The history of organised trading in marketable securities

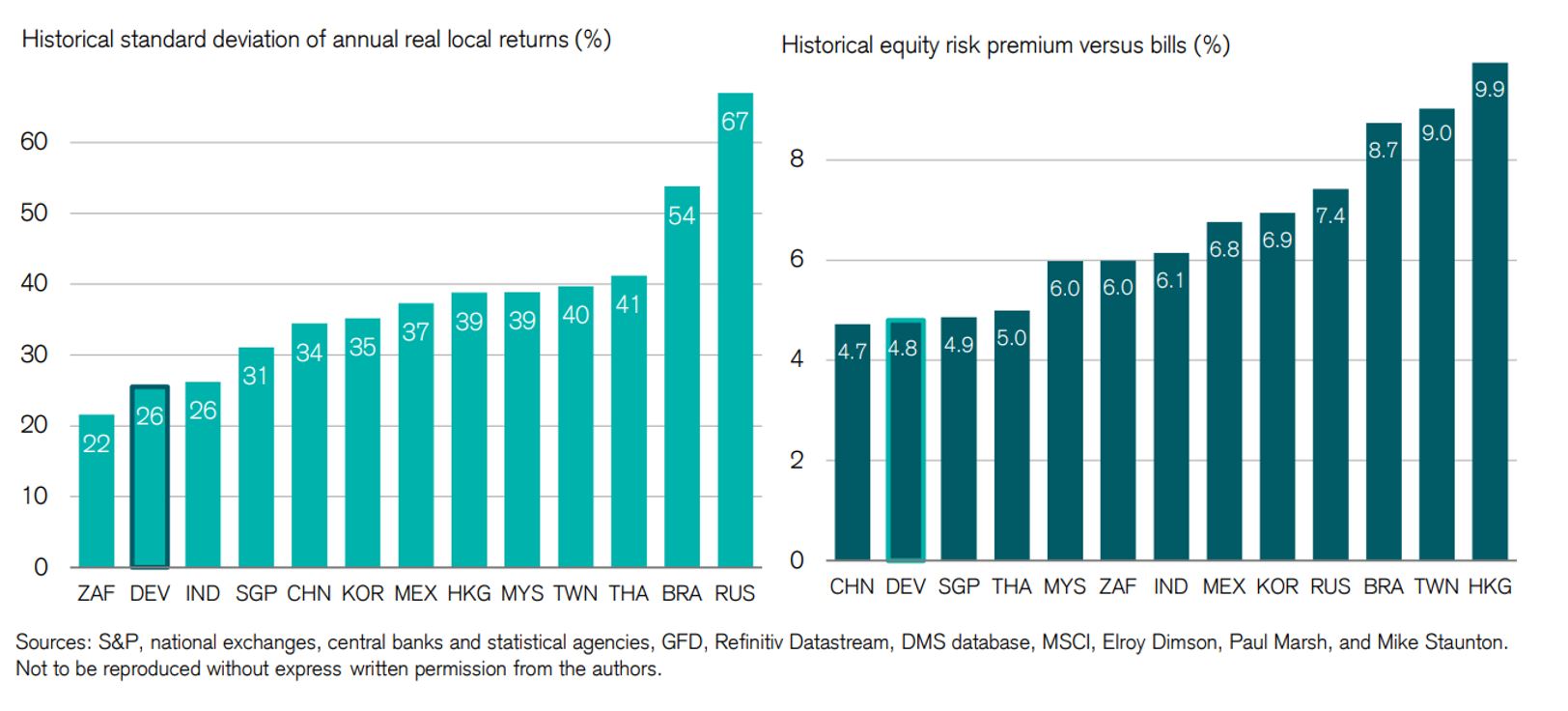

Organised trading in marketable securities began in Amsterdam in 1602, London in 1698 and New York in 1792. Fast forward to both 1900 and 2021, and stock-markets were a very different place. In 1900, the top four markets represented 56 per cent of world market capitalisation. These were the UK representing nearly one-quarter of world capitalisation (4 per cent today), the USA representing 15 per cent (56 per cent today), France representing 11 per cent (3 per cent today) and Russia 6 per cent (0.3 per cent today).

Relative sizes of world stock markets, end-1899 (left) versus start-2021 (right)

In the 2021 Credit Suisse Yearbook, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton from the London Business School pointed out “At the start of 1900 virtually no one had driven a car, made a phone call, used an electric light, heard recorded music, or seen a movie; no one had flown in an aircraft, listened to a radio, watched TV, used a computer, sent an e-mail, or used a smartphone. There were no x-rays, body scans, DNA tests, transplants, or antibiotics.”

In the 2021 Credit Suisse Yearbook, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton from the London Business School pointed out “At the start of 1900 virtually no one had driven a car, made a phone call, used an electric light, heard recorded music, or seen a movie; no one had flown in an aircraft, listened to a radio, watched TV, used a computer, sent an e-mail, or used a smartphone. There were no x-rays, body scans, DNA tests, transplants, or antibiotics.”

New industries that have formed since this time include electricity and power generation, motor vehicles, aerospace, airlines, telecommunications, oil and gas, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, computers, information technology, media and entertainment.

