Why it might be time to be greedy once more

Currently, price-to-earnings ratios are at levels unseen since the 2020 COVID sell-off and the Global Financial Crisis. Many quality companies are now ‘on sale’. This is creating an ideal environment for judicious investors to take advantage of mis-priced businesses.

During bull markets, investors can only see the positives. Consequently, they are upbeat, fueling rising share prices, which in turn reinforces their bullish predisposition.

The reverse occurs in bear markets. So, my simple assessment of today’s market environment is investors are inevitably worried about the next thing that could make an ugly picture worse.

It’s entirely understandable. But it could prevent investors from taking advantage of low prices they may not see again. I should say, at the outset, I don’t know whether the market will fall further. And I am even less certain about the short-term direction of individual issues.

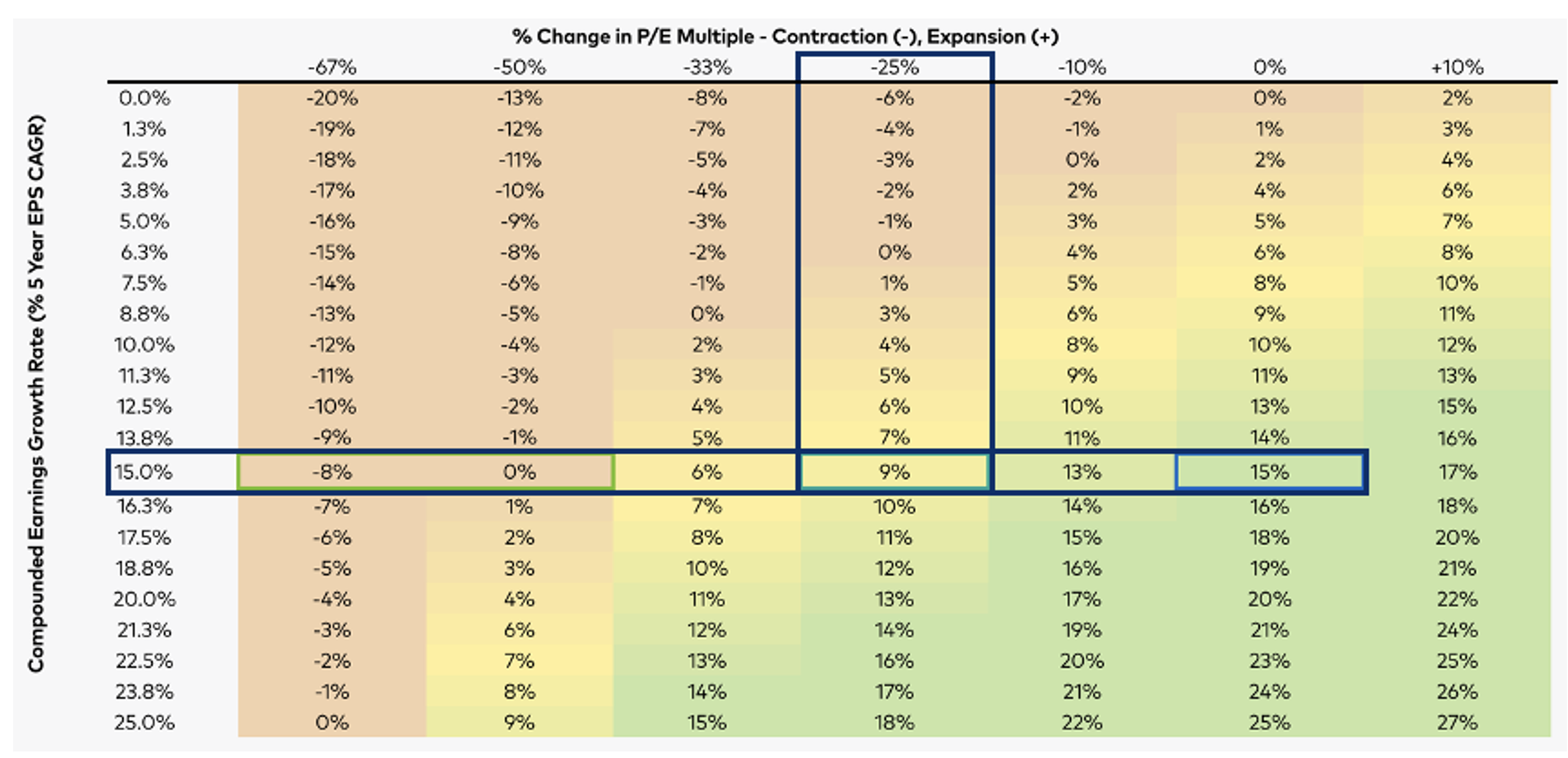

Longer-term equity investors, however, shouldn’t fear further declines. As I have demonstrated previously using Table 1, which is provided again for convenience, investing in companies with accelerating earnings provides a buffer against a further contraction in Price Earnings multiples.

As Table 1 demonstrates, investors holding shares for five years could experience a 50 per cent decline in the P/E ratio of a company growing its earnings per share by 15 per cent per year before they see losses. The earnings growth provides a buffer against contractions in P/E ratios.

Table 1. P/E and EPS growth reconciliation

Source: Polen Capital

Reading Table 1 begins by selecting a rate of earnings per share growth over five years from the Y-axis. Begin by choosing the 15 per cent row. Now move across to the column headed ‘minus 25 per cent’. Next, move down that column to the item intersecting with the 15 per cent row. The 15 per cent row and the -25 per cent column intersect at 9 per cent.

Nine per cent is the compounded annual rate of return an investor receives if they invested, for five years, in a company growing its Earnings Per Share by 15 per cent per annum, and the P/E ratio of the shares contracted by 25 per cent after their purchase.

