Under pressure

After the RBA’s latest cut to official rates, many investors will be tempted to take some of their money out of cash in pursuit of the high dividend yields offered by our banks. But are these yields sustainable as the banks feel the squeeze from margin pressure and increased liquidity requirements?

Yesterday, the RBA announced another 25 basis point cut to official overnight interest rates to a new record low of 1.5 per cent. This is likely to further fuel demand for income producing assets such as property and companies with high dividend payout ratios as investors attempt to offset the reduction in income on risk free assets by taking on more risk.

One of the sectors that usually draws the attention of yield seekers is the banks. While the banks have not really benefited from the yield trade over the last 12 to 18 months as a result of the perception that increased capital requirements will require a reduction in dividend payout ratios, cuts to the RBA’s official rate are also likely to have a negative impact on future bank earnings.

This is due to two factors.

The first is the impact on the net interest margin generated by banks. The problem for the banks is that as rates fall, it becomes increasingly difficult to recover any reduction in variable lending rates through lower funding costs given that an increasing proportion of the deposit base is already priced at interest rates close to or at zero.

Consequently, the banks are able to increasingly pass less of any incremental RBA rate cuts to their variable lending rates without negatively impacting their net interest margin.

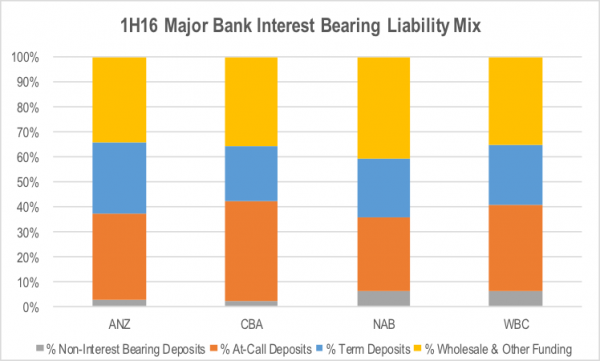

The chart below shows the mix of loan book funding liabilities for each of the major banks at the end of 1H16.

Clearly, the banks are unable to reprice any of the non-interest bearing deposits. Anyone that has looked at the interest rate their at-call accounts earn at present will know there is little the banks can do to reduce the pricing on this source of funding from here. This implies around 35-40 per cent of any reduction in lending rates resulting from RBA rate cuts will have a minimal offset in terms of a reduction in the cost of the bank’s funding.

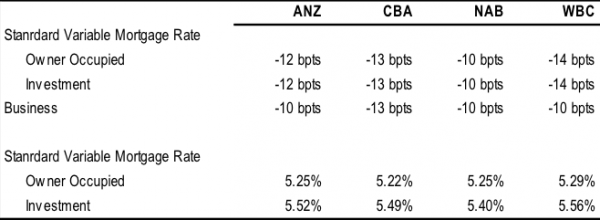

Following the RBA announcement, the major banks came out quickly to announce variable loan repricing. The reduction in variable mortgage and business lending rates were between 10 and 14 basis points, or around half of the RBA’s 25 basis point cut to official rates.

On the surface, it would seem that the net impact of reducing standard variable rates by around half the RBA’s cut would provide a net positive impact to net interest margins, even if the banks cannot reprice any of their non-interest bearing and at-call deposit rates. However, there are a number of other factors to take into account.

The first is that the banks either passed on all or almost all of the last rate cut in May. As a result, net interest margins are likely to have already been under pressure.

