Aus Banks – Not all Mortgage Exposures are Created Equal

There has been a lot of discussion of late about the current state of the residential property market and the potential for a correction, or even a collapse, in residential property prices.

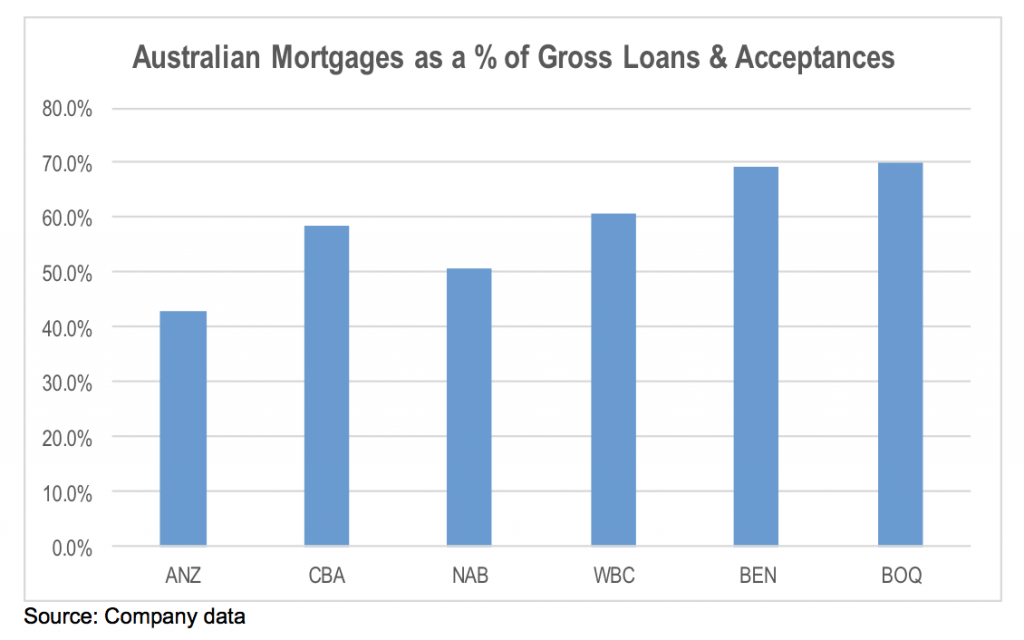

In terms of the most exposed banks to any correction in Australian residential property prices, most of the discussion revolves around the proportion mortgages make up of each bank’s loan book. As such, the most common assessment is that of the majors, CBA and WBC have the most exposure.

The chart above indicates that the regional banks have the most significant exposure to Australian mortgages, followed by WBC and CBA.

