What of China’s imploding economy?

According to several reports, China’s property price index is tumbling. China’s new home prices in 70 cities fell 5.3 per cent year-over-year in August 2024, accelerating from July’s 4.9 per cent drop. This marks the 14th consecutive month of decline and the sharpest since May 2015, despite Beijing’s efforts to stabilise the property market through lower mortgage rates and reduced homebuying costs. The downturn deepened across most major cities, with Beijing (-3.6 per cent vs -3.3 per cent in July), Guangzhou (-10.1 per cent vs -9.9 per cent), Shenzhen (-8.2 per cent vs -8.0 per cent), Tianjin (-1.4 per cent vs -1.2 per cent), and Chongqing (-5.4 per cent vs -4.9 per cent) all seeing further price contractions.

Figure 1., reveals that according to The Bank for International Settlements, China’s real residential property prices are back to where they were almost 15 years ago.

Figure 1. Real residential property prices in China

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve Bank

Nominal prices for China’s top cities have reverted to their levels of eight years ago.

The significance is heightened by the fact China’s residents have parked about 62 per cent of their wealth in residential property. This compares to 23 per cent for Americans, 36 per cent for the Japanese, and 51 per cent for Brits. Chinese exposure to property even surpasses Australians’ 56 per cent.

Understandably, Chinese consumers are refraining from spending, having realised their property hasn’t increased in value for eight years. Meanwhile, anyone who purchased a property after 2018 is nursing losses. This second group have probably pulled their spending altogether.

Chinese President Xi Jinping first introduced the concept of common prosperity at the 10th meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs in August 2021. At the meeting, Xi related common prosperity to raising the incomes of low-income groups, promoting fairness, making regional development more balanced, and stressing people-centered growth. This included a pledge to “reasonably regulate excessively high incomes and encourage high-income people and enterprises to return more to society.”

But Xi’s plan fails to recognise – just as socialism itself has been unable to recognise – under socialism, you eventually run out of other people’s money.

