What kind of investor are you?

One of the features of active equity investing is its zero-sum nature (in aggregate). By that, I mean that when an investor “beats” the market, some other investor must get beaten. Averages being what they are, there needs to be an equal representation of investors who deliver above average performance and investors who deliver below average performance.

For investors who aspire to be in the above average category, an interesting question arises: where is the other side of my outperformance? Who is going to be selling to me stocks that are priced cheaply, and buying from me stocks that have become overpriced?

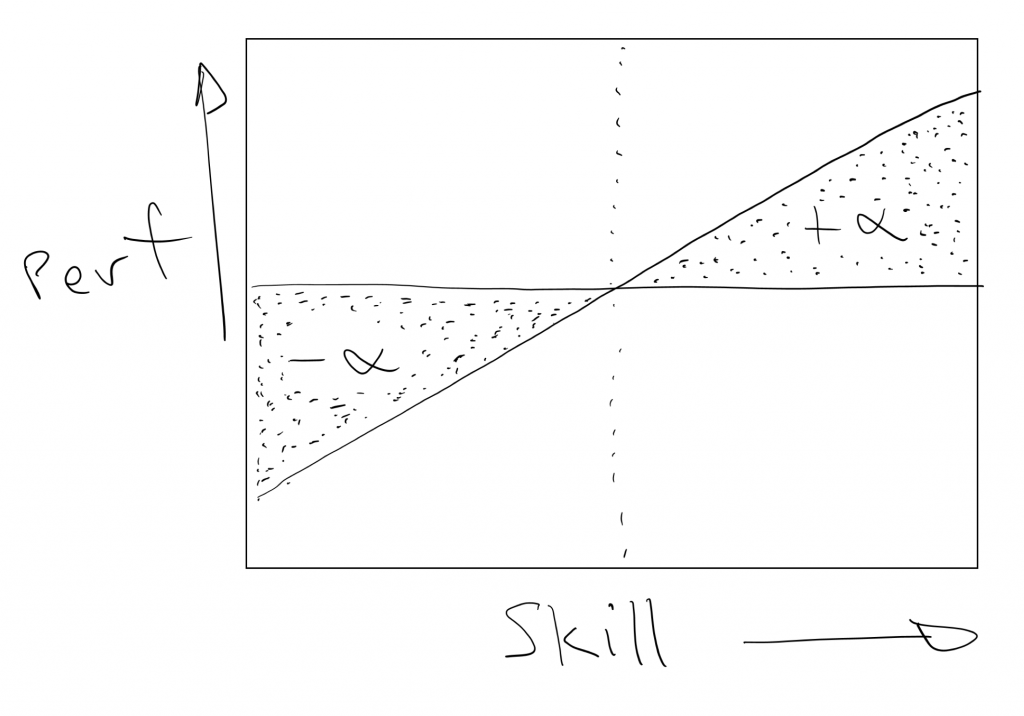

We associate investment skill with outperformance (at least over long stretches of time), and so it is instructive to think about how skill maps to outperformance. Viewed in these terms the investment world probably looks something like the following, with the most skilled investors delivering high levels of alpha, and the least skilled investors balancing the equation, with a corresponding amount of negative alpha.

But here’s where it gets interesting. It is possible to achieve an average result (ie zero outperformance/zero underperformance) with zero skill. Investing in the market index will achieve this, and a group of investors who throw darts at a dartboard will – on average – achieve this result as well.

So, the investors in the negative alpha category need to have, in effect, negative skill. The idea of negative skill is an odd one. “How is that possible?” you may well ask.

The way it happens, I think, is because of systematic errors that can be caused by our inherent behavioural biases. A good example would be the investor who invests in the latest hot stock to avoid missing out, and who panics and sells out when the market tanks. Research in the US by DALBAR (www.dalbar.com) has shown that this type of systematic error is a big problem for investors in US mutual funds, who tend to tip money in when their manager has had a good run, and pull money out after they have a bad run, locking in a pattern of “buy high/sell low”.

This recognition of what drives negative alpha I think tells you something about how you can put yourself in the positive alpha category and answer the question we posed in paragraph 2. At a minimum, you need to recognise and remove the effects of behavioural bias in your own decision making, but ideally, you should position yourself to exploit bias in others by doing the exact opposite of what your instincts tell you to do.

Warren Buffet figured this all out long ago and found a far more concise way of expressing it:

“Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful”.

But he didn’t have a nice diagram to illustrate the point.

When an investor “beats” the market, some other investor must get beaten. Where is the other side of my outperformance? Share on X

Also worth remembering that it is highly unlikely that the number of investors on each side will be equal. One investor beating the market by a lot may be balanced by more than one investor each getting beaten by a little. Or vice versa.