Insightful Insights

-

How will the New Lease Accounting Standards impact my view of retailers?

Roger Montgomery

October 29, 2010

Joab is a regular visitor and commentator on my Insights blog and he’s a Value.able PHD graduate. Joab has put together an elegant summary of the impact – on retailers particularly – from the proposed changes to accounting standards for reporting lease liabilities to better reflect the contingent liability that is an operating lease.

No need to thank Joab. He’s delighted to help and I am delighted he went to the very great effort and time to contribute.

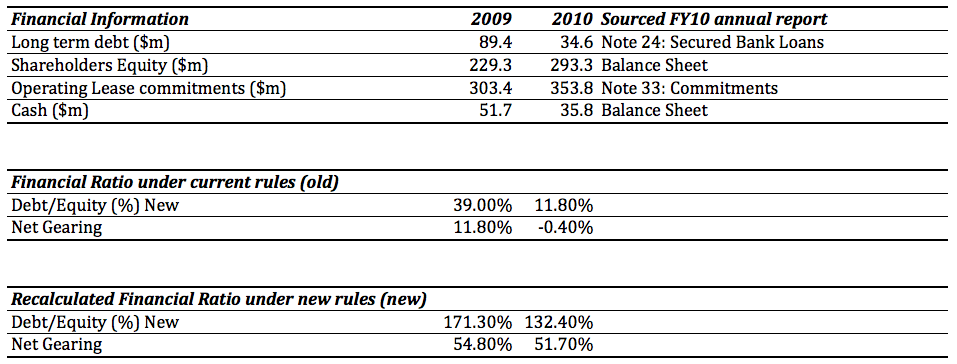

Why are the changes important? The impact of a bigger asset and a bigger liability will have no change on equity, but when you compare a bigger debt to the same equity, you will get a higher Debt to Equity figure. This will impact my Montgomery Quality Rating (MQRs) next year.

So here are Joab’s thoughts (with the community’s thanks):

Current State:

A draft proposal on accounting standard for leases was issued recently. This proposal could still be subjected to change as it is not yet finalised. That said, the principle of what it is trying to achieve is not expected to change.

Estimated timing:

Target date is to issue a finalised standard in 2011.

Key changes:

The information below focuses on the lessee’s perspective and has been simplified to highlight key impacts.

1. Operating leases will be on balance sheet as a lease liability (there will no longer be a distinction between operating and finance leases);

2. A corresponding asset will be recognised, separately on balance sheet, which offsets the operating lease liability;

3. Rent expenses will be replaced with depreciation and interest expenses;

4. Operating cash flow will no longer include cash outflow on rent. Instead, rental cash flow will be in the Financing Activities category as ‘Principal and Interest repayment’.

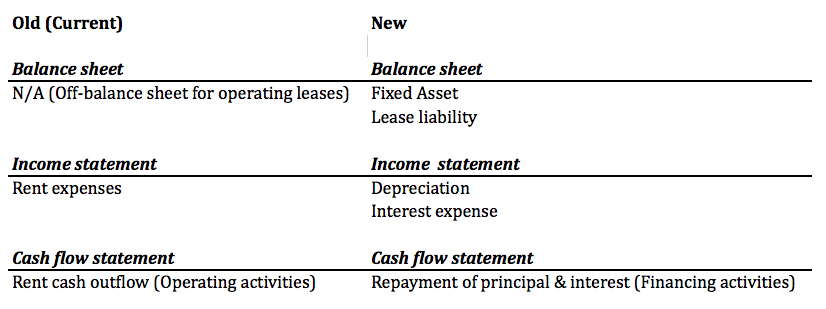

The table below compares the current and the new accounting rules on the financial statements.

Standard setters are open to feedback before end of this year.

Key Impacts:

– Financial ratios on gearing will suffer with more debt on balance sheet. For example: debt/ equity ratio, gearing ratio, interest cover ratio.

– Cash flow from operating activities will improve because rent will be presented in financing activities

– EBIT or EBITDA will improve as rent expense is replaced with depreciation and interest.

– Operating earnings will have a slightly different profile. Rentals expenses will no longer be a straight line expense.Using JB Hi-Fi as an example

Note:

– I have excluded discounting on Operating lease commitment to simplify the calculation

– Debt/ Equity = Debt / Equity

– Net Gearing = (Debt – cash) / (Debt + Equity)Posted by Roger Montgomery, on behalf of Joab, 29 October 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

Never too young to start learning?

Roger Montgomery

October 28, 2010

The ASX established the Schools Sharemarket Game to teach high school students about investing and give them the opportunity to put their learning into practice.

Ron feels high school is too late to start his newborn son’s investment journey so has taken Warren Buffett’s advice…

I remember reading that Warren Buffett started investing around the age of 11 and he always mentioned that he wished he started 11 years earlier! Therefore I thought my 4 month old son, Lior, shouldn’t waste any time and start reading Value.able!