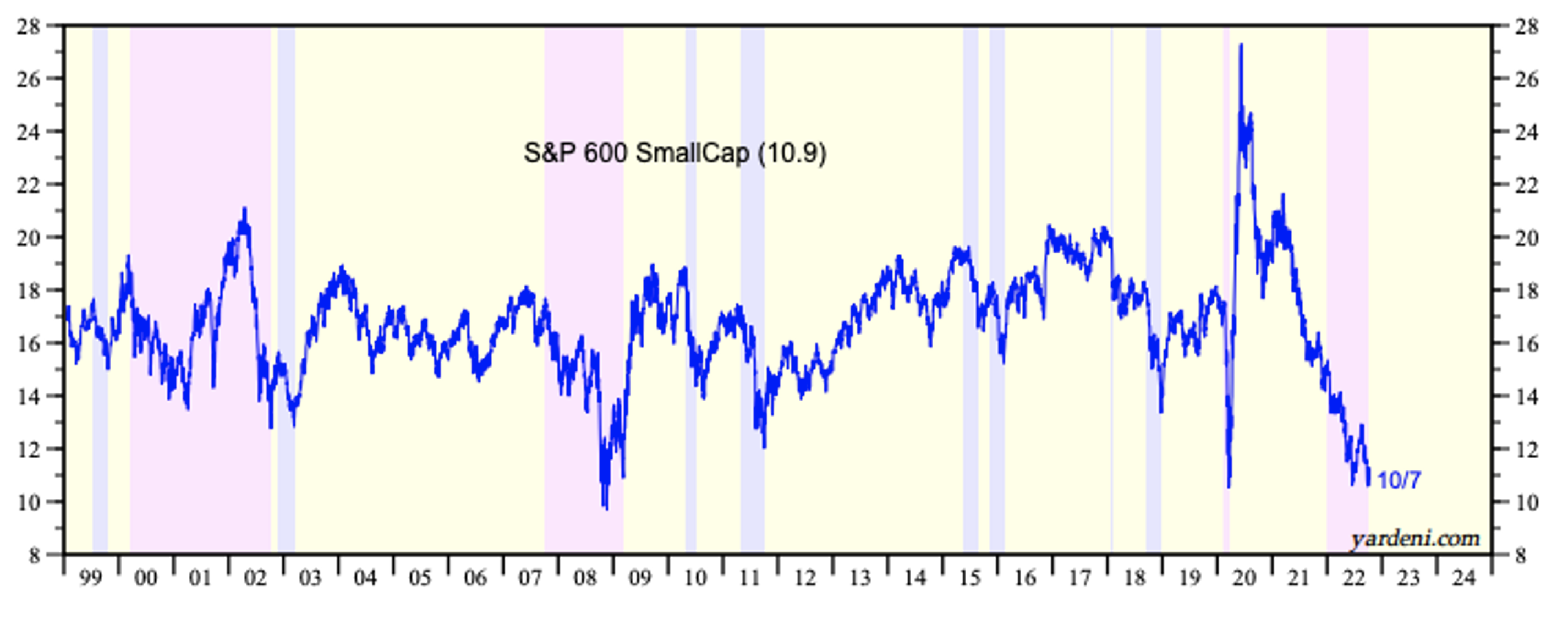

With P/E ratios today at levels unseen since the COVID sell-off and the Global Financial Crisis before that, I am relatively unconcerned about a further contraction in P/E ratios.The significant P/E contraction thus far (Figure 1.) appears to have accounted for that which is known: additional rate rises, peaking-but-sticky inflation and a possible recession.

Figure 1. P/E contractions, especially for small caps have already been severe

Source: Yardeni

Despite the mouthwatering prices on offer right now, investors aren’t salivating at the compressed P/E ratios on offer because they fear something else.

Investors might reasonably be concerned about a fall in the ‘E’ in the P/E ratio. A recession could inspire a decline in earnings, so we should address the possibility of incomes falling. If P/E ratios stay where they are but profits decline, share prices must fall.

So that brings me to the question of earnings and whether the stock market must fall if profits do.

My first observation, which I alluded to above, is that if we experience a recession, it will be the most obvious in history. Virtually everyone is predicting it. Markets tend to fall dramatically when investors are surprised. Rarely do they collapse when everyone is talking about a collapse.

My second and more attention-grabbing discovery is brought to us by economist Professor Robert Shiller.

