Budget deficits, debt ratios, and bond markets: What lies ahead for U.S. investors?

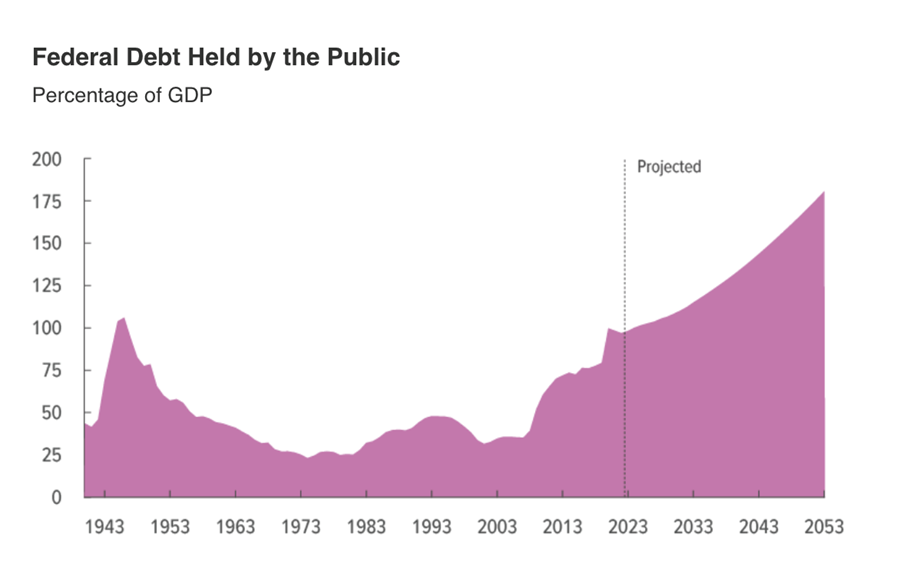

The recent removal of the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Kevin McCarthy, seems to coincide with the outlook of an unsustainable budget deficit and the likelihood the U.S. Federal Debt to GDP ratio will soon exceed the record reached in 1946, immediately after the second World War.

With the House passing the bill to keep the Government “open” for 45 days only, it will be interesting to see what the hard-line Republicans have in mind as the mid-November date approaches. And twelve months out from the U.S. presidential election on 5 November 2024, will these political shenanigans give Donald Trump even more oxygen?

Slower GDP per capita growth with the decelerating labour force growth from the aging U.S. population, combined with the increased proportional spend on healthcare, social security, and net interest on significantly higher indebtedness, will likely lead to the U.S. budget deficit to GDP ratio trend up from the current 6 per cent.

As the Government debt to GDP ratio is projected to grow significantly over the long-term, many forecasters believe the U.S. budget deficit to GDP ratio will climb towards the high single digits over the next couple of decades. Chicken or the egg? Higher budget deficits equal higher government debt to GDP ratios.

The question for investors is whether we should demand a higher risk premium on US ten- year treasury bonds, relative to inflationary expectations?

To illustrate, I have produced a chart comparing the U.S. Consumer Price Index (as a proxy for inflation) with the U.S. ten-year treasury bonds going back to 1980. Breaking this chart into two, the period 1980-2001 saw an average premium exceeding 4.35 per cent (average 10-year treasury bonds of 8.25 per cent versus an average CPI reading of 3.90 per cent). The period 2002-2023 saw an average premium of 0.5 per cent (average ten-year treasury bonds of 3.03 per cent versus an average CPI reading of 2.53 per cent).

U.S CPI versus ten-year Treasury Bonds

Since mid-2020, U.S. ten-year treasury bonds have jumped from 0.5 per cent to the current 4.8 per cent, with rising inflationary expectations. Calendar 2023 will likely be the third consecutive year when they have delivered investors a negative return – something that hasn’t happened in the past century.

It seems U.S. inflationary expectations is likely to exceed the Federal Reserve’s two percent target in the foreseeable future. Combine this with the relatively large and increasing budget deficit to GDP ratio and Government debt to GDP ratio, and it seems the risk premium on U.S. treasury bonds, relative to inflationary expectations should increase from here.