We need to wake up… and get back into bed!

Today’s investors are focused on interest rates, inflation and earnings. A small group are thinking about the issues that could surface in two or three years, such as China annexing Taiwan and the consequences of artificial intelligence’s (AI) birth. An even smaller group are thinking about what lies beyond that.

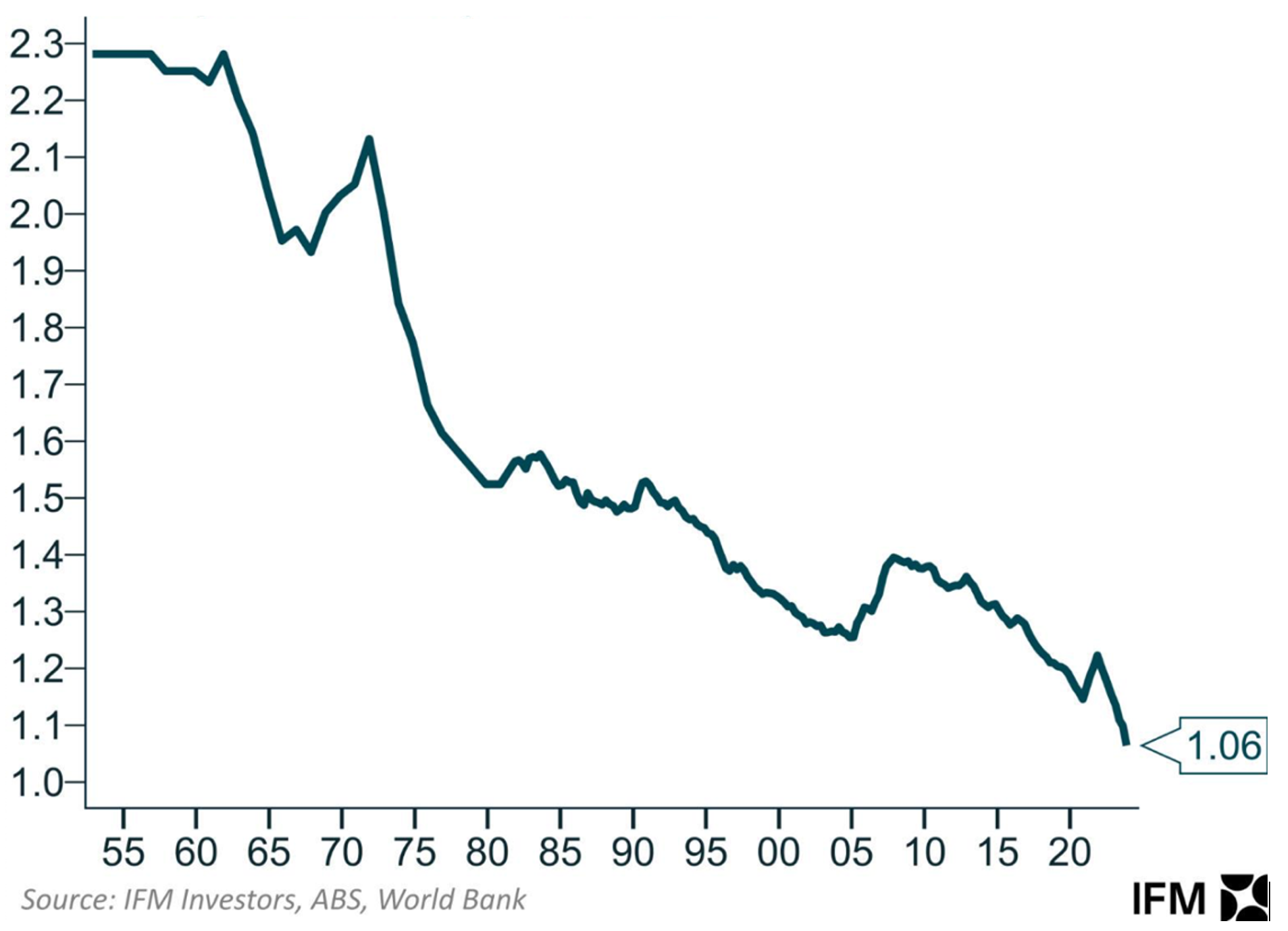

One long-term issue worth bringing to everyone’s attention is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Australia’s birth rate: births per 12 months per 100 of estimated residential population