All the best,

RonAnd from Graduates already in the field…

Matt: Value.able and a glass of Chateau St Jean 2006 Cinq Cepages

John: The best book in the world

Thank you Jesse, Michael, Young Les, Justin, Michael V, Matthew, Rad, Ron, Matt and John for sharing your Value.able adventures with our community.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 28 October 2010.

UPDATE: posted 3 November.

Hi Roger,

This is Max my nephew, he is not quite ready for your book but he is heading in the right direction.

Gavin

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights.

- 11 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Insightful Insights

-

Where will Value.able appear next?

Roger Montgomery

October 11, 2010

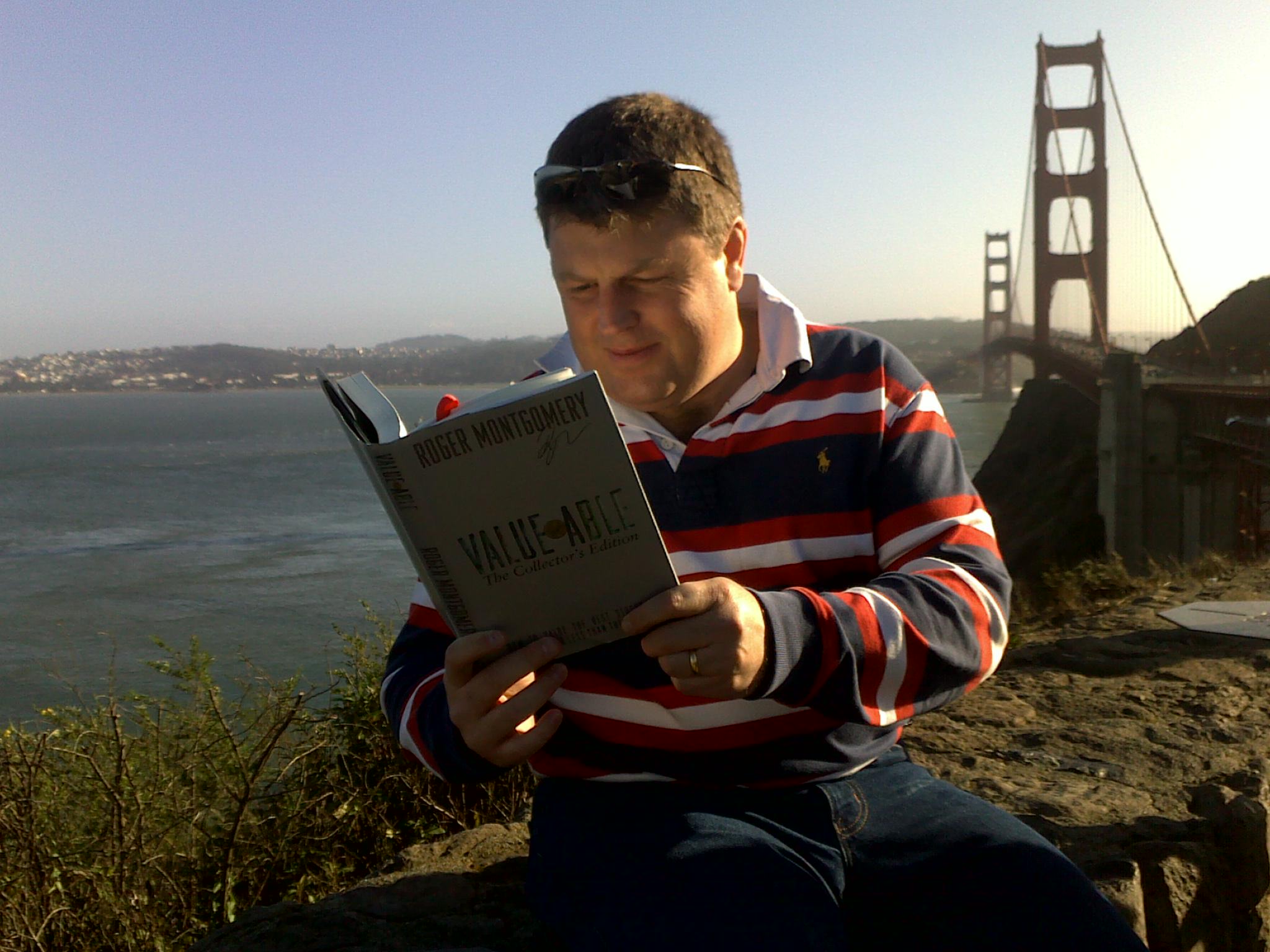

We have seen Value.able being applied on an offshore oil rig, in a deck chair on one young man’s private island and also a plunge pool in Bali. Here are two more stories from Graduates showing how they are applying Value.able in practice.

Roger,

I was recently in Galle, Sri Lanka, and was able to share some of your insights with a local spice trader, Yasiru. He was particularly interested in your comments on quality businesses and was happy to say that he maintained a competitive edge by controlling costs – he grinds and mixes the spices himself. I can report that his product is excellent and sells at bargain prices (I have no shares or other interest in his business).

