The OECD says core inflation remains persistent in many countries

With forecasters failing to predict the acceleration of inflation from 2021, and its subsequent persistence, it is unsurprising that the U.S. ten-year treasury bonds now exceeds 4.4 per cent, the highest yield recorded in 16 years.

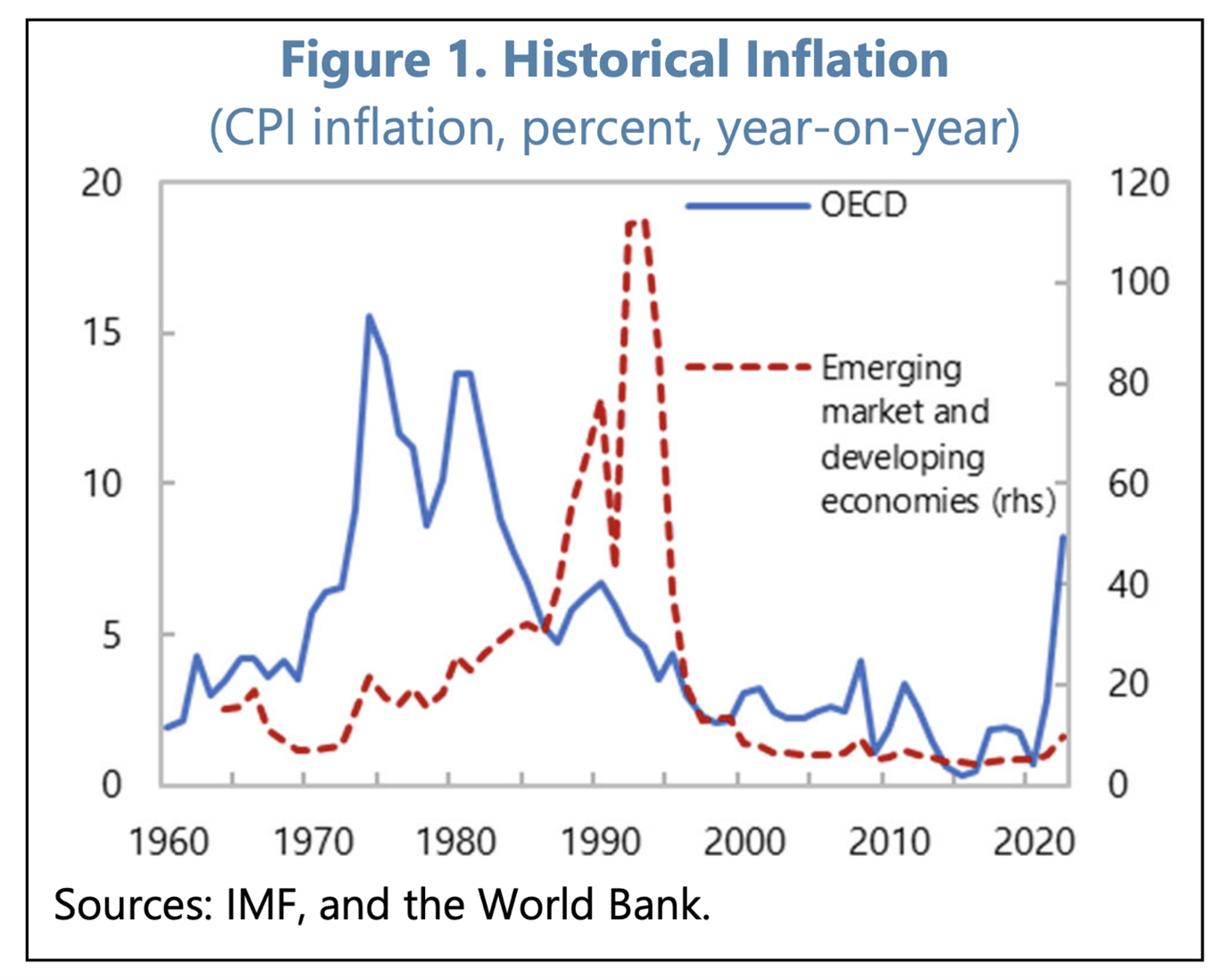

Factors include Russia’s war on Ukraine fuelling an energy and food price shock, strained supply chains from the COVID-19 pandemic, the subsequent faster than expected jump in demand, and the expansionary government fiscal policies.

Government’s budget surpluses have become a rarity – the UK and the U.S. hasn’t achieved one for 20 years; and France hasn’t achieved one for 50 years. Whilst budget deficits have helped to extend economic cycles, inflationary surprises, and debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratios have become a casualty.

