Thank cheap money for all the Tech

There can be virtually no doubt that we are in a golden age of technological advances that promise to change the world. From 3D printers churning out both metal objects and human organs, to digital advertising targeting customers based on their moods, and from electric vehicles promising to clean up the atmosphere to the self-described “sharing” economy putting power back in the hands of ‘the people’ (but not holiday-pay or superannuation in the hands of its workers), the technology revolution we are witnessing, and its pace, marks a point in history many of our parents and grandparents could not have imagined.

The question on my mind in recent weeks is how it all came to be? Why is it that we are seeing so much advancement in such a short space of time? Just a few years ago my son received a drone for his birthday; it flew, it took off and landed by itself and it hovered in position if he let go of, or dropped, his controller. Today, just a few years later, drones can follow and film you skiing between the trees, while autonomously maintaining the ideal camera angle and avoiding the trees itself. Meanwhile surf rescuers use drones not only to spot sharks but to locate drowning swimmers and rescue and recover them.

Recently, I was invited to participate in a funding round for an autonomous vehicle project. The technology was simply breathtaking, and like many tech leaders, its founders are praised as visionaries.

But just because technology is great for the consumer doesn’t mean it’s great for the investor. And while it would be comforting to think the pace of advancement we have experienced since the GFC will be maintained forever, we know intuitively it cannot, especially when the technology resides inside companies that aren’t profitable.

That leads me to ask about its source. What has fueled all of the rapid advancement we have most recently witnessed?

The answer of course is abundant cheap money. Confetti money, helicopter money, call it what you like, but ultimately the Ubers of the world only exist because cheap money is willing to have a go. And presumably, if cash interest rates weren’t so punitive, the willingness to ‘have a go’ would be less.

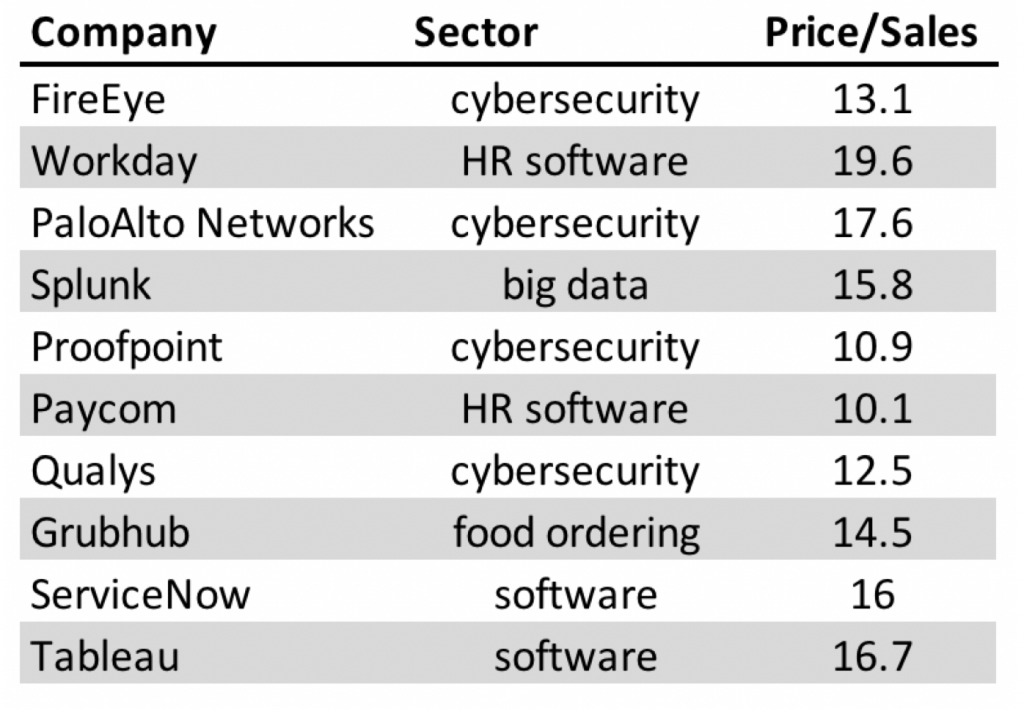

Table 1. A selection of US listed company Price-to-Sales ratios

As the American economist Herb Stein once wryly observed, if something cannot go on forever, it must stop. Table 1. Lists several tech companies along with their price to sales ratios. Be sure to read that price-to-SALES!