The birth rate, or the total fertility rate (TFR), is the number of registered births per woman. As Figure 1., reveals, Australia’s is plunging. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in 2023, Australia’s fertility rate stood at 1.5. We are all having fewer kids than in years gone by.

Another statistic is the net reproduction rate, which is the average number of daughters surviving to reproductive age per woman. According to the ABS, this number sat at just 0.72 in 2023, down from 0.9 a decade earlier. A net reproduction rate of one means that each generation of mothers is having exactly enough daughters to replace themselves in the population. A number less than one indicates the reproductive performance of the population is below replacement level.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the “replacement rate” is 2.1 births per woman.

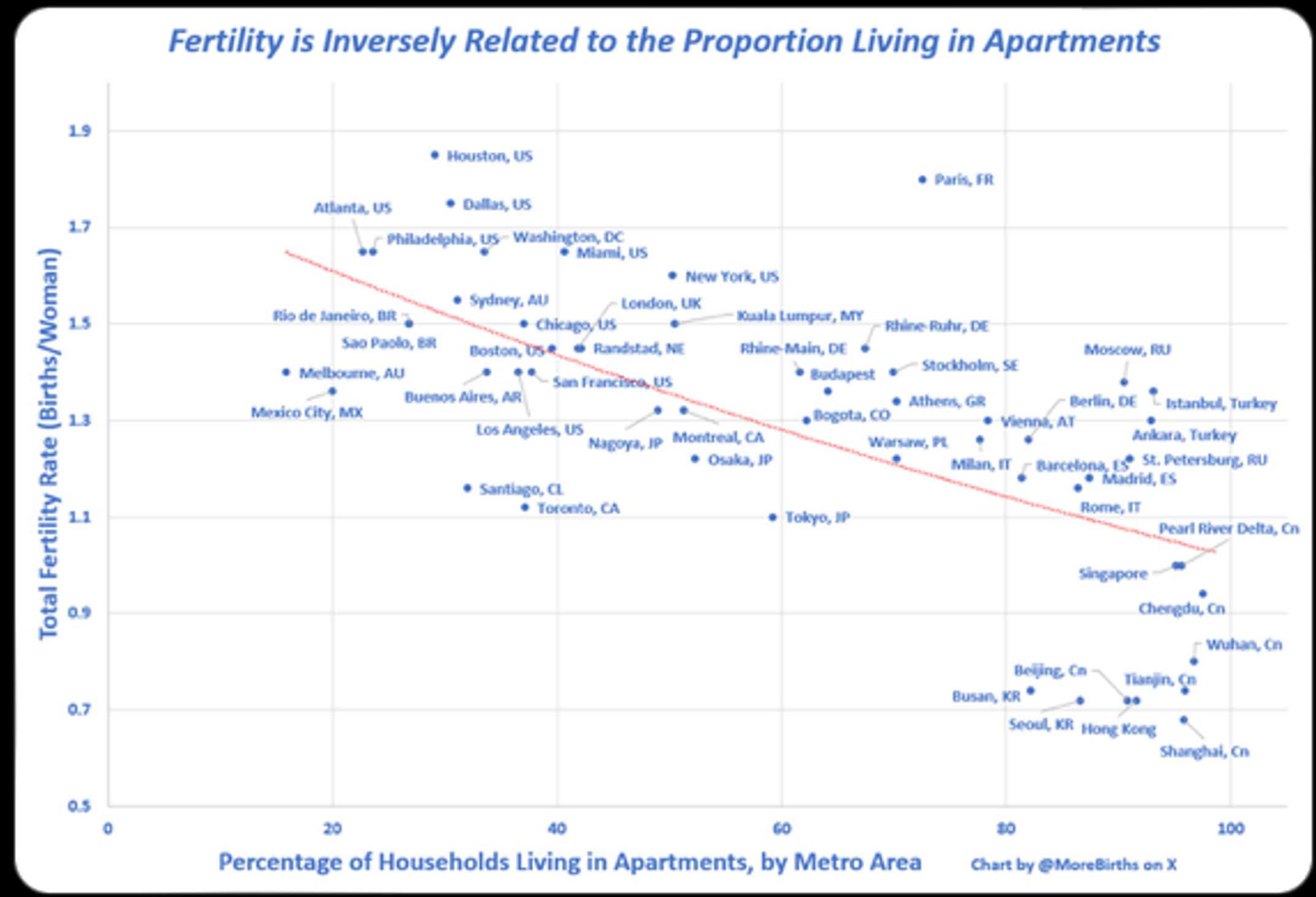

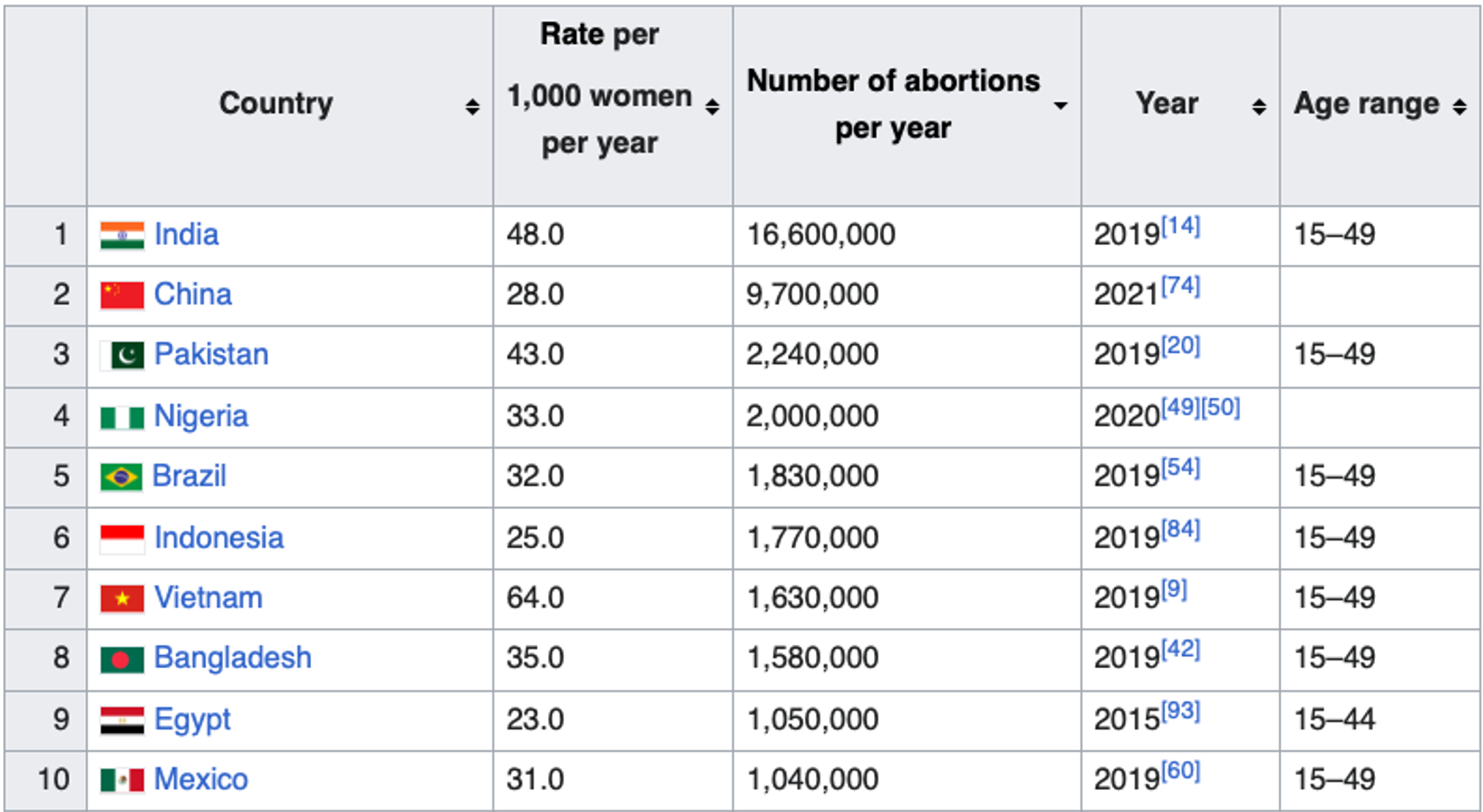

We can point to a range of reasons why the fertility rate has declined, such as careers clashing with family formation, the rise of the gig economy, the increased age of first-time mothers, societal expectations and trends regarding living arrangements, marriage and parenthood, equality, cost of living and the need for dual incomes, cost of education, rising rates of abortion, the success or otherwise of assisted reproduction, inadequate childcare policies, access to mortgages, housing availability and even the rise of apartment living.

Figure 2. More apartments = less babies. Inversely related.

Source: X

Source: X

Table 1. Top 10 countries by annual abortions

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