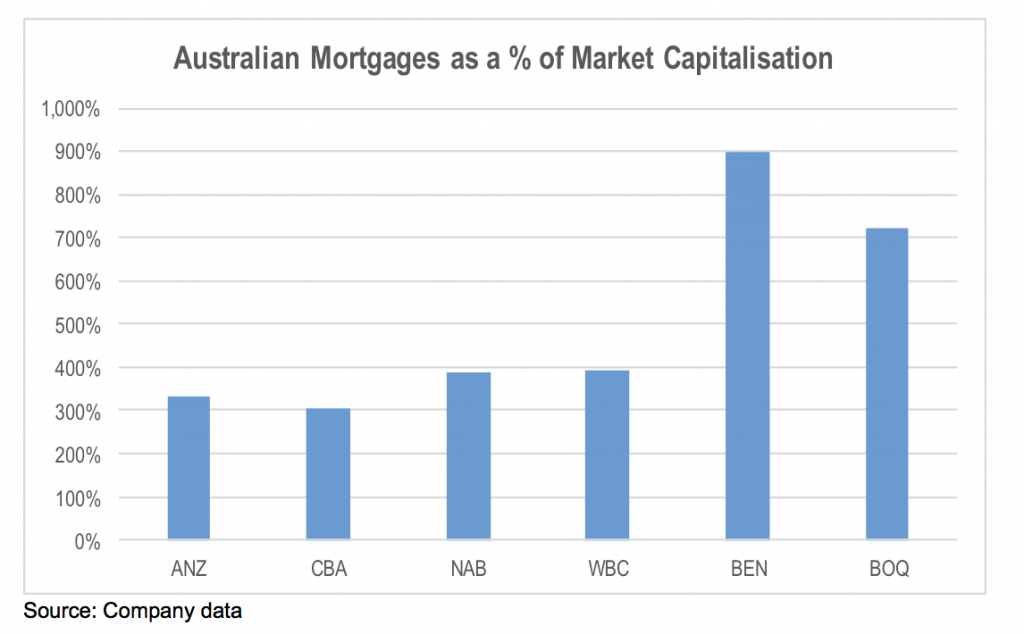

However, not all mortgage books are equal. Given that a non-performing loan is essentially a straight write off to the equity value of a bank, another way to look at a bank stock’s exposure to a downturn in Australian residential property prices is the mortgage book as a percentage of the bank’s market capitalisation. This would provide a better indication of the downside risk to the share price from an unexpected write off of a given percentage of the mortgage book. This shows a slightly different indication of exposure.

This shows an even greater risk in the regional banks. However, it also suggests a more even investment risk across the majors, with WBC remaining the most exposed, but CBA falling to be the least exposed.

Of course the above chart is a function of the bank’s price to book ratio. This is driven by the market’s perception of the bank’s sustainable ROE generation. A significant correction in the Australian housing market is likely to negatively impact sustainable ROE expectations, resulting in lower price to book ratios, particularly for WBC and CBA. Therefore, the impact on share prices would not merely reflect the mortgage impairment surprise in isolation.

Additionally, these figures do not take into account any mortgage insurance protection.

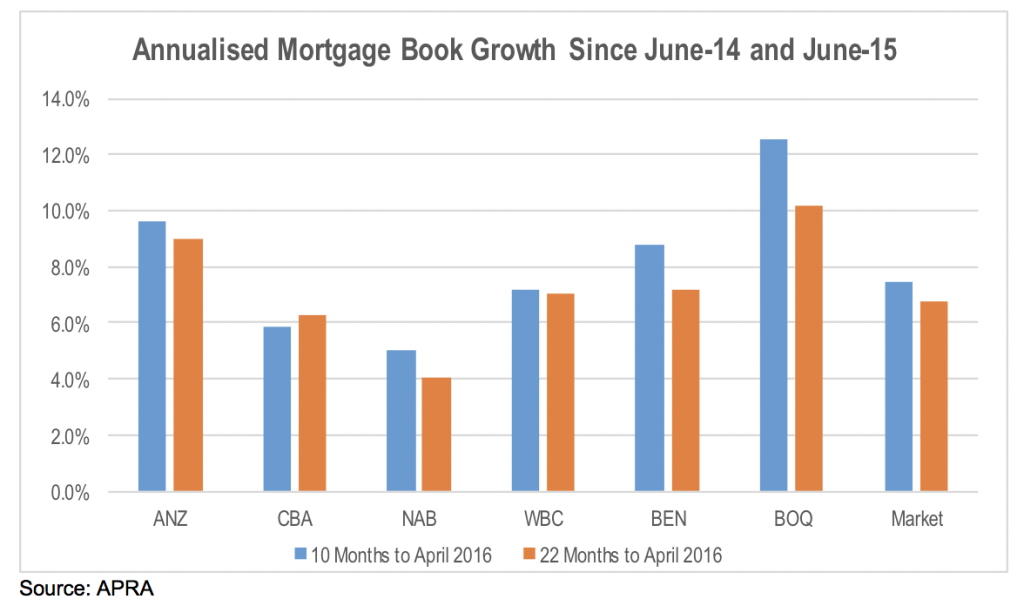

The other thing to take into account is the age of the mortgage book. Because mortgages amortise over the like of the asset, the loan to value ratio (LVR) of a mortgage falls over time (assuming the value of the property doesn’t fall). Additionally, older mortgages will have been written when property prices were significantly lower than current levels, providing additional LVR protection.

This means that banks that have been aggressively growing their loan book more recently are likely to have less equity protection against a correction in residential property prices.

If we look at mortgage book growth rates over the last 1 and 2 years, BOQ and ANZ have grown their respective mortgage books at rates well above that of the overall, while NAB and CBA have been the laggards.