Justin

And from Michael…

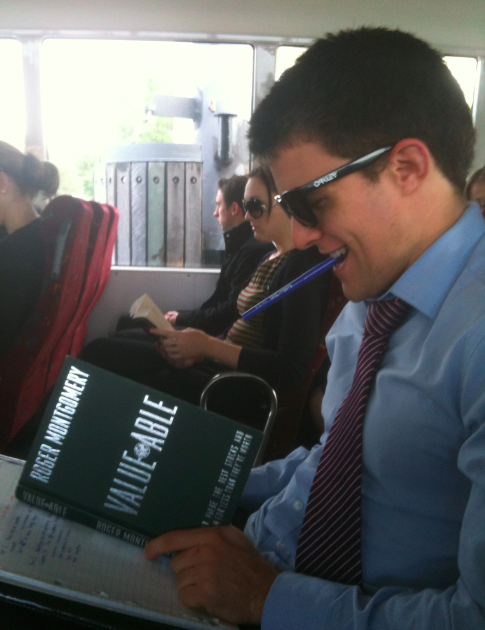

I felt compelled to shine light the legion of your followers that are not simply reading Value.able while sitting in lazy pacific island deck-chairs, exotic pools-with-a-view or even far reaching oil rigs. I give you the Montgomery Aussie Battler: An 8am-6pm, 5-day-week worker, traveling to and from work via a crammed and smelly public transport system (namely Brisbane’s CityCat). Who smiles to themselves knowing ‘the final salvation’ is possible – an early retirement thanks to Value.able, intrinsic value, margin of safety and high ROE to name a few. Thanks for starting a revolution!

Michael

P.S. Note the studious working scribbles underneath Value.able.

Please keep sharing your Value.able adventures with our community. We are enjoying the journey.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 11 October 2010.

UPDATE: 13 October 2010

Here is another pic from Matt I received today… ‘Operating Value.Able’

Hi Roger, I don’t have a tropical or relaxing environment from which to share my experience of Value.Able – I send you this picture from the Trauma theatre at 2am after an emergency operation on a car accident victim. Not a place normally associated with relaxing thoughts. However, you may not know how good an operating theatre can be for reading. After all, it has the two most important ingredients: very good lighting and plenty of fresh air (via the ultra clean ventilation systems of course). Your book has been an excellent addition to my investing education and I look forward to meeting you at one of your upcoming presentations.Cheers, Matt

P.S. the patient is doing just fine

UPDATE: 14 October 2010

I was just reading up on the “formula” when some of the guys were curious. Then, just before the game started I was trying to explain to my team mates the difference between a company’s yeild, PE and ROE. Told them to just get the book.

Cheers….Rad

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

No more Value.able Roger?

Roger Montgomery

October 7, 2010

The First Edition of Value.able has sold out.

The First Edition of Value.able has sold out.Thank you. Thank you for purchasing copies for your family and friends. And thank you for allowing me to share my way of investing with you.

If you haven’t yet purchased your copy, don’t worry. I plan to release a Second Edition paperback in November. The manuscript is with the designers and will soon be on the printing press.

You can pre-order and secure your copy at my website, www.rogermontgomery.com. Or if you haven’t yet done so, join up to my mailing list and I will let you know when then Second Edition is available.

I have received a few emails from investors who purchased their First Edition copies in early September and are patiently waiting for them to arrive. The books are delivered by Australia Post. If no one is home at the time of delivery, a parcel reminder will be left at your front door or in your letterbox and your book will be taken to your local post office. Unfortunately I have heard of occasions where no reminder note was left.

If you haven’t yet done so, please check with you local post office and if you don’t have any luck, please let me know.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 7 October 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

How do Value.able graduates calculate forecast valuations?

Roger Montgomery

October 1, 2010

I know of no other book in the world that discusses the concept of calculating future intrinsic values. You may think that is a bold statement, but its true. I have seen many books that claim to reveal Warren Buffett’s intrinsic value formula, but not one that lays out, step-by-step, what investors need to look at to determine whether intrinsic value is rising at a satisfactory rate in the future.

I know of no other book in the world that discusses the concept of calculating future intrinsic values. You may think that is a bold statement, but its true. I have seen many books that claim to reveal Warren Buffett’s intrinsic value formula, but not one that lays out, step-by-step, what investors need to look at to determine whether intrinsic value is rising at a satisfactory rate in the future.I confess to chuckling recently when one investor told me that they were finding it a little difficult to source the data they needed to calculate future intrinsic values. They also believed that my book lacked an explanation for how to calculate future intrinsic values.

So I asked whether or not they had even thought about future intrinsic values before having read Value.able? Sheepishly, the investor accepted that my book was much more valuable than they had initially concluded and subsequently told other people.

I have not found any other book in the world that has taken that little Buffett quote about finding businesses growing intrinsic value at a “satisfactory rate” and making it part of a clearly explained and defined investing process.

