Portfolio Puzzle – The Solution

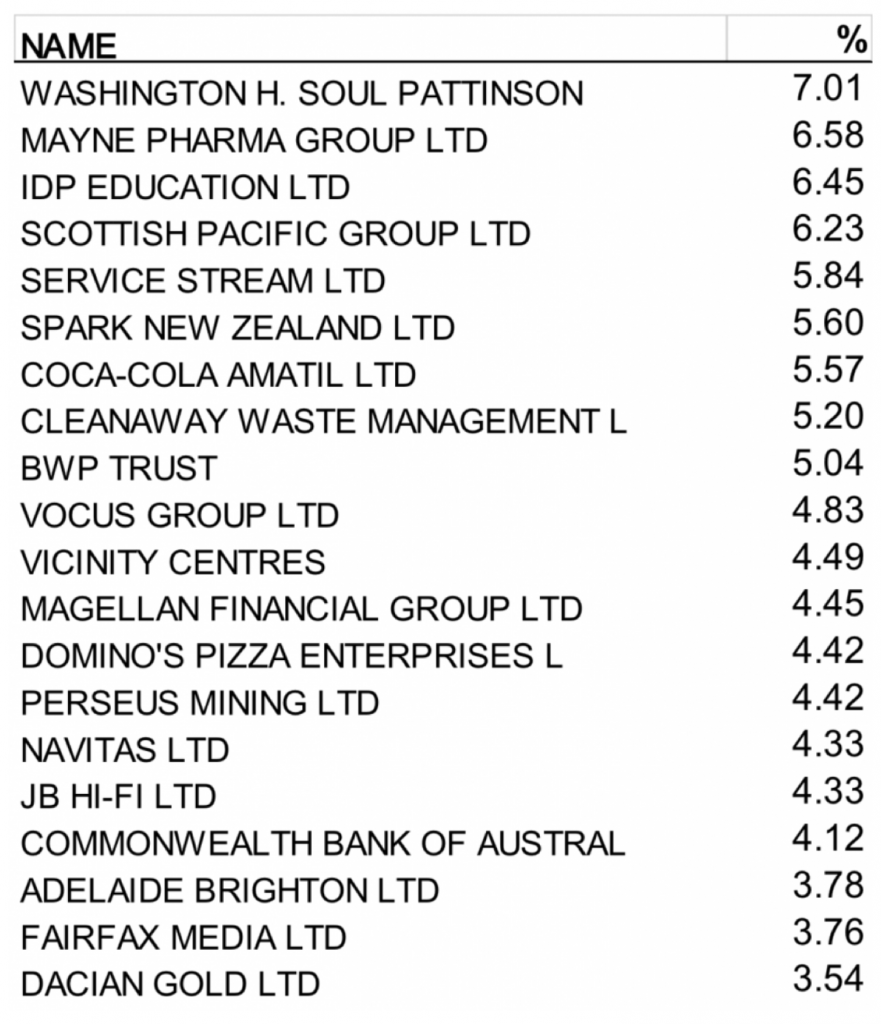

In a recent post, we set out the following 20-stock portfolio, and invited readers to think about the investment style and process behind the portfolio. To recap, the individual holdings and weights were as follows.

We also noted that the performance of the portfolio for the year-to-date has been impressive. At last count, it had delivered a solid 10+ per cent total return while the market had delivered a small negative total return, as shown here.

The question attracted a lot of social media commentary and some thoughtful assessments of the way in which the stocks might have been had been selected: including ROE, GARP, out of favour, strong market positions, etc. It’s time for us to explain exactly what it is.

Before we do that, I should note that it’s not especially unusual to encounter an investment manager who can point to strong 12-month numbers comparable to these ones. If you follow financial and investment media, you’ll encounter them in blog posts, media articles, marketing presentations, monthly performance reports and a host of other places.

There are many different ways to outperform the market, and these high-performing managers typically will represent a variety of different investing styles, but there’s one common factor that binds almost all of them, and it’s the same factor that forms the foundation for the portfolio we presented.

The factor is luck.

We created our hypothetical portfolio by randomly selecting 20 stocks from the index and assigning them equal weights at the start of the year. We repeated this ten times, and then chose the portfolio that had performed the best – the “top decile” portfolio.

This sounds sneaky, and it is, but there’s an important principle behind the sneakiness.

The proportion of investors who can realistically expect to achieve outperformance averaging +10 per cent p.a. is vanishingly small. I would expect that it would be well below 1 per cent. However, the number of investors who can achieve these kinds of results in any given year through luck is far higher – something in the order of 10 per cent, or more than ten times as many (as illustrated by our selection process).

Investors who achieve stellar short-term results will typically be the ones making the most noise at any given time. They will be among the most active in advertising, making presentations, raising capital in LICs, and appearing in fund manager profile articles in the press. They call you up and tell you all about it. The ones who haven’t done as well – not so much.

The point is this: when you encounter an investor spruiking a strong 12-month track record (or sometimes even less), it’s very likely that good luck – rather than skill – is what brought them before you. The investors that were lucky stand up and make noise, the ones that weren’t lucky stay silent.

This is the same process that produced the portfolio we set out earlier.

The take away from this is that it’s good to be alert to the underlying “process” that generates strong short-term performance numbers, especially where the longer-term numbers are weak, or don’t exist.

At the end of the day it’s far better to understand and believe in a manager’s philosophy and methods than to extrapolate from a limited run of recent success.

Thanks Tim

That brings home the concept of reviewing performance over time.

How long a time frame or rope would you give to the Montgomery Alpha Plus fund to achieve the target returns as intended.

A good question, Karan, and one I could write an essay on. To try to keep it brief, the longer the timeframe for analysis the more likely you are to get a “true” indication of strategy performance. A lot of managers suggest a 5 year investment horizon, and for a strategy with a genuine ability to beat its benchmark, this should be long enough to give you a good chance of doing so. However, it does not guarantee it – it just gives you a good chance.

For more concentrated or idiosyncratic strategies in particular, the chance of 5-year underperformance is higher, and many of our domestic funds fit this description. For example, they hold 20-40 stocks and eschew resources, and if you have a 5 year bull run in resources it may be hard for these funds to outperform. On the other hand, if you have a resources bear market, they could outperform dramatically. The nature of these funds can make them a bit ‘feast or famine’, but over very long time frames they should still do well.

In the case of the Alpha Fund, at the start of October we restructured to be much more diversified and much less idiosyncratic to substantially reduce this ‘feast or famine’ character. Following the restructure it now holds >100 positions in both its long and short portoflios, invests in a range of global markets, and avoids systemic bias against particular sectors. Under the new structure I would think it has a significantly better-than-average chance of achieving good results over a 5 year timeframe.