What this says is that if the Australian residential property market falls 10 per cent, around 5 per cent of the mortgage portfolios of ANZ and CBA would have negative equity (ie the property is worth less than the mortgage balance), as opposed to just over 2 per cent for NAB and less than 2 per cent for WBC.

Of course, these dynamic LVR calculations are done internally and are therefore not necessarily 100 per cent comparable. But they broadly show the impact of ANZ’s more recent mortgage share growth on its exposure to high LVR mortgages.

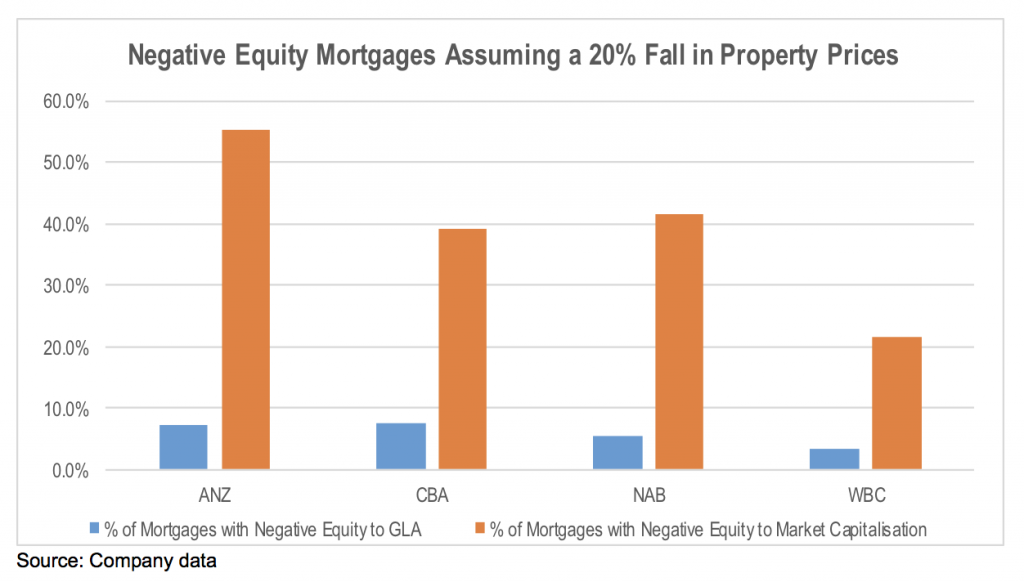

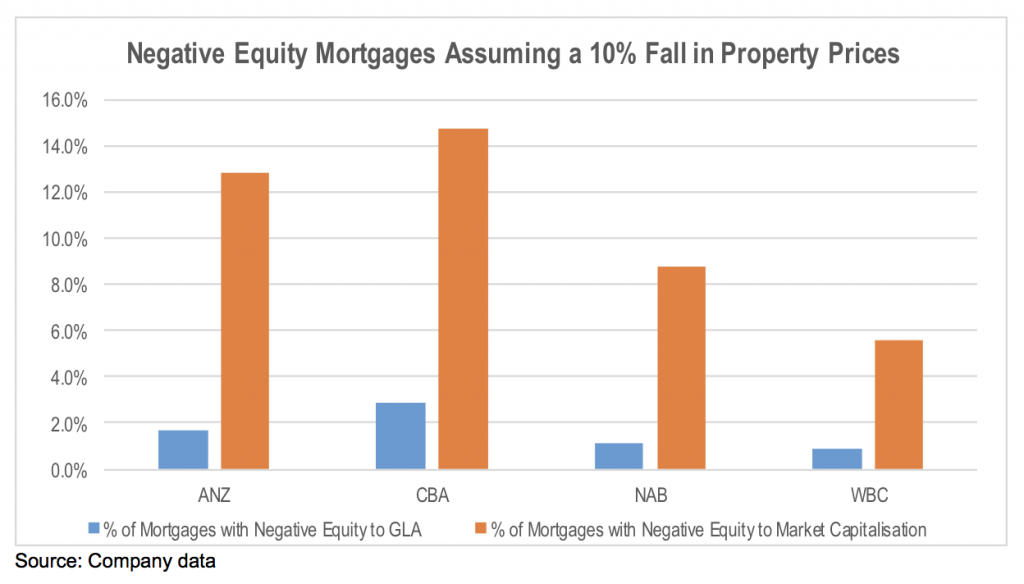

We can use these figures to determine the percentage of each bank’s total gross loans and acceptances that would be secured against residential properties with negative equity assuming a given uniform fall in Australian property prices as shown in the charts below.