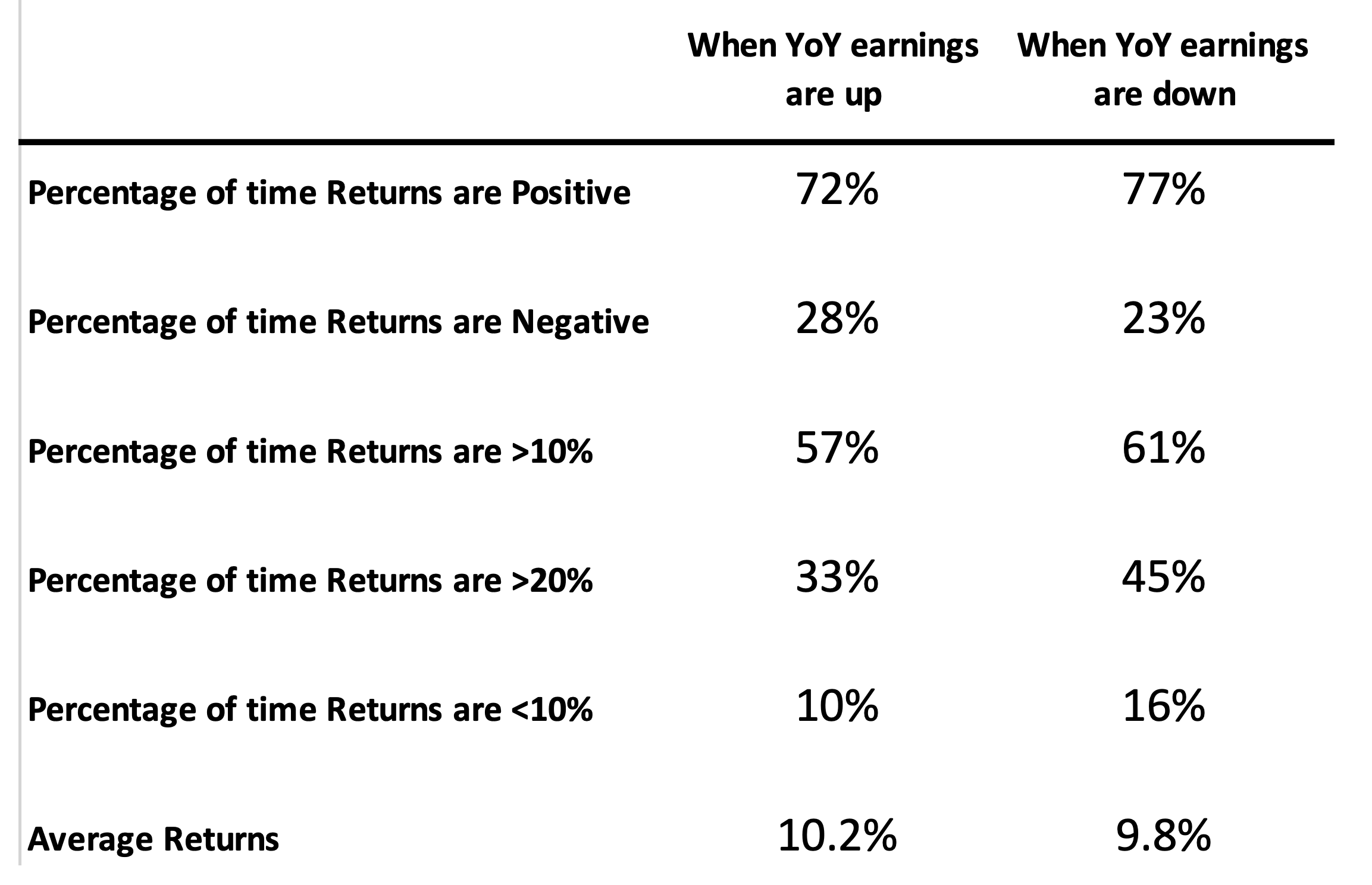

Table 2. Relationship between earnings and the stock market 1930 – 2021

Source: Robert Shiller

According to Shiller, between the beginning of 1930 and the end of 2021, S&P 500 annual corporate earnings growth was positive 61 times and negative 31 times. In other words, earnings grew two-thirds of the time and were shrinking the rest of the time.

Curiously, Table 2 reveals if one only invested in the S&P500 when earnings grew year-over-year (and of course, you couldn’t know this with 100 per cent certainty ahead of time), your average annual return would have been 10.2 per cent on average.

And perhaps counterintuitively, if one were only invested in the S&P500 index when earnings were down year-over-year, the average annual return would be an almost equally respectable 9.8 per cent on average.

Some other surprising findings, revealed by the fourth row, investors over the last ninety-two years were more likely to experience an annual return of more than 20 per cent in years earnings declined.

Less surprising is the observation that over the last ninety years, investors were more likely to experience a decline of more than 10 per cent when earnings growth was negative.

Over the 31 occurrences of negative earnings growth, S&P500 returns were positive 77 per cent of the time and negative 23 per cent of the time. And over the 61 occurrences of positive earnings growth, S&P500 returns were positive 72 per cent of the time and negative 28 per cent of the time.

Conclusion

We know investors have done well buying companies growing their earnings on historically compressed P/E ratios. At Montgomery, and at Polen Capital, your fund managers are focused on companies that are growing earnings and experiencing positive change.

While investors may fear further compression in P/E ratios, Table 1, reveals those fears might be misplaced.

Investors might also fear the possibility of a decline in Earnings Per Share, but Table 2 reveals that concluding another sell-off in the stock market, as a result of declining earnings, may also be a misplaced fear.

The arguments for being greedy when others are fearful continue to build.

gary briton

:

Hi Roger, I think table 2 heading needs amending ‘1930-1921’

All the best

Gary

Roger Montgomery

:

All fixed, sorry Gary