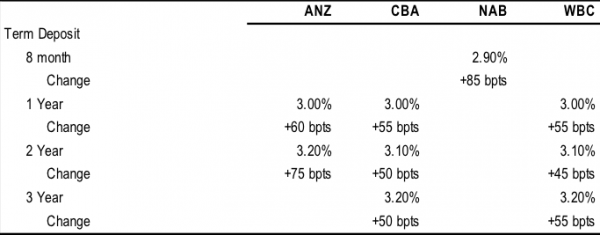

The other point of interest in the announcements from CBA and NAB was a substantial increase in term deposit rates. CBA announced a 50-55 basis point increase for 1 to 3-year term deposit rates, with these rates now sitting well above the new RBA official rate of 1.5 per cent and equivalent bank bill swap rates. These rates were swiftly matched by ANZ and Westpac. NAB announced that it will offer an 8-month term deposit at a rate of 2.9 per cent.

This might look like a strange move given lending rates are falling.

In terms of regulatory risks for the banks, the market has been largely focused on the likely need for the banks to continue to increase the amount of equity they hold against their loan books, negatively impacting their sustainable ROE and dividend payout ratios.

However, there is another regulatory change coming with APRA expected to enforce minimum net stable funding requirement ratios from 2018. This is designed to reduce the risk of a liquidity squeeze on the major banks in the event that wholesale funding markets freeze. The net stable funding ratio requirement will force the banks to reduce their reliance on short term wholesale debt funding in favour of longer term wholesale debt or more stable customer deposits.

The problem is that longer dated wholesale funding is considerably more expensive than short term wholesale funding. As such, a shift in funding mix toward longer dated debt will increase a bank’s average funding cost, and reduce net interest margins. If a bank can increase its share of the deposit market, it will reduce its need to rotate debt into higher cost longer term debt. This could explain the banks’ more aggressive offers in the term deposit market.

We expect that the NSFR requirements will be another point of margin pressure for the banks over the next few years.

Increased liquidity requirements also act as a drag on net interest margins as interest rates fall, given the banks earn a lower rate of return on interest bearing liquid assets held.

Another issue is anecdotal evidence of increasing mortgage front book competition. While this will take time to flow through to the back book, increased front discounting results in downward pressure on net interest margins over a period of time.

Offsetting these factors, lower lending rates should fuel stronger loan book growth. But given the amount of gearing already in the economy, and the limited net reduction in lending rates, it will be difficult for loan book growth to fully offset the impact of the above drivers of margin pressure.

The Montgomery funds own shares in CBA and WBC.

Stuart Jackson is a Senior Analyst with Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Always find your articles interesting. I am a novice investor and can’t see the correlation between the value people are seeing in property or short term stocks and what I see around me. Low wages growth, low inflation… I can see we are all earning a wage with employment high but at what point does everyone say that is not value for money or will just keep going until we lose our jobs.

The marginal price setter of assets like property tends to be someone that is utilising as much debt as they can obtain to determine the maximum price they can pay. Unfortunately basing a person’s debt limit on the current short term rate when the mortgage life is 30 years is dangerous. Thankfully APRA is forcing banks to factor in higher interest rates when assessing a person’s debt capacity. But low interest rate are driving asset prices more broadly simply because the purchaser looks at the monthly funding costs and capitalises them at the prevailing interest rate to determine what price is ‘affordable’. Affordability drives property prices not value. The consumer’s confidence in taking on an extraordinary debt burden to get toehold in the property market is generally bolstered by the recent performance of house prices. But this has been driven by falling interests over the last 25 years. Rate can only fall marginally from here given the funding constraints of the banks. But the higher the price paid for an investment, the lower the future return. Buyers at current prices are locking themselves into a low rate of return going forward. They had better hop inflation and interest rates stay low over the next 30 years.

We hear a lot of comments about how hard it is to save for a deposit to buy a house at current prices. What tends to be forgotten is that people who borrow 80-90% of the purchase price are locking themselves into have to save 5 to 10 times the deposit amount over the next 30 years in order to repay the principle of the loan. And while rent is seen as ‘dead’ money, interest, rates, maintenance costs are no more alive.

So those that are confronted with low wage growth and low inflation are also locking themselves a high level of fixed costs over a 30 year period. That doesn’t leave a lot of room for the inevitable times of economic hardship.