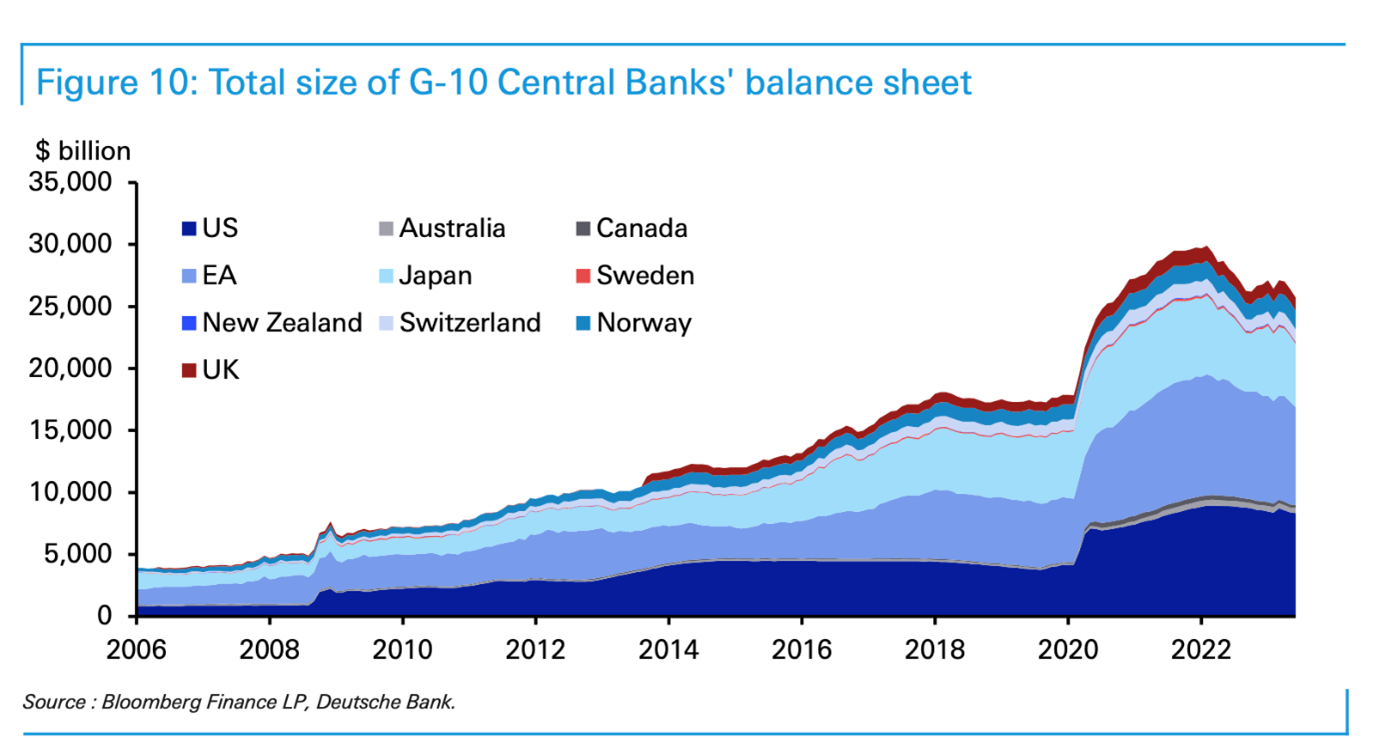

As inflation surged, governments were late in withdrawing their accommodative policies; and many Central Banks around the world belatedly tightened their official cash rates – typically by over five percent in the past 18 months.

The rapid tightening of official cash rates has accentuated the risk of financial instability, and policymakers must be relieved that employment data generally remains very solid. Families are struggling to absorb rising energy, fuel, and food bills whilst the cost of mortgages or rent has gone through the roof.

The question for investors is whether inflation comes down rapidly over the foreseeable future, thus reducing pressure on households through lower costs and interest rates; or whether inflation and higher interest rates persist?

On one side of the coin, Governments are pouring funds into decarbonisation strategies which will buoy demand for metals and minerals traditionally linked to the economic cycle. For example, the close relationship “Doctor Copper” typically had with global industrial production may be less insightful as the world builds non-fossil fuel infrastructure. Other pressure on budget deficits are coming from the expenditure on higher interest charges, ageing populations, and defence. Will the celebrations of beating inflation prove premature, implying interest rates will be required to stay “higher for longer”?

On the other side of the coin, China is trying to transition from an economy reliant on investment and property to one on consumption. How this plays out is anyone’s guess, but it could see some disinflationary influences.

Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has marginally downgraded its forecast economic growth rate for Australia to 1.8 per cent in calendar 2023 and 1.3 per cent in calendar 2024, close to an extended GDP recession on a per capita basis.