Over 121 years, the growth of the US market reflects its superior relative economic performance, large volume of new listings on the stock exchange, innovation excellence and substantial returns from US companies.

Over this period the compound average annual returns in the US were as follows – Equities: 9.7 per cent, Bonds 5.0 per cent, Bills 3.7 per cent and Inflation 2.9 per cent. Hence, the real (i.e. return net of inflation) annualised return of equities versus inflation was 6.8 per cent in the US. As an aside, Australia, which accounts for 2.1 per cent of world capitalisation, has delivered a real annualised return of equities versus inflation of 7.0 per cent).

And what of Russia?

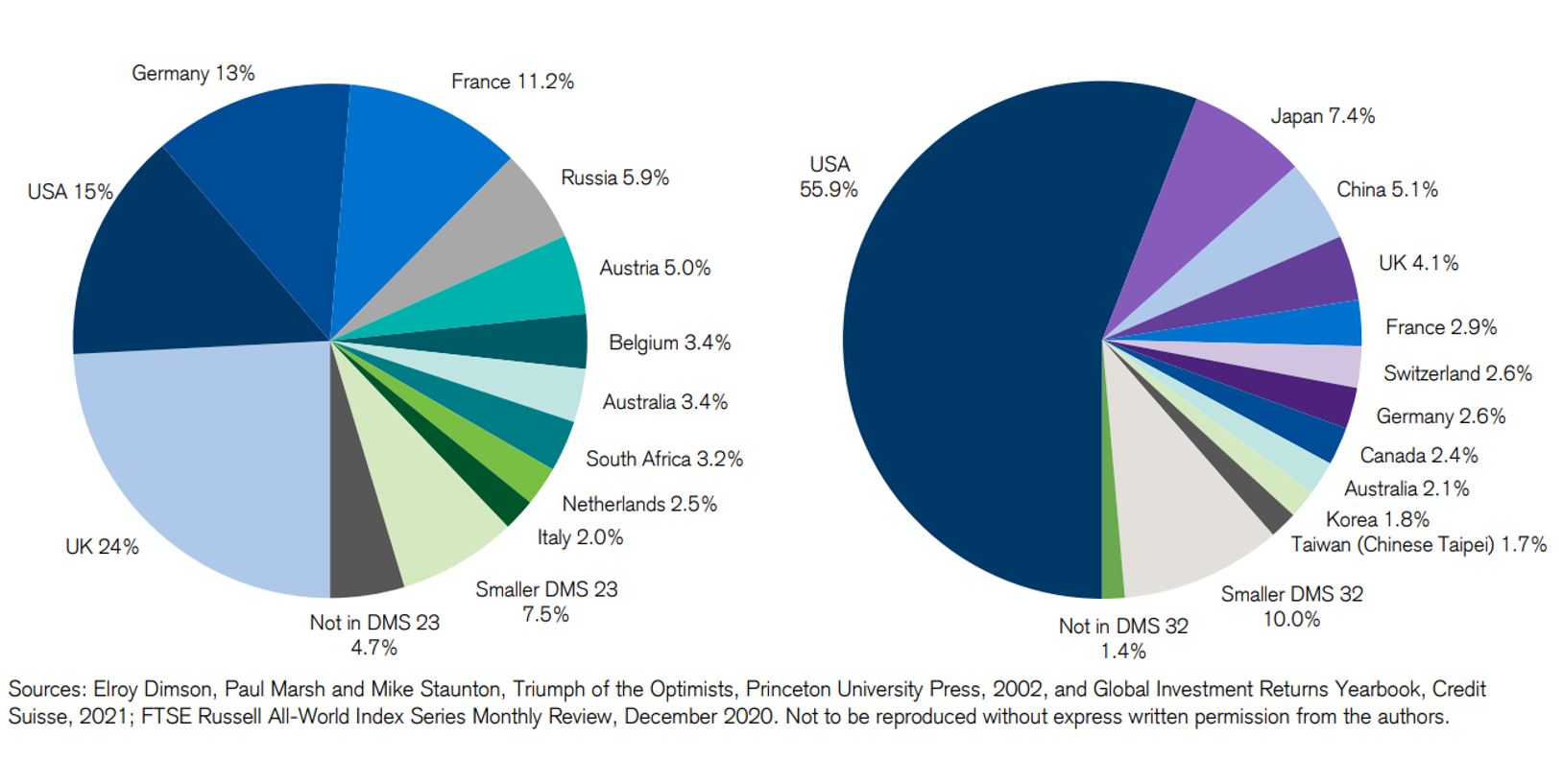

The expropriation of Russian assets in 1917 were “pitched” as wealth redistribution (rather than wealth loss). After their stock exchange re-opened in the early 1990s, it appears much of that redistribution became more finely focused. Despite delivering an annualised real 2.7 per cent equity return (in US$) since then, the volatility of those returns, at an annual 67 per cent, is off the Richter scale. As per the events of 1917, one wonders how much investors will lose 105 years later?

Long-run historical volatility (left) and equity risk premiums (right) from individual markets