And for those of you who are looking for a reference to forecast equity per share in Value.able…. see Page 188, Step A.

The missing worked example for future equity. It’s easy!

How can you estimate future equity if you don’t have a forecast number such as those readily available in analyst research notes? It’s easy. Take the last known equity per share figure, add the estimated profits, subtract the estimated dividends, add any capital raised through new shares issued and subtract any equity paid back to shareholders through buybacks and you have it.

Here’s an example: In the 2010 annual report for The Reject Shop, equity at 30 June 2010 was $51.543 million (click here to see) and there were 26.034 million shares on issue. Dividing the 2010 ending equity by the shares on issue ($51.543/26.034) equals equity of $1.98 on a per share basis.

According to Commsec (click here to see), consensus analyst estimates for 2011 earnings per share and dividends per share are $1.028 and $0.744 respectively.

Starting with the 2010 equity per share of $1.98, add the earnings per share of $1.028 and subtract the dividends per share of $0.744 to arrive at an estimated ending equity for 2011 of $2.26. (If you are aware of any shares issued since the end of the financial year, you may want to take the amount raised and divide it by the number of shares issued and then add that result to the $2.26)

Now that you have seen it done, how easy is that?

A global movement begins!

I couldn’t be happier that a small group of passionate Australian value investors are even contemplating future intrinsic values! Nobody in the world is presenting you with estimates for intrinsic values, two, three or four years out and I have never seen any investor ever do it. I know of nobody else in Australia doing that, nobody has written about it before and I haven’t ever come across anyone else in the international business media discussing it either.

And now you are all doing it! It has become part of your vocabulary.

Think about that for a minute… after reading Value.able, investors are now estimating future intrinsic values, posting their estimates at my blog and Facebook page,and chatting about them online in forums and in boardrooms where previously nobody was.

If before reading Value.able you weren’t discussing future intrinsic values and now you are, then my book has had a positive impact and I am delighted. And all for just $49.95!

Consider how you are now subconsciously framing your investing decisions with future intrinsic values in mind.

Warning!

Don’t blindly combine numbers with Value.able’s valuation tables to produce intrinsic values. As I say in my book, you MUST understand the business and its prospects. I devoted an entire chapter to cash flow and its calculations. Don’t ignore it. I also devoted an entire chapter to competitive advantages. Don’t ignore that either.

Recently, Buffett sold down his holding in Moody’s because it had lost some of its competitive advantage. He isn’t selling because he has recalculated intrinsic value. It’s the competitive advantage that drives the intrinsic value.

Be careful you aren’t so focused on the intrinsic value number that you ignore all the other important factors.

Its one of the reasons I have my Montgomery Quality Ratings (MQRs). They are my own filter to help narrow the universe of companies to conduct further research on.

I put a lot of effort into writing my book and making an investment plan out of the best of what the world’s most successful investors have revealed, published and taught. And I am delighted that you have allowed me to share that with you. Thank you.

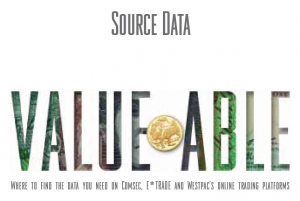

Where do I get the raw data Roger?

I have previously posted a document called ‘Source Data’, where Value.able graduates contributed their solutions to obtaining the data. Because I am receiving so many requests for help finding the data, I thought it useful to republish it. Click here or click the Value.able Source Data button to the right.

I was saddened to hear that one Value.able reader thought getting the data was all too hard and gave up. That’s like knowing there’s silver and gold a metre under your feet but saying that grabbing a shovel and digging is just too hard. If you don’t want to do the work that’s fine, but please don’t blame the guy who gave you the map, the pick and the shovel.

Using the information in my Source Data document, you should now be in a rock solid position to start estimating future intrinsic Value.able values.

Take a look at the Source Data document and you will see that the raw data is freely available. Indeed every single number you need to estimate the current intrinsic value is also available in a company’s annual report, and its all free at ASX.com.au.

With sources like Commsec and the formula I have given you for future equity, you can now freely estimate the forecast intrinsic value as well. Just go to ASX.com.au, click on the announcements link, select the company code and the year you need and voila! All the information is there in the annual report.

Value.able outlines the way I invest. I don’t have a green button that I press each day that automatically goes and buys the best opportunities. Value investing requires research and analysis. We can build devices that give us some short cuts, but they don’t replace the need to understand the business and the risks.

Why are my valuations different to Roger’s?

If everyone uses exactly the same inputs, our Value.able valuations will all be identical. Any differences therefore are due to different data. Some examples of sources of variation are:

- Online brokers’ ROE numbers are calculated differently to the way I suggest in Value.able. They use ending equity and I suggest average equity.

- Generic net profit after tax figures available on various online summary lists may or may not remove abnormal/significant or non-recurring items. Intrinsic values should be based on recurring profits, revenues and expenses. (Yes there is some subjectivity in this).