Under a scenario where prices fall 10 per cent across the market, CBA shows the most risk closely followed by ANZ. If we assume a 20 per cent fall, ANZ becomes the most exposed. Of course, just because a property’s value falls below the value of the mortgage doesn’t mean the loan will go bad. However, it does increase the risk of write offs, particularly if the property downturn is accompanied by a more general downturn in economic conditions resulting in rising unemployment.

Of course, just because a property’s value falls below the value of the mortgage doesn’t mean the loan will go bad. However, it does increase the risk of write offs, particularly if the property downturn is accompanied by a more general downturn in economic conditions resulting in rising unemployment.

WBC’s risk increases significantly if residential property prices fall more dramatically due to its decision to self-insure a portion of its mortgage insurance requirements.

There are other differences that impact the quality of a bank’s mortgage book, and its exposure to any future downturn in property prices. But that is a discussion for another day.

Stuart Jackson is a Senior Analyst with Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

How can I short the bank share…

Speak to your adviser. There are options, there are inverse index ETFs, there are a variety of possibilities. Keep in mind the banks have a very heavy weighting in the index, so you may ask your adviser to consider index-related derivatives as well.

Might be time to start looking at shorting the Mortgage Insurers!

Hi Stuart,

At end of Apr you guys had CBA and WBC as your top two holdings.

Have you exited Aus. banks completely now?

Hi Gav,

We continue to hold CBA and WBC.

Hi Stuart,

Thanks for a thought-provoking analysis. I should declare that I hold BOQ, as well as ANZ and NAB. Hence my interest!

Do I read your comments correctly, regarding loans falling into a negative equity situation if property values drop by 10%?

Doesn’t that statement imply that the mortgage loans are all for an amount equal to 90% (or more) of the property valuation? Does that figure represent a large percentage of the mortgages provided by the banks?

If a mortgage is for any less than 90% of valuation, then I do not see how a 10% drop in value can lead to a negative equity situation.

Hi Alan,

The loan to valuation ratio (LVR) measures the outstanding balance of the mortgage as a percentage of the value of the property. The dynamic LVR updates both of these figures over time. So the dynamic LVR adjusts the LVR on the mortgage to reflect the extent to which the mortgage has been repaid, as well as any change in the value of the property since the mortgage was taken out. The fourth chart in the post shows that around 5% of the mortgage books of CBA and ANZ are currently at a dynamic LVR of above 90%. This means that if the value of the properties were to fall by 10%, the dynamic LVR on 5% of their current mortgage portfolio would increase to above 100%, meaning that the outstanding principal of the mortgage (ie the amount owed to the bank by the property owner) is greater than the value of the property. Hence the owner has negative equity in the property. The other 95% of the mortgage book would still have positive equity for the property owner. The next chart then looks at the book value of each bank’s mortgages at would have negative equity (ie the 5% of the overall mortgage book for ANZ and CBA) as a percentage of the bank’s total loan book and its market capitalisation. I hope that helps.

Hi Stuart,

First of all excellent charts and analysis – fantastic impromptu breakdown on the connection between commercial lending, construction, employment, and Resi-property.

On the point about about MQGs exposure, CBAs Aussie Home Loans receives wholesale funding from Mac-Bank. To what extent are wholesale markets impacted given defaults and who are the impacted players there?

Hi Dylan,

I’m quite sure what you are asking, but if you are referring the Aussie Home Loans branded mortgage products, then to the extent that this product is a white labelled offering from Macquarie then it has exposure to any increases in defaults. However, we believe that Aussie replaced Macquarie as its white label product provider in 2008. Therefore its exposure would be limited to the remaining balances of mortgages written prior to 2008, which would be very small. Additionally, these balances should be included in monthly mortgage book size data for Macquarie published by APRA. One thing to also factor in its that the increase in bank liquidity requirements has seen their ownership of RMBS increase. Therefore there could be additional exposure to mortgage default in liquid assets. Broader wholesale funding of banks comes from a wide range of sources globally.

