The calculus of madness: Part 2

From South Sea to AI: Artificial Intelligence (AI) companies seem to be asking investors the question: Just how long can growth be built on the question of future returns – and a productivity revolution – that are by no means guaranteed?

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 remains the archetype of a financial mania driven by exotic new ‘tech’, the promise of monopoly returns, and limitless public imagination.

At first, the idea of comparing the South Sea bubble to an AI boom 305 years later seemed far-fetched. AI is not, for example, a Ponzi scheme being promoted by those who fail or refuse to publish financials or forecasts of how profits will be made.

Nevertheless, the AI boom displays some of the behavioural hallmarks of bubbles past, including explosive valuation surges, revolutionary but poorly understood technology, aggressive capital raising on nebulous future promises, celebrity endorsements, FOMO-driven retail participation, and a willingness by investors to suspend traditional valuation discipline.

As an aside, Harvard economist Jason Furman recently performed a back-of-the-envelope calculation and found that, without data centres, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) growth would have been just 0.1 per cent in the first half of 2025.

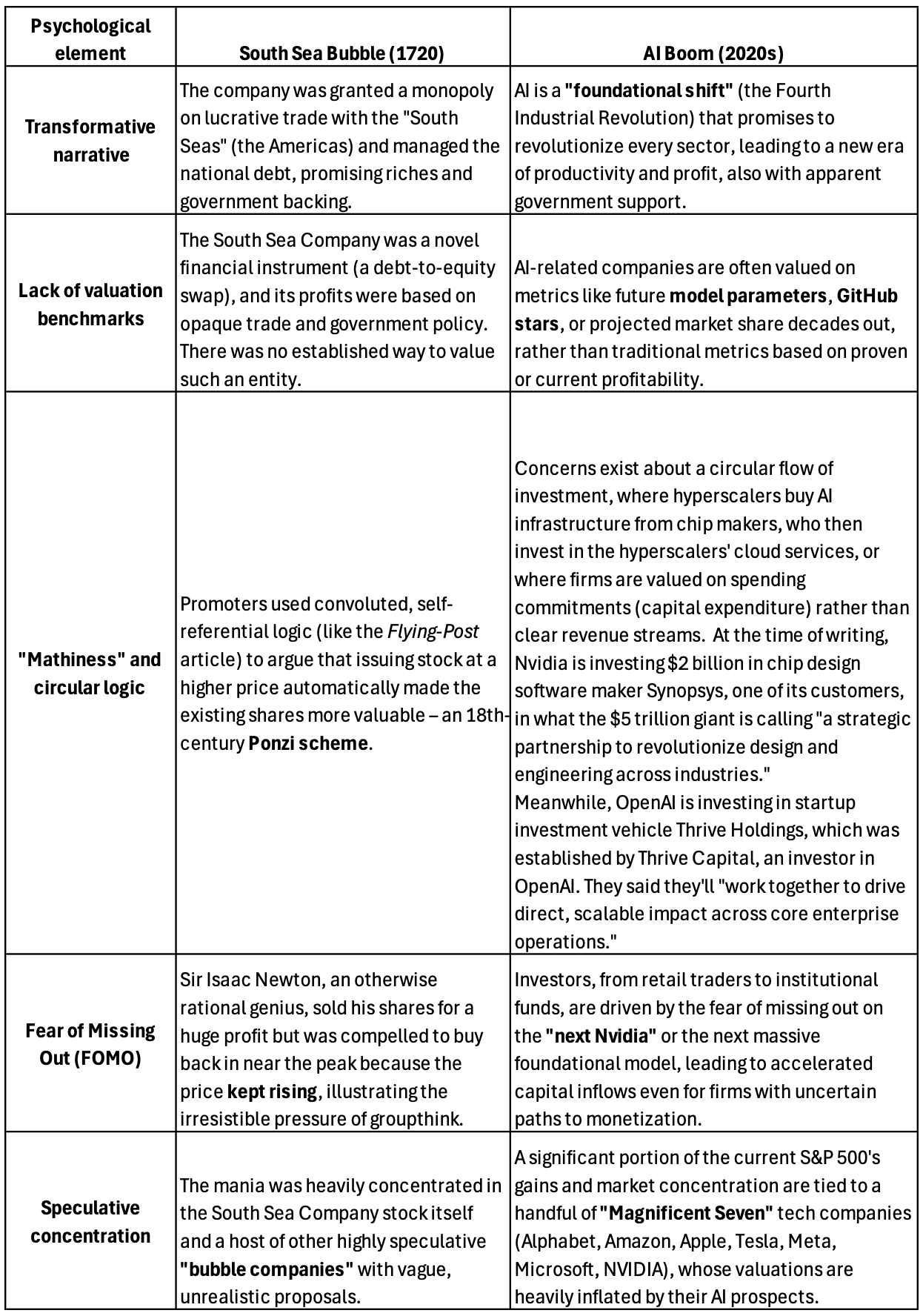

Table 1., is an abbreviated comparison highlighting how revolutionary technology, whether it’s 18th-century global trade monopolies or 21st-century generative AI models, can create a narrative of limitless potential that quickly outpaces measurable economic reality.

Something revolutionary and new, and whose potential outruns comprehension

Something revolutionary and new, and whose potential outruns comprehension

In 1720, the ‘something new’ was the British government’s novel scheme to convert annuities into tradable equity shares via the South Sea Company, combined with the exotic ‘option’ of monopoly trade with South America (a region almost no Englishman had visited). The actual business plan was thin, but the promise of limitless wealth from the Spanish Main (the Spanish-controlled territories and waters in and around the Caribbean Sea and the northern coast of South America) seized the public imagination.