- I have noticed many of you using 10% discount rates for all companies. As I suggest in Value.able, this may be too low in some cases.

There are a variety of reasons and your Value.able valuations are different to mine.

Recently on TV I indicated that my valuation of Telstra was closer to $2.30-$2.50, but one Value.able graduate produced $3.68. I suspect that the difference is simply the choice of discount rate. Many investors will use a low discount rate because TLS such a big company with plenty of liquidity and very low risk of significant change. I however might use a higher rate because I want compensation for the fact that its future prospects are opaque and its profits haven’t grown a dollar in a decade.

Thinking about differing results, I am encouraged that many Value.able graduates were able to replicate my results exactly, or within a couple of cents.

Value.able will stand the test of time because it is based on a method of investing that works. It is a method of investing that requires time to demonstrate its value. And in time I look forward to hearing many more of your success stories.

Only a few First Edition hardback copies of Value.able remain. So if you haven’t purchased your reserved copy yet, now is not the time to ponder.

There was only one print run of the First Edition hardback. The paperback Second Edition will be available in mid November.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 1 October 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education, Value.able.

-

Part IV: Where should you focus your digging?

Roger Montgomery

September 15, 2010

While everyone else seems to have moved on from reporting season, I’m still digging my way through a mountain of analysis. I am almost done.

While everyone else seems to have moved on from reporting season, I’m still digging my way through a mountain of analysis. I am almost done.Based on the amount of comments contributed here at my blog it seems you have enjoyed reading my insights as much as I have enjoyed sharing them.

Before I get into what I have uncovered from last week’s filings, congratulations are in order. Gavin was the first Value.able Graduate to correctly pick the three companies I omitted from Part III’s second table – congratulations Gavin. Gavin picked all three despite there being thousands of companies listed on the ASX and only having six pieces of financial data. Amazing!

Congratulations are also in order to Mike and Pat, who picked all three. Great digging fellow Value.able Graduates!

The missing companies are ARB Corporation (ARP), Wotif.com (WTF) and Mineral Resources (MIN).

As always, please undertake your own research and seek and take personal professional advice before you go rush out and buy anything.

I also wanted to say a big thank you to all who have posted comments. Our Value.able investing community has benefited greatly from your contributions and insights and I am excited by the great sense of community that you have developed. I must say a special thank you to our regular contributors – the quality of your comments are amazing, and more importantly, respectful and non-judgmental. Keep them coming!

If you haven’t yet posted a comment, now is a great time to start. The Value.able community is here to share ideas and help each other. If something is on your mind, I guarantee there is someone else with a similar question. So please contribute as much as you can or ask as many questions that you may have.

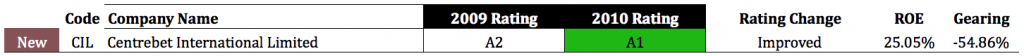

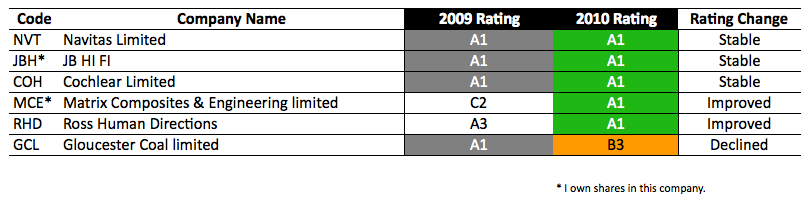

Now onto my lists – despite all my digging, there is only one new entrant into my A1 Montgomery Quality Rating this week. With three companies experiencing rating declines, on a net basis we actually lost two A1s. You can see them below.

Dominion Mining (DOM) had the largest rating decline, from an A1 to an A3. It still displays high quality metrics – with $16m in cash on the balance sheet and no debt (just watch out for those capitalised exploration expenditures), but my Montgomery Quality Rating declined. Why?

As you know, I tend to shy away from commodity businesses. It is not that they are difficult to understand, but rather difficult to forecast with a great deal of confidence – forecasting how much they will produce and when, their cost of production and/or project establishment and development costs and then ultimately, what price they will get for their production. There are simply too many variables that management can get wrong and many that are completely out of their control.

To this point I proffer Dominion (ASX: DOM), which in the most recent financial year, despite a higher average gold price, saw production slip from 98,755 ounces to 80,570 and cash production costs blow out from $438 to $697 per ounce. The combination of lower production and lower efficiencies transformed a highly profitable business into a barely profitable one in the space of 12 months. Now that’s operating leverage!

Indeed if you took all of the hitherto-labelled ‘resource evaluation and mine development expenditure’ expenses straight to the Profit and Loss account as opposed to the Balance Sheet, DOM would have made a loss of several million.

Given the many variables and accounting flexibility, if exposure to this sector is your goal, perhaps your focus could move from those who ‘look for’ and ‘produce’ to those who ‘service’ – the suppliers of the picks and shovels and those engineering businesses that install, maintain and replace all the picks and shovels. In my opinion, there are fewer variables and the economics haven’t changed since the days in 1851 when a gold rush in Ballarat saw 10,000,000 grams of gold delivered to Melbourne’s Treasury.

