The calculus of madness: Part 1

Sir Isaac Newton is enshrined in history as the saint of rational thought. He decoded the laws of gravity, invented calculus, and parsed the rainbow. Yet, in the spring and summer of 1720, the arguably most intelligent man in the British Empire made a series of financial blunders, recorded for posterity, and so catastrophic they have become a cautionary legend in economic and investment history.

Newton’s entanglement with the South Sea Company serves as a stark reminder: in the face of collective delusion and market mania, even a genius can be led astray.

The mechanics of a mania

To understand Newton’s error, one must understand the vehicle of wealth destruction: The South Sea Company.

Founded in 1711, it was not initially a fraud – as many reports suggest – but a tool for managing British government debt. The scheme allowed creditors to swap their government bills for company stock, which promised regular interest payments funded by the state.

To sweeten the deal, the government granted the company a monopoly on trade with the Spanish colonies in South America – the “South Seas.” While the company did engage in trade (including the appalling business of transporting enslaved Africans), its commercial operations were largely unprofitable in the early years.

However, by 1720, the company proposed a radical expansion: taking over the majority of Britain’s national debt. This triggered the first modern financial bubble. The hype was not built on goods sold or ships docked but on the circular logic of stock issuance.

The genius exits… and re-enters

Newton was no financial novice. We have evidence of Newton analysing individual companies long before Ben Graham did in the United States almost 200 years later. In a letter to his friend the mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, Newton rejected a proposal to invest in a company that Fatio was promoting. Newton reportedly noted the low price of that company’s stock, and the unattractive fundamentals, noting, “rents in Scotland are ill paid & difficultly collected.”

Since 1696, when he was in his mid-fifties, he had also served as Warden, and later Master, of the Royal Mint after leaving his academic post at Cambridge University. He was a wealthy member of the elite, earning over £3,000 a year (putting him in the top 0.1 per cent of earners).

As South Sea shares began their now infamous ascent in early 1720, and at almost 80 years of age, Newton was an early investor. Sensing the market was overheating, he liquidated his South Seas holdings in April 1720, walking away with a profit of roughly £20,000 – a massive fortune at the time. Indeed, at an average inflation rate of 2.16 per cent over 305 years, that £20,000 in 1720 has the equivalent purchasing power (excluding land) of £13.5 million today. With UK land rising at an average 5.7 per cent, a £20,000 stake in British land would be worth £440 million today; the point being, Newton’s profit was considerable.