The UNFPA Technical Division, Population and Development Branch’s 2019 paper, Policy responses to low fertility: How effective are they?, noted, “Such low period fertility rates are not explained by very low fertility preferences. Women, men and couples in countries with very low fertility typically desire to have two children, and their average intended family size is around or above two births. Very low fertility rates signal that there is a wide gap between fertility aspirations and actual family size. This gap tends to be larger for highly educated women, who find it more difficult to combine their career with their family life and aspirations.”

The UNFPA report also alluded to apartment living’s impact indirectly, noting, “In times of women’s massive post-secondary education and labor force participation on the one hand and rising individualistic aspirations on the other hand, the inability to combine paid work with childrearing often results in childlessness or having one child only. This is closely connected with persistent gender inequalities in housework division: for decades, societies with strong traditional gender role norms have been continuously witnessing very low fertility. More recent factors contributing to fertility decline include the trend towards intensive parenting as well as labor market uncertainty and instability coupled with soaring housing prices.”

Living in metropolitan areas with expensive housing markets is linked to a delay of first births by three to four years compared to the housing markets with the cheapest housing.

Whatever the reason for declining birth rates, the consequences may be severe (at least from an economic and social perspective).

Australia, like many other countries, is well on the path Japan has been experiencing for many years. Last year, Japan’s fertility rate stood at 1.2, and in its capital city, Tokyo, it is less than one. According to Japan’s government, the number of babies born in Japan has fallen to the lowest level since records began being collected in 1899.

According to the UNFPA, sub-replacement fertility has spread around the world over the last thirty years. As of 2019, fully one-half of the global population lived in countries where the period TFR is below 2.1 births per woman. East Asia, Southern Europe and parts of Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe reached “ultra-low” fertility rates, with the period total fertility at 1.0-1.4 per woman born in the mid-1970s.

SO WHAT?

While many believe there are enough people in the world, and we shouldn’t be too worried about shrinking working age populations given the threat of a nuclear conflict, AI-related job losses, and humanity’s impact on the environment, the truth is the consequences for individual countries are financially significant.

If the number of people born in any country in the 1970s has fallen to just a quarter of that number today, the problem is that in twenty years each working age individual will need to be productive enough to support four retired people.

Countries with declining working-age populations face a myriad of significant financial consequences. As families have fewer children, they concentrate their investment in the children they do have. We are all familiar with the tiger parenting style of China, Japan and South Korea. There, parents compete to enroll their children in the best schools and pay for rigorous tutoring from a very young age resulting in higher levels of stress, anxiety and mental health concerns among children and parents. Other consequences include:

- Labour shortages: A smaller workforce can lead to shortages in key industries, resulting in reduced production and output, and increased wages as employers compete for limited talent. This can drive up operational costs for businesses.