Back to my A1’s… the only entrant this week is Centrebet International (CIL). Remember that this is in addition to the 30 revealed so far in my previous posts – Part I, Part II and Part III. My A1’s now total 31.

CIL is in the business of online wagering and gaming and appears to have carved out a niche in Australia’s multi-billion dollar gambling market.

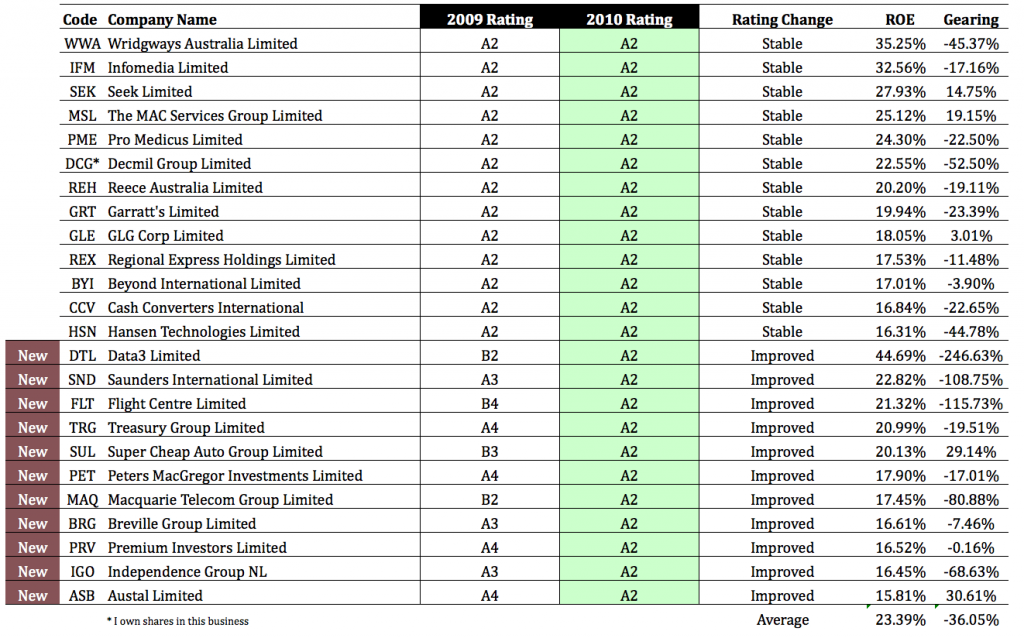

Take a look below and you will also see those companies that have achieved an A2 Montgomery Quality Rating since my previous blog post. The average ROE of this group is an impressive 23.39% (albeit around half that of my A1’s) with an average gearing level of -36.05%. There are plenty of Balance Sheets here reflecting a net cash position.

Combine my A1s and A2s (78 in total) published in the past couple of weeks and you have an excellent starting point from which to begin your own digging (by doing your own research and seeking independent personal and professional advice).

I will also mention that I may own any of the above companies and that I may buy or sell at any time – even tomorrow, and I am under no obligation to keep the list up to date in any way, shape or form. Before you do anything, YOU MUST conduct your own research and I insist you obtain independent personal and professional advice considering your needs and circumstances.

Value.able gives you the simple steps to follow to estimate a value for each company yourself and some thoughts to consider in regards to qualitative factors, such as competitive advantage. If you are not already a Value.able Graduate, why not?

Also remember that the share price may halve tomorrow. DO NOT buy shares in any company simply because I like it or own it – that is not investing, that is speculation. Speculating that I am right is not investing. That is the exact opposite of the value investing doctrine I espouse.

Reporting season will soon be a distant memory and the media, analysts and ‘investors’ will start to think about other things… the economies of the US, China and Europe will start to tickle the minds of idle analysts and commentators, but your focus should remain on great quality companies trading at very big discounts to intrinsic value.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 15 September 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

Who is in front of the reporting season avalanche?

Roger Montgomery

August 17, 2010

We are now two weeks into one of the most important times of the year for investors – reporting season. Eighty companies have reported to date, some good, some not so good – I know this because I track every single one. Yes, I am very busy. Are you wondering which companies are my A1’s now and which stocks I am interested in? In the last two weeks you will have heard me on TV saying I have bought a few things. Well, I don’t buy C5s so read on.

We are now two weeks into one of the most important times of the year for investors – reporting season. Eighty companies have reported to date, some good, some not so good – I know this because I track every single one. Yes, I am very busy. Are you wondering which companies are my A1’s now and which stocks I am interested in? In the last two weeks you will have heard me on TV saying I have bought a few things. Well, I don’t buy C5s so read on.TLS was a clear disappointment, as it has been since it listed. I have been on the front foot for a long time saying that this is a company to avoid, I hope you took notice. My valuation has fallen now from $3.00 to almost $2.50. If anyone can turn it around however I think Thodey can.