Hi Stuart, great to see someone talking about the negative feedback loop that would be likely to occur if the building industry slowed down. With 8% of all full time employment being in the construction industry as opposed to 2% in mining it’s a real concern to me that we would only need a slow down in costruction (from record highs) to create the same effect economically as a loss of every mining job in Australia. It seems we are caught between a rock and a hard place if we keep building at the current rate the oversupply will increase in turn forcing house prices down. If we slow the overbuilding (and with most tradesman being specialised subcontractors without employment contracts, redundancy packages ect, the effect of lost jobs on overall spending would be instant) unemployment would have to rise. Is there any scenario I’ve overlooked? I hope so

It’s hard to see what that might taker over as the economic growth driver at this stage. Education and tourism are benefiting from the lower AUD, but these aren’t big enough to fully offset a fall in construction activity. If the construction sectors slows resulting in weaker economic growth, the AUD is likely to slide further. The lower AUD could also benefit other export and import competing industries, but investment in capacity might take time to come through given how significantly many of these industries were impacted when the AUD appreciated through the last decade. Relatively high corporate tax rates are also a bit of disincentive for retention of capital for reinvestment. However, freeing up economic capacity can lead to innovative redeployment of the capital. But we need the flexibility in the system to enable this to occur.

So why is a 10% property correction such a big deal? Unlike Americans in the GFC who were inappropriately given housing loans they didn’t have the income to pay for, Aussies have a very low mortgage default rate. It would need a big rise in unemployment before that would change.

I don’t care if my house falls in value next year. I’m still going to pay the CBA every fortnight for about another 10 years. Sounds like a good deal for the CBA does it not

Hi Carlos,

The 10% and 20% figures were not used as an expectation of the outlook for property prices, but to show the impact on the risk to the loan book values of the banks under certain scenarios. To your point about the connection between default and property prices, as the note states, negative equity doesn’t automatically mean the loan goes bad. Default is caused by an inability to meet payments. In Australia, this usually a result of high unemployment. The fact that default rates are currently low is really unimportant. It’s the outlook that more important. Australian economic growth has transitioned from being driven by investment in mining capacity growth, to construction over the last few years. This has been particularly important for economic conditions in Melbourne, Sydney and SE QLD. Additionally, the economic benefit from growth in construction is more broadly felt than from mining due to it being far more labour intensive. The boom in construction has been fueled by more affordable, and importantly, greater availability of credit. This has supported construction through commercial lending growth a few years back, and more recently, mortgage credit growth to complete final product sales. The big question is whether the investment will continue to grow to support overall economic growth. If prices start falling, lenders will become more reticent in providing commercial loans to developers. We are already seeing the banks pull but on commercial lending, with increased pre sales requirements, constraints on approvals in certain postcodes and reduced LVRs. This means that developers would be required to find alternative funding or kick in more equity themselves. For the time being, mezzanine financing appears to be filling the gap. This appears to be sourcing funds directly from individuals rather than traditional financial institutions. We will see how long this continues.

With a large number of residential projects due to be completed over the next couple of years, new projects of equivalent size will need to commence just to hold economic activity flat. If property prices are less certain and/or funding is harder to obtain, these projects are less likely to be replaced. The question will then become, what will take over the running to drive Australia’s economic growth? Public infrastructure spend is likely to increase in NSW and VIC over the next few years, but it will be difficult for the taxpayer to fully replace any reduction in construction spending in the private sector. The risk is that if the residential property market rolls over, the outlook for economic growth and unemployment deteriorates with it.

It would be interesting to see Macquarie on those charts, i believe they have been aggressively adding to their loan book over the last few years.

Hi Dan,

MQG has grown its mortgage portfolio at an annualised rate of 37% a year since June 2014 and 12% since June 2015 according to APRA’s data. This is multiples of the ~7% a year growth in the overall mortgage market. Unfortunately MQG provided very little data on the make up of its Australian mortgage book in its recent FY16 result, except to say that most of its Australian loans are fully mortgage insured. While MQG aggressively expanded its share of the mortgage market in recent years when residential prices were high, it must be remembered that the mortgage business is a relatively small part of the overall company. However, I wouldn’t call it insignificant.