- Decreased economic growth: A shrinking workforce can lead to reduced productivity and economic output, potentially slowing gross domestic product (GDP) growth over time.

- Increased dependency ratio: With fewer workers supporting a growing elderly population, the ratio of dependents (young and elderly) to the working-age population increases, straining social welfare systems and public finances.

- Higher tax burden: Governments must raise taxes to fund pensions and healthcare for the aging population, which can discourage investment and economic activity.

- Reduced consumer spending: A smaller workforce enduring higher taxes may lead to lower overall disposable income levels, resulting in decreased consumer spending, which is crucial for economic growth.

- Pension system strain: Many countries rely on pay-as-you-go pension systems, where current workers fund retirees. A declining workforce can jeopardize the sustainability of these systems, leading to potential reforms or cuts.

- Increased healthcare costs: An aging population typically requires more healthcare services, leading to higher public and private healthcare costs, which can further strain government budgets.

- Shift in economic structure: As the workforce declines, there may be a shift toward automation and technology adoption, which can have mixed effects on employment and productivity. And while automation may be cheered by producers and businesses, they need to remember they have far fewer cashed-up customers to sell their goods to.

- Investment challenges: Countries that haven’t developed policies to deal successfully with falling birth rates face challenges in attracting foreign investment.

- Regional disparities: Declining populations may not affect all regions equally, potentially exacerbating economic inequalities and leading to urban-rural divides.

Several countries are currently facing significant challenges due to declining working-age populations. Japan, for instance, grapples with a rapidly aging demographic and one of the lowest birth rates globally, leading to severe labor shortages and increased healthcare costs. Germany and Italy share similar concerns, with Germany attempting to attract skilled immigrants to counter its shrinking workforce, while Italy’s low birth rate contributes to economic stagnation and pressures on public services.

In Asia, South Korea is witnessing a dramatic decline in birth rates, raising fears of future labour shortages and economic growth challenges despite government incentives to encourage family growth. Meanwhile, Russia’s declining birth and high mortality rates, compounded by external sanctions, have resulted in a shrinking population. Eastern European countries like Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria also struggle with population decline due to low birth rates and emigration, further exacerbating labour shortages and economic difficulties. Spain, too, faces challenges from its aging population and low birth rate, impacting its pension and healthcare systems.

These countries are exploring various strategies, including immigration policies and family support measures, to mitigate these demographic effects.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

It’s not all bad news, provided the policy response is comprehensive rather than piecemeal.

Figure 3. TFR in Czechia, Russian Federation and Sweden 1970-2018

Source: UNFPA

Source: UNFPA

As Figure 3., reveals, the impact of family expansion policies can be positive. The Czech Republic commenced a series of reforms in 2001 and in the following decade period TFR rose. Much of the upswing was due to a shift towards earlier childbearing and shorter birth intervals boosting the period TFR.

High-quality and easily accessible public childcare, especially for children below age three, is crucial for supporting work and family reconciliation and children’s development. It is an important policy measure that may support fertility decisions of dual-earner couples. Childcare provision influences not only fertility timing but also the completed family size.

Quality of care, which includes a lower number of children per teacher, group size, education of teachers, curriculum, and safety as well as its costs and opening hours are other elements of a “good childcare system”, which may stimulate fertility.

According to the UNFPA report, “One of the largest recent expansions of childcare took place in Republic of Korea, where a dynamic increase in childcare provision was enabled by a huge rise in government spending on childcare, jumping from 0.1 per cent of the GDP in 2000 to 0.9 per cent of the GDP in 2014. This spurred a rapid growth in the number of facilities, especially those run by private companies and parents’ associations which now account for 85 per cent of childcare facilities in the country. As a result, enrollment in childcare between 2005 and 2014 went up from 9 per cent to 36 per cent among children aged 0-2 and from 31 per cent to 91 per cent among children aged 3-5.