Qantas should have come as no surprise. A $300 million cash loss and I wouldn’t be surprised to see another raising of capital or debt.

Personally though I am not interested at all in TLS or QAN as investment candidates. I am only interested in the highest quality best performing businesses available – it’s here that intrinsic value can be created rather than destroyed and with reporting season just about to kick into top gear from this week, to find them, I put each company through the same rigorous process.

My initial screening process is a vital part of the investment process as it allows me to determine those companies that deserve to retain their place in the short list and it also highlights new opportunities as they arise. But to do this for some 2,000 listed Australian companies can be a very burdensome task unless you have a systematic way of analysing and comparing results in a consistent manner.

For me, it involves pulling out some 50-70 profit and loss, balance sheet and cash flow data fields from each annual report to populate my five models. All of these models employ industry specific metrics to calculate my quality and performance scores. This allows me to rank all companies from A1 – C5 to sort the wheat from the chaff.

For those not familiar with my ranking system, A1s are the simply the best businesses and the safest to own, while C5s are the poorest performers and the least safe.

Out of the 80 companies that have reported, only 5 have achieved my coveted A1 status – around 6.25% (the best of the rest).

NVT, JBH and COH had my A1 rating last year and retained it this year and there are 2 new entrants in MCE and RHD, with GCL (it was an A1 last year) having a dramatic rating decline. I tend to shy away from resource companies for obvious reasons.

On my blog I have previously spoken about NVT, JBH and COH and also mentioned ITX, so please revisit those thoughts. itX is under takeover and Navitas, it was recently reported, had been approached some time ago by Kaplan – a company I have done some consulting work for and a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Washington Post company – so a big tick for the A1 to C5 Rating system!

That only leaves MCE, an engineering business that currently generates most of its returns from the manufacture of riser buoyancy modules for deep-sea oil rigs. Its order book is already underwriting a doubling of revenue for 2011. The 2010 result revealed profits had almost tripled and significantly exceeded prospectus forecasts and it is producing returns on equity of 49% – a rate that is unavailable generally elsewhere. Borrowings amount to about $8 million compared to equity of about $60 million (of which a little over 10% is capitalised development and goodwill intangibles). Best of all, the share price over the last week is a long way below my estimate of its intrinsic value.

If you have seen me on TV or heard me on radio in the last week or so you would have heard me mention that I had bought something, MCE is it. Please be mindful that if you act rashly and go and push the share price up, you will be helping me perhaps more than yourself. Also remember that I am not recommending the stock to you and that I cannot forecast the share price direction (although I am pleased with its performance since my purchase). The share price, I warn you, could halve, for example if there is a recession and or the oil price plunges – delaying expenditure of the construction of oil rigs globally. I simply am not recommending it to you.

Also remember that I am under no obligation to keep you informed of when I buy or sell nor answer any specific questions, which means 1) you have to do your own research and 2) you have to be responsible for your own decisions. Seek and take personal professional advice BEFORE you do anything.

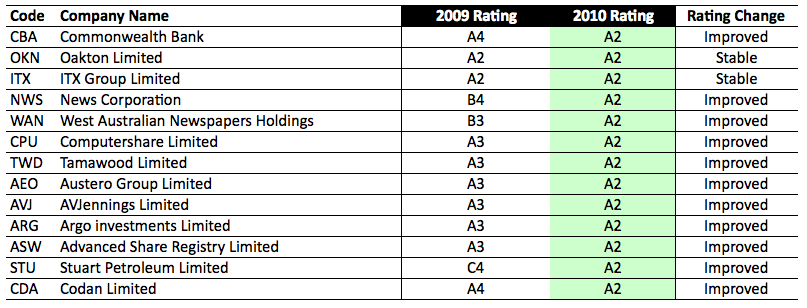

Moving on, another 13 companies have achieved my second highest rating of A2. They are listed below with their prior years rating so you can compare.

Noteworthy in this list is the excellent performance of the Commonwealth Bank (which I continue to hold in my Eureka Report Value Line portfolio, along with JBH and COH) and those companies I generally classify as being in the Information Technology sector including OKN, ITX, CPU and ASW. Both sectors appear to be doing well in aggregate.

While focus should always be placed on the A1’s (the top 5-7% of the market) at any one point in time, A2’s are still very high quality businesses. The use of the two lists in tandem will therefore provide you with an excellent starting point in isolating those who have reported high quality financials and performance levels above the average business. An important first step in the Value.able Montgomery brand of investing.

It is from here that I will select candidates worthy of further analysis (qualitative and quantitative) and possibly meet with company management, if I have not already done so. Once again I have taken you to the river I fish in, you have my fishing rods and tackle box. Now up to you to catch the right priced fish.

Please use these two lists as a starting point to conduct your own research and use Value.able as a guide to estimate your own valuations. If you don’t yet have a copy you can order one at www.rogermontgomery.com so you too can do your own valuations. Remember to always focus on the highest quality and best performing business available.