Since ChatGPT’s release in November 2022, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has performed the same role. Large Language Models (LLMs) and image generators appear almost magical to the layperson. Few investors understand the underlying architecture or the enormous ongoing costs of training and inference. Few investors appreciate that AI is nothing like the SaaS (Software as a Service) boom of the 2010s, where companies enjoyed circa 85 per cent gross margins because software was “written once, and sold infinitely.” Few investors understand AI introduces a physical cost to every digital interaction – a single ChatGPT query consumes 10x -15x more energy than a traditional Google search and costs the supplier 500 times more to provide. Despite this, a consensus has quickly formed that AI will “change everything.”

In both cases, the ‘something new’ was real and important, but its economic implications were (and remain) highly uncertain. Despite this, stock prices raced far ahead of any realistic cash-flow timeline.

Monopoly or quasi-monopoly narratives

The South Sea Company was granted a legal monopoly on British trade with the entire west coast of the Americas. Investors extrapolated infinite riches from this charter, despite the inconvenient fact that Britain and Spain were frequently at war.

Analysts routinely describe today’s AI leaders as pursuing a “winner-take-all” or “winner-take-most” market structure due to network effects, data moats, and the enormous fixed costs of frontier model training. Today, the phrase “picks and shovels” (echoing the California Gold Rush) is constantly applied to Nvidia and TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) in the same way that “asiento” contracts (agreements that granted the British South Sea Company the exclusive right to supply enslaved Africans to the Spanish American colonies in exchange for taking on British national debt) were fetishised in 1720 prospectuses.

Explosive capital raising on future promises, not present earnings

The South Sea Company raised money in multiple tranches throughout 1720, issuing new shares at ever-higher prices while lending purchasers the money to buy those same shares. By midsummer, the company had virtually no operating business, yet a market capitalisation exceeding Britain’s entire annual tax revenue.

Today’s parallels include companies with single-digit billions in AI revenue (and often loss-making) achieving market caps of US$1–3 trillion, massive convertible note and secondary offerings (e.g., OpenAI’s repeated nine-figure and billion-dollar rounds at escalating valuations with little revenue transparency), and Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPACs) and post-initial public offering (IPO) secondary offerings that are explicitly justified by “AI optionality” rather than current cash flows.

Celebrity and political endorsement

Isaac Newton, perhaps the greatest scientific mind of the age, as well as politicians, courtiers, and even King George I, subscribed heavily to South Seas script. Indeed, it is reported the King became the company’s official Governor in 1718, which provided a powerful endorsement that helped inflate the stock’s value.

Today, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Jensen Huang, and Sam Altman tweet and billions in market value are created – albeit temporarily. Heads of state (Macron, Sunak, Biden) publicly court AI leaders in the same way George I and his ministers courted South Sea directors.

Proliferation of “Bubble Companies”

The summer of 1720 saw hundreds of joint-stock inchoate or ‘blind-pool’ companies floated for every conceivable (and inconceivable) purpose. The South Seas’ “for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is” remains the most famous prospectus line in financial history.

Today’s equivalent could be the hundreds of “AI-washed” companies adding “AI” to their corporate descriptions and ticker symbols or companies announcing “pivots to AI” with 10-50 times share-price spikes on no revenue change.

Retail mania and new financial instruments

The South Sea Bubble was the first great retail speculative episode, with coffee-house trading, subscription lists, and sword-wielding jobbers appearing alongside new financial techniques such as instalment purchases, options, and forwards.

Today’s equivalents are Robinhood, Reddit’s WallStreetBets, fractional shares, 24/7 meme trading, and the explosive growth of retail options volumes on Nvidia, Super Micro, and others.

Moreover, OpenAI was valued at US$500 billion in its most recent funding round, despite generating just US$4.3 billion in revenue during the first half of 2025 and aiming for US$13.5 billion for the whole year.

On the other hand, Google generates US$400 billion of annual revenue – that’s Open AI’s revenue every 12 days – and is currently valued at US$3.8 trillion.

In other words, Google is trading at approximately 10 times sales, while OpenAI is trading at 50 times. And lest you think the difference is justified because OpenAI’s profits are expected to grow faster, I note that Google’s earnings per share is expected to grow more than 25 per cent in 2026. OpenAI’s losses are expected to grow from US$9 billion this year to US$74 billion in 2028. The company is also not expected to be profitable by 2030 and reportedly needs to raise another US$209 billion to fund its growth plans.

The inevitable catalyst and reckoning

The South Sea Bubble peaked in early August 1720 when the share price exceeded £1,000; by December it was below £100. The trigger was a mix of interest-rate tightening (the Bank of England grew alarmed), margin calls, and the Bubble Act (forbidding the creation of joint-stock companies without a Royal Charter), which, ironically, was intended to curb speculation but instead destroyed confidence.

The AI boom has not yet experienced its 1720 December, but rising real yields in 2024–2025, electricity, water and chip-supply constraints, and the first signs of enterprise caution on AI Return On Investment (ROI) have begun to echo the same emerging caution that undid the South Sea scheme.

Conclusion

The South Sea Bubble and the 2023–2025 AI stock boom are not identical, but both are driven by a breakthrough whose ultimate economic impact is enormous yet highly uncertain in timing and distribution. Both episodes feature a rush to establish proprietary moats, both see traditional valuation metrics discarded in favour of narrative, and both attract a mixture of visionary entrepreneurs, rent-seeking financiers, credulous retail investors, and brilliant minds who (may) temporarily lose their bearings.

Time will tell.