Australia leads the world in the annual pace of disposable income decline

In its fight against persistent inflation, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has just introduced its 13th rate hike in this cycle at the same the financial strain on Australian households intensifies. According to a disturbing report published in The Australian Financial Review (AFR) this week, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has discovered Australia leads the world in the annual pace of disposable income declines globally.

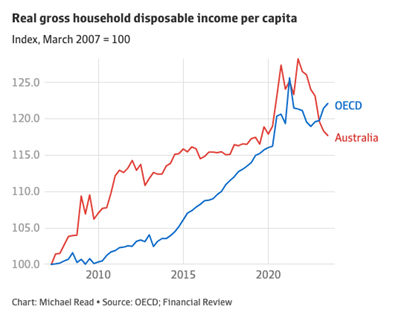

The last year has seen a dramatic decline in Australian living standards, outpacing all other developed nations, driven by soaring inflation and increasing mortgage repayments. Disposable income, when adjusted for inflation and population growth, is at a three-year low, continuing a downtrend for the seventh quarter, as per OECD data.

Figure 1. Be afraid. Be very afraid.

The economic situation poses a significant challenge for the Albanese government, with cost of living concerns topping voter issues. The AFR’s analysis shows a 5.1 per cent drop in household income within a year, marking the steepest decline among OECD countries. In comparison, the collective OECD experienced a 2.6 per cent rise in living standards. Over the same period, real household gross disposable income per capital rose 3.5 per cent in the U.S., 2.2 per cent in the UK and 6.0 per cent in Spain.

Australia’s real household incomes have seen only an 18 per cent increase since 2007, lagging behind the OECD’s 22 per cent average. Although Australia’s inflation rate is below the OECD average, wage growth fails to keep pace with that of other developed economies, affecting living standards.

A combination of surging population growth (the impact of which we have written about here) and high inflation is the crux of Australian households’ struggles. Unlike in the U.S., where many households refinanced 30-year fixed-rate mortgages at ultra-low rates during the pandemic, our variable rates in Australia have an immediate impact on disposable incomes and therefore living standards.

The RBA’s data highlights that Australia has one of the highest proportions of mortgages with variable rates, leading to significant payment increases. For example, a $500,000 loan now costs $1,210 more per month than in May 2022, a 59 per cent jump in 18 months.

The initial phase of the pandemic saw a boost in disposable incomes due to substantial government stimulus. However, this created an excess savings buffer that is now nearly exhausted, as observed by U.S. Federal Reserve economists.

Adding to the fiscal pressure is the non-indexation of tax brackets to inflation in Australia, causing more of an individual’s income to be taxed at higher rates, a phenomenon known as bracket creep. Consequently, income taxes have devoured a record portion of household incomes.

While I have hitherto been sanguine about the risk of recession and stated in November last year that Australia would side-step a recession in 2023, the case for one must be gaining strength as any lagged impacts from rate rises converge with declining savings buffers, and now, evidence of substantial drops in disposable incomes.