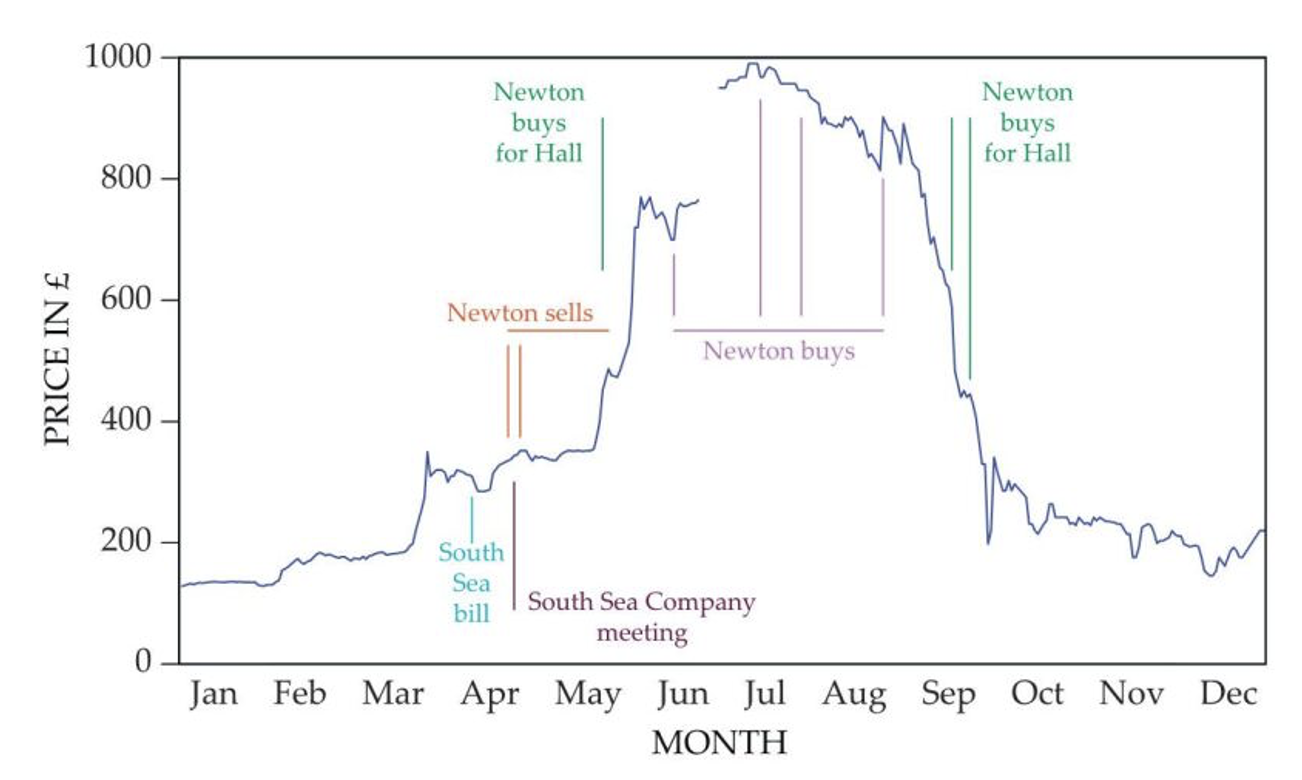

Figure 1. Newton’s Journey on the South Sea

Source: “Newton’s financial misadventures in the South Sea Bubble”, The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, volume 73, number 1 (March 2019).

Figure 1., illustrates the share price of the South Sea Trading Company adjusted for dividends. The horizontal lines depict approximate date ranges for trades, and the vertical lines denote documented transactions and trade instruction dates. ‘Newton buys for Hall’ are trades made on behalf of the Hall Estate, for which Isaac Newton was an executor.

Had the story ended with Newton’s profit, Newton would be remembered as a financial sage. But the bubble kept inflating.

A sophisticated propaganda campaign – reportedly driven by the company – followed the passing of the South Sea Act. The publication of a surfeit of pamphlets and newspaper articles drew in more than 80 per cent of British investors at the time, and included an anonymous article in the Flying-Post that used complex but erroneous quantitative reasoning to promise infinite returns. A letter from a prominent private banker in London, written in June 1720, advised, “When the rest of the world is mad, we must imitate them in some measure.”

The stock price soared. Importantly, however, the South Sea company managers never presented the public with a business plan explaining how they would generate substantial returns for their shareholders. Instead, the logic of the day was essentially a Ponzi scheme: the higher the share price, the more money the company had, and therefore the more the shares were supposedly worth. Sounds a little like today’s Nasdaq-listed Bitcoin treasury company Strategy Inc (MSTR).

Between April and June 1720, and having sold, Newton watched from the sidelines as friends and peers grew fabulously rich. Unfortunately, the psychological pressure of greed’s best friend – the “Fear Of Missing Out” (FOMO) – proved too strong to resist, even for the intellectual dean of physics.

In mid-June 1720, just as the mania was peaking, Newton liquidated his investments in government bonds and poured virtually his entire fortune back into South Sea stock.

The gravity of the crash

The collapse was as swift as it was brutal. In September 1720, the market realized the company’s profit expectations were mathematically impossible. The stock price plummeted. By October, shares were worth less than a quarter of their peak value.

Newton did not sell in time. By mid-1721, he had lost his initial £20,000 profit plus a significant portion of his original capital. While he died a wealthy man in 1727 (with an estate worth roughly £30,000), the South Sea episode wiped out a massive percentage of his net worth.

Why did he fail?

It is easy to label Newton’s actions as simple greed, but an analysis of Bank of England archives suggests a more nuanced psychological failure.

Newton was swept up in a powerful groupthink, which was easier to succumb to then because financial sophistication in the early modern society was low and financial institutions and products were relatively new.

Additionally, it’s possible Newton’s professional brilliance may have worked against him, leading to hubris. As the Master of the Mint, Newton was then arguably the most financially literate scientist in history. He understood currency, alloys, and debt. Yet, he failed to spot the structural flaws of the South Sea scheme because the environment had shifted from economics to mass psychology.

A lesson for the ages

The story of Newton’s foray into trading South Sea shares often concludes with a famous quote: “I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

Whether fictional or not, the sentiment holds true. Newton’s financial disaster illustrates that intelligence isn’t a shield against market irrationality. When information is scarce or abundant, but misinformation is rampant, herd mentality can override the sharpest minds.