A similar reduction in the rate of fertility decline was experienced in Norway when that country expanded its childcare coverage from just 5 per cent of children aged 3-4 years in 1970 to over 90 per cent in 2016. In Norway’s case government funding was not limited to public kindergartens. The country’s goal was full coverage and subsidies to public and private childcare institutions became almost equal. Can you imagine that in Australia? There’d be rorts, frauds and corruption! Expansion needs to be accompanied by very strong regulation.

Figure 4., Simulated completed fertility (by age 35) among women in Norway born in 1957-62 by level of childcare availability for children aged 0-5

Source: Engel et al. (2017); OECD (1999), Rindfuss et al. (2010), and Statistics Norway (2018).

Source: Engel et al. (2017); OECD (1999), Rindfuss et al. (2010), and Statistics Norway (2018).

Figure 4., reveals Norway’s success.

Better and more childcare is just one of the policy ingredients required to boost fertility. Parental leave systems should be positively related to women’s and couples’ fertility decisions as they allow parents to take a break from work to care for their young child without having to terminate their employment contract. Parental leave that can be shared between mother and father.

In Estonia, parental leave with a benefit amounting to the full salary during the year prior to childbirth is extended for 18 months, and since 2008, parents who space their births closely together (within 30 months) can retain the same level of leave benefit without returning to the labour market in between. These are very different to the rather crude ‘baby bonuses’ Australia promoted in 2004 to 2014.

Parental leave provides a guarantee for parents that they are able to return to their work position, which reduces their uncertainty regarding future employment. Importantly, if the timing of firstborns is important, policies should discriminate and be biased towards encouraging younger mothers, which leads to larger family sizes. Policies that continue to reward subsequent births must also be biased to those that met the earlier first-born criteria and reward those who have a second and third child within a relatively short period of time.

The Swedish incentive program was referred to as the ‘speed premium’ and boosted fertility rates from 1.61 in 1983 to 2.14 in 1990. But in that country poor subsequent economic conditions produced a roller coaster effect that reflected the business cycle. In Estonia fertility also dropped again as the economy entered its recession between 2010 and 2013.

Clearly, it is essential that a vital and robust economy is maintained lest parents defer childbearing. Indeed, it is vital for future parents to have a job to accumulate resources before parenthood and to support their family and children later in life. Countries with high unemployment and high instability of employment contracts have lower fertility. It is also essential for parents to combine employment with family life. This is complex. While the availability of adjustable hours and part-time roles can have a positive effect on fertility, part-time employment will not stimulate fertility if it is of worse quality than full-time employment in terms of job protection, social benefits or hourly earnings. And often part time programs are designed to allow mothers to balance work and childcare but the long hours worked by men has a detrimental impact on fertility.

As the UNFPA report notes: “This negative influence is particularly large for the highly educated women: the authors estimated their completed fertility at 1.8 in countries where men work on average 38 hours per week and around 1.45 in countries where men work 45 hours on average. Strengthening working time regulations in order to reduce overtime, shorten the working hours and introduce more flexible working time for men (and not only for women) may thus make it easier for couples to have children, in particular in long working hours cultures.”

The report’s conclusion is that single policy measures are unlikely to increase fertility, especially when they are modelled on outdated assumptions about families and gender roles. Meanwhile, the report details Sweden’s, France’s and Germany’s successful implementation of comprehensive packages.

If Australia and others are going to arrest the decline in the respective fertility rates (and do more than just increase immigration, which brings with it some elements of societal discord), they need to develop and implement comprehensive solutions now. That must include, affordable houses (not apartments) for Australians actually having children, comprehensive coverage by affordable childcare, and generous and expensive parental leave for both or either parent. Without appropriate measures and ongoing bipartisan support, the consequences are already plain to see.

The full 2019 UNFPA report and its suggestions can be found here.