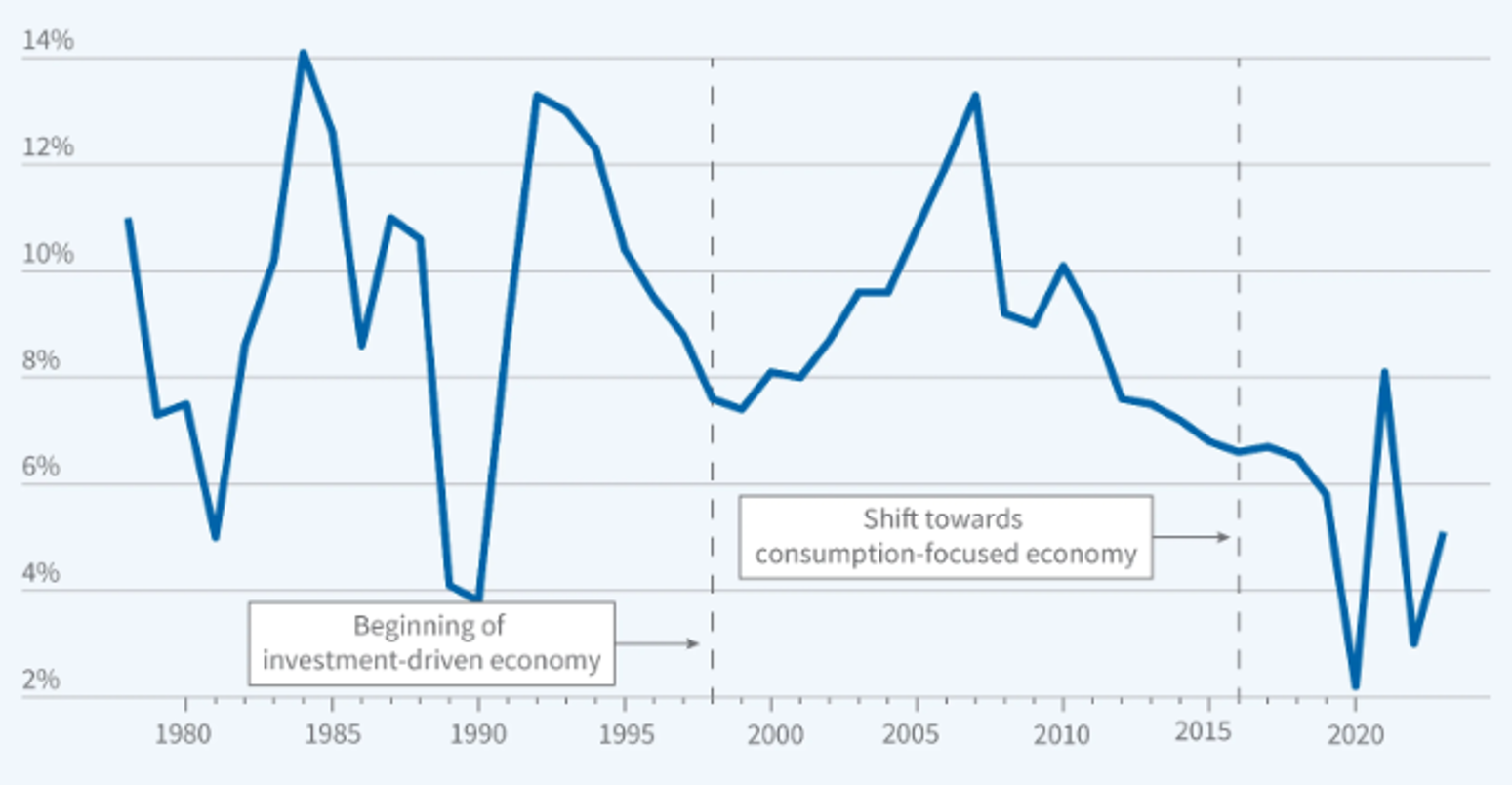

Relying less on leverage and fixed asset investment, and transitioning to a consumer-led economy, requires consumers to spend more. But to do that the property market needs to deleverage the gearing that was built up after the 2014 policy to relax the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio limit for secondary houses primarily used as investments.

Figure 2. China’s annual real GDP growth

Source: “Constructing Quarterly Chinese Time Series Usable for Macroeconomic Analysis,” Chen K, Higgins PC, Zha T. NBER Working Paper 32087, January 2024, and Journal of International Money and Finance 143(103052), May 2024.

That 2014 policy was designed to rectify an overhang in property supply (remember the construction of all those empty cities?) and stimulate housing market activity. The U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research observed, “…as house prices surged, homeowners cashed in capital gains to upgrade to larger primary homes, setting off a positive feedback loop between rising house prices and increased mortgage demand. This feedback loop led to substantial increases in both equilibrium house prices and mortgage borrowing.”

Since then, China has implemented policies to reverse the impact of looser LTVs, the consequence of which has been declining mortgage activity, new property sales and investment, and slumping house prices.

Facing the long-term burden of mortgages held on slumping property, consumers have understandably tightened their belts, and in the process, challenged China’s attempts to transition to a consumption-led economy.

In response, China has lowered the interest rates on ten-year bonds to below two per cent for the first time. It is hoped that just as emergency shorter-term bond rate settings after COVID stimulated developed nations’ housing markets and economies, the same will occur in China.

But when the U.S. and Australia lowered rates to those emergency levels, households weren’t as levered as their Chinese counterparts, and house prices had been rising. In China, the debt is epochal, and house prices have been plunging.

