.3 per cent of US GDP.

Guess what? Beijing’s land value in 2012 was about $US10 trillion, or 61.6 per cent of US GDP. Do you see the scary parallel now? The vice-president of China’s largest property developer Vanke, Mao Daqing, certainly does. In a leaked speech that is still causing ripples in China he said Beijing’s land value was a very scary number indeed (What keeps China’s biggest property developer up at night 7 May 2014).

“Multiple pieces of evidence suggest that the Chinese property market in 2013 shared many characteristics with that of Japan and Hong Kong before the bursts of their asset bubbles,” Mao said last week at a closed door industry forum. “From the perspectives of the percentage of income that a household spends on housing expenditures, the rapid growth in Beijing and Shanghai is approaching Tokyo and Hong Kong levels before they went bust,”

Analysts and commentators are shifting their attention to the next weakest link in the Chinese economy — the property sector — which accounts for 16 per cent of GDP and 33 per cent of fixed asset investments. Wang Tao, the chief China economist for UBS, sees it as the biggest risk to the Chinese economy. Zhang Zhiwei of Nomura believes the sector is facing a major correction and it is no longer a question of if and when, but how much.

However, it is Mao’s penetrating analysis that offers the most worrying insight into the sector. On Wednesday, China Spectator wrote about the rapid build-up of inventory and the high level of leverage of property developers in China, according to the leaked speech.

Mao is putting China’s over-investment in the property sector into a global perspective. In a mature and stable market, an average family owns 1.1 houses and each person occupies 1.1 rooms. If we apply this standard to China, Beijing is still facing a shortage of housing but many other cities are more adequately supplied if we include existing inventories, he says.

Mao uses standard industry measurements such as ‘new units under construction per thousand people’ to illustrate the dire state of over-investment. Between 2009 and 2011, China built 1.85 billion square metres of floor space or 16.27 million residential units. It works out to be 12 new units per thousand people.

That number is about the peak construction level in many developed countries. Mao says though that this number is acceptable but has more or less reached the peak — and this does not even include other houses under construction that are not built by commercial developers.

If he was to include other housing projects apart from commercial development, China’s housing units constructed yearly per thousand was more like 35 units in 2011. This far exceeds anything we have seen even during the boom years of Japanese and Korean construction, which didn’t exceed 14 units.

“That was a peak without precedent in human history,” Mao said according to the leaked transcript of the meeting.

Like many other things, it is dangerous to overgeneralise in China. First-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen still face an under-supply of housing, and there are signs of sluggish demand recently due to a generally gloomy outlook for the sector.

Third- and fourth-tier cities, which account for 67 per cent of total construction, are roughly building at the national average rate. Mao is most concerned about second tier cities — mostly provincial capitals — which account for nearly one third of total construction in China.

Housing units under construction per thousand was 30 in 2011, more than double the international average during their peak development period. For example, the figure for Hohhot, the Inner Mongolian capital, was 70 for the last three years, while it was 49 for Shenyang, a major provincial capital city in the northeast, and 38 for Xi’an.

“In the past three years, housing construction frenzy has reached its highest peak in human history. For cities that can attract new migrants, it is safe to be building between 20 and 25 new units per thousand people,” he said.

“But some second-tier cities are building 30 or even 40 units per thousand people every year and we must pay attention to that.”

In summary, Mao believes the level of housing construction has reached its upper limit. He still sees potential in third- and fourth-tier cities in coastal provinces, where living standards are approaching industrialised countries.

However, he is pessimistic about cities with a high level of inventory and can’t see room for any price increases for at least the next few years. Even for the first-tier mega cities like Beijing and Shanghai, prices are among the most expensive in the world. They’re even more dear than Tokyo and New York, two of the most expensive cities in the world.

“We think housing prices are quite reasonable in New York,” he said. This rare insight from one of China’s most influential property sector executives should serve as an alarm bell to people who are concerned about the health of the Chinese property sector

“Before the burst of the Japanese real estate bubble in 1990, Tokyo’s total land value was about $US4.1 trillion, or 63.3 per cent of US GDP. When Hong Kong’s apartment prices crashed in 1997 the land value for the city was about $US5.7 trillion, or 66.3 per cent of US GDP.

Guess what? Beijing’s land value in 2012 was about $US10 trillion, or 61.6 per cent of US GDP. Do you see the scary parallel now? ”

Eery