If you focus on the best when they are cheap and simply forget the rest, you should avoid more (if not all) of the disasters and should be able to build a portfolio that will give you a greater chance of out-performing the market.

Happy reporting season!

To be continued… Read Part II.

Post by Roger Montgomery, 17 August 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Companies, Insightful Insights, Investing Education.

-

The Results Revealed: How do your Value.able valuations compare?

Roger Montgomery

August 17, 2010

It has been a good ten days since I asked you the question ‘How do your Value.able valuations compare?’ And so the time has come to hand in your exam papers and reveal the results.

Some of you have pointed out that there were both 2009 and 2010 numbers in there. Yes, that is absolutely correct (but you don’t receive extra marks for pointing that out). If a company had announced 2010 results, I used the latest numbers. For this exercise I only wanted you to use the numbers to calculate the Value.able value, based on them.

The next exam is going to be a ‘finding-the-data’ test. I will nominate a company and select an annual report and you will all have to go and download it and dig up the numbers. Expect there to be some red herrings in there too. It is your money you are dealing with so it is reasonable to make sure you are being conservative.

Here are my answers to the samples I listed last week. I hope you had a chance to practice. There will be another set of examples soon so you can have another go.

The recent CFA exam saw only 39% of participants pass, so don’t be too hard on yourself if you are out on your first attempt. As Sir Francis Bacon, the 1st Viscount of St. Alban said: Truth will sooner come out of error than from confusion.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 17 August 2010.

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights.

- 74 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Insightful Insights

-

What do you think of the QAN, JBH and ITX results Roger?

Roger Montgomery

August 12, 2010

Here we are in the midst of reporting season and there are some reasonably predictable results. Qantas reported a profit today that was less than a quarter of its profit more than ten years ago. The airline reported a $112 million profit but that was boosted by $1 billion of revenue from its Frequent Flyer program and a $300 reduction in employment costs. For those of you interested in the real numbers, the company actually lost $302 million (see my chapter in Value.able on cash flow) and this can be explained by the very wide gap between the depreciation item in the profit and loss statement and the real expenditure on property plant & equipment. Depreciation looks backwards, but new planes cost more.

Here we are in the midst of reporting season and there are some reasonably predictable results. Qantas reported a profit today that was less than a quarter of its profit more than ten years ago. The airline reported a $112 million profit but that was boosted by $1 billion of revenue from its Frequent Flyer program and a $300 reduction in employment costs. For those of you interested in the real numbers, the company actually lost $302 million (see my chapter in Value.able on cash flow) and this can be explained by the very wide gap between the depreciation item in the profit and loss statement and the real expenditure on property plant & equipment. Depreciation looks backwards, but new planes cost more.Separately, JB Hi-Fi’s result was excellent but my concern is that its $94 million of cash flow (of which $67 million was allocated to dividends and $20 million allocated to paying down debt) is superfluous to its needs. Take a look at the biggest asset on the balance sheet – Inventory of $334 million. Then take a look at the creditors item in the current liabilities section. Almost the same amount!

Think about it this way; the suppliers are funding the inventory so the company doesn’t even need cash to pay have the stuff it sells and that are on its shelves. Actually it really does, the gap is about what is left over once we subtract the debt repayment and dividends from the cash flow. It is small though. Once the debt is gone and the cash keeps growing it may do something that could harm intrinsic value.

Now don’t get me wrong; JB Hi-Fi is an amazing business that retained its A1 status in this result and the risk associated with its plans to roll out more stores is very low. I also think intrinsic value will continue to rise at a satisfactory rate. The concern for me with all this cash (and there is no evidence of it yet) is that the company increases the dividend payout ratio again. This would mean a reduction in the rate of growth of intrinsic value. It could stop being the “compounding machine” it has been to date. Return on equity also appears to be flattening, which could mean within the next few years, the valuation may plateau (but at a higher level than the current price).

On an unrelated issue, I note that back on 4 May 2010, I put together a list of the companies that I though represented the last of value in a blog post entitled Do these three companies represent the last of good value? ITX was one of the companies listed and I note the company has announced “itX confirms that it is in discussions with an interested party regarding a preliminary non-binding indication of interest to acquire 100% of the ordinary shares in itX.”

I’m pleased to strike another one up for the quality rating and valuation approach advocated here at my Insights blog!

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 12 August 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Airlines, Companies, Insightful Insights.

- 29 Comments

- save this article

- POSTED IN Airlines, Companies, Insightful Insights

-

Where to find the Source Data for Value.able valuations

Roger Montgomery

August 10, 2010

Discover the fundamental data you need to create your own Value.able valuations.

Click here to download Roger’s step-by-step guide to finding the Source Data.

Posted by Roger Montgomery, 10 August 2010

by Roger Montgomery Posted in Insightful Insights, Value.able.

- save this article

- POSTED IN Insightful Insights, Value.able