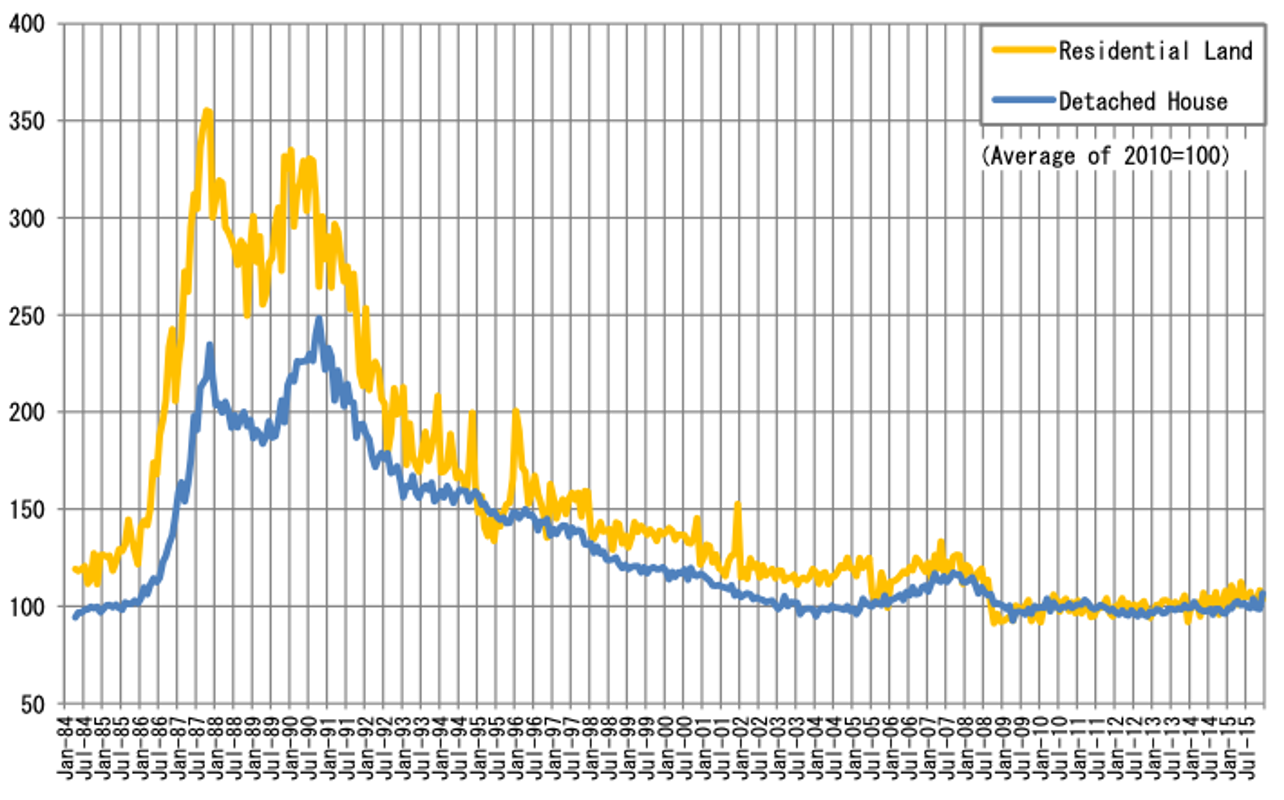

When Japan’s property market burst and required deleveraging, the interest rate was cut from six per cent in 1991 to 0.5 per cent in 1997 and to zero in 2000, but as Figure 3., reveals, it did little to stimulate property prices.

Figure 3. Tokyo Metro Residential Property Price Index (2010=100)

Source: Japan Ministry of Land Infrastructure (MLIT)

China remains a top trading partner to over 120 countries, and it is still the largest trading partner to Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, among many others. While the country’s attempts to become consumer-led are motivated by a desire to be self-reliant, and while its dependency on imports declines, the country continues to rely on foreign demand for its exports.

However, as the global economy continues to stumble through a post-Covid economic recovery, the impacts on China are compounding its challenges. Further declines in growth rates will lead to further declines in demand for raw materials, while slumping domestic consumption will impact a raft of global retailers whose growth aspirations are tied to a burgeoning middle class in China.

Perhaps most importantly, it is vital to remember that dictators can only use two levers to maintain their seats of power: economic prosperity and nationalism. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) promised prosperity in exchange for party dominance, and while it delivered economic growth for decades, that success is now spectacularly faltering. If achieving economic prosperity is deemed a lost cause, the lever of nationalism will be pulled, through the flexing of military might.

Indeed, the flexing is already underway. As the U.S. Department of State notes on its website, “Across much of the Indo-Pacific region, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is using military and economic coercion to bully its neighbours, advance unlawful maritime claims, threaten maritime shipping lanes, and destabilise territory along the periphery of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This predatory conduct increases the risk of miscalculation and conflict.”

Meanwhile, echoing another aspect of Japan’s experience, China’s demographics are deteriorating fast. China’s population of 18-55-year-olds has been declining for seven years, and this cohort is the most likely to be conscripted. A declining population of soldiers may feed the CCP’s insecurities about the economy and tempt action.

During lulls in individual company announcements and trading updates, investors are right to focus on the U.S. Federal Reserve and its interest rate settings. Still, some attention should be directed to developments in China, its economic conditions and its increasing military aggression.