QE and QT

The positive outcome of quantitative easing (QE) has been that we avoided a depression. The negative outcome, aside from the fact that central banks are now addicted to QE as a conventional monetary policy tool, is that it has produced shortages, wasted resources and disincentives to save – consequences that almost all price controls produce. QE is another name given to controlling the most important price of all – the price of money; interest rates.

It’s probably too early to call but one of the consequences of QE has been a misallocation of resources. Corporate debt has soared, and equity misadventure has been hot on its heels. Most of the debt has been used for financial engineering such as share buy backs, special dividends and M&A. Meanwhile much of the equity capital has been directed toward fueling a profitless attempt at disrupting profitable incumbents.

Do you think if interest rates on term deposits were 10 per cent Uber could have raised $29 billion since 2009 to fund a phone App that would take ten years to try and displace taxi companies around the world without properly paying its workers, while avoiding any regulatory response and while remaining unprofitable?

In 2017 Airbnb reported a US$93 million profit on US$3.3 billion of revenue and a market valuation of US$30 billion. Closer to home, Woolworths has a similar market valuation to Airbnb of A$38 billion, but it reported a half year profit of A$969 million – almost ten times Airbnb’s full year profit.

Warren Buffett once said that its only when the tide goes out we will see who was swimming naked. When rates rise, or liquidity diminishes, it will be interesting to see how many corporate zombies are being kept alive by a steady flow of cheap and easy money from private equity, and share-market investors willing to support another funding round of a profitless idea, or another deferral of manufacturing targets.

Australia is not immune

There are several Aussie listed companies that rate a mention in the context of being expensive and marginally profitable or unprofitable. In Part 2 of this thought bubble, we’ll list some of them and explore the expectations that need to be met to justify their prices.

The Montgomery Funds own shares in Woolworths. This article was prepared 30 May 2018 with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade Woolworths you should seek financial advice.

What has fueled all of the rapid advancement we have most recently witnessed? The answer of course is abundant cheap money. Share on X

Come on Roger, get with the program. P/S is the new P/E!

Oh. Thanks for getting me back up to speed. I knew I was missing something Guy.

i just love how old sayings expose the simple reality of even complex issues like this one, and the Herb Stien one is a beauty, “if something cannot go on it must stop” and in the case of cheap money it’s the stopping part that worries me, and I don’t think people understand the enormity of the consequences of ending cheap money or even stopping the long term cost of money from trending lower, after all, it has only given very weak growth over the last decade at best and many would argue non at all.

I just wonder what the true lost opportunity cost has been as a result of a decade of governments forcing society to support many non productive companies (zombies) and an ever growing unproductive public sector. We have been basically digging holes and filling them back in to a large extent. A massive waste of resources, and on the very eve of the ageing demographic crisis that lies just ahead of us.

And I think it has been almost criminal how the likes of Uber and Amazon have been allowed to trash long term productive industries using their zero cost and zero profit business models . Just another perverse consequence of the free money if your big enough economy.

When all this stops it’s going to hurt. But as Paul Keating once said it’s the recession we have to have.

Nice one Andrew. Apologies for the delay in publishing.

Remember what happened with the too big to fail club. Now we have even bigger too big to fail as well as the too big to pay club, that is too big to pay – taxes due to no profits, interest on capital deployed due to free money, dividends because it’s only share price growth and p/s that matters ,and wages thanks to AI and robots.

Keeping in mind that these too big to pay companies have displaced many thousands of smaller companies that made profits, paid taxes,dividends,wages, and market-based interest on capital deployed as they had no access to free money.

Also we have a regulatory environment that very much favours the too big to pay club, of which Uber is a good example and Facebook, as authorities are only just now grappling with even how to regulate these new industries/companies without damaging smaller companies that have already been devestated by the too big to pay club