Six challenges facing the revival of Aussie manufacturing

After years of standing by as our manufacturing industries were sent offshore, the Federal Government has set up a task force to restore local manufacturing. “Australia drank the free-trade juice and decided that off-shoring was OK. Well, that era is gone,” Andrew Liveris, who is on the task force, told the AFR. It’s a great idea, but there are some mighty challenges ahead.

Liveris will be working with Ned Power’s advisory commission. He is the former CEO of the US Chemical giant Dow Chemical, and sees the current crisis as an opportunity to kick-start a resurgence in local manufacturing.

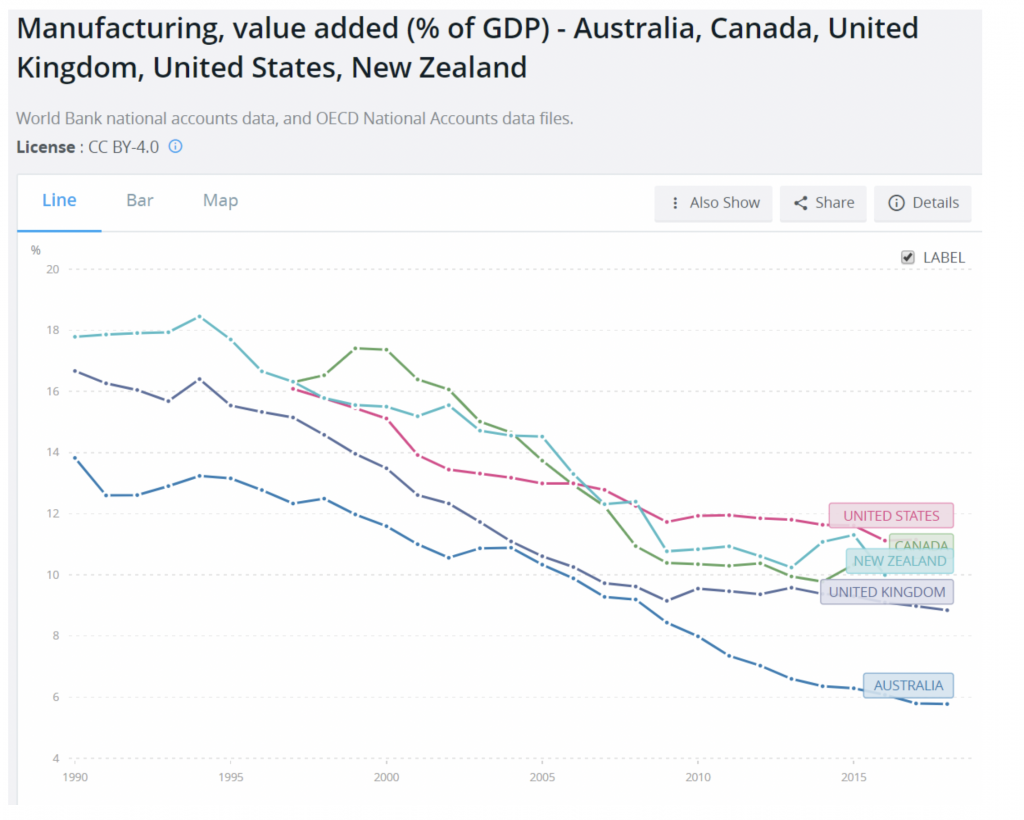

To start with, let’s have a look at the recent history of manufacturing in Australia. It should not come as a surprise that manufacturing as a per cent of total GDP is lower for Australia than for other comparable countries given our heavy focus on resources exports but it was a bit of a surprise to me to see the extent that we are lagging other comparable countries and also the extent the percentage has declined over the last 30 years.

If we look at this chart below which contains data from the World Bank, we can see two things that stand out:

- Manufacturing as a per cent of GDP in Australia is half of what it is in the United States. This is probably not that big of a surprise but what was surprising to me is that it is also roughly half of what it is in Canada and New Zealand, which are also countries with significant natural resources.

- It is also interesting to see that Australia is the country where the percentage has declined the most over the last 30 years, meaning that we have specialised in the extraction of natural resources and other non-manufacturing areas faster than other countries.

Source: World Bank and OECD

The current crisis has in many ways highlighted the issues with having little local manufacturing capacity. There are many, but to me the most important are:

- In times of a crisis of any sort, that impacts the free and efficient movement of goods across the world, having little local manufacturing capacity means that you can be disproportionally impacted by such disruptions as a higher percentage of the goods needed for the efficient functioning of the economy and even to fulfill basic human needs are imported and hence at risk when a crisis hits.

- Having little local manufacturing capacity and skills also means that you have low ability to focus your limited resources on the most critical needs when a crisis hits. As we happen to have local manufacturing of ventilators, this is probably not the best example, but it is interesting to see how the US has ordered its automakers and some other manufacturers to switch production and start making ventilators. Australia does not really have any industry that is capable of doing the same at scale as we do not have any suitable facilities and workers with the right skills to utilise.

- The more dependent a nation is on other nations for imports, the more vulnerable it becomes when there is a change in the geopolitical landscape surrounding the nation and, hence, puts you in a relatively weaker negotiating position if the priorities of other nations change for whatever reason.

Shifting macroeconomic settings to achieve an increase in local manufacturing will be a hard nut to crack as there are many vested interests that will potentially suffer from such changes. Six of the largest challenges that Andrew and the rest of the advisory commission will have to tackle are:

1. The Australian tax system needs to be recalibrated to capture more of any profits above a certain level generated by extraction of natural resources and then channeled into giving tax incentives for local manufacturing operations. This will probably have to be through some super-profit tax which has in the past proved very unpopular with the strong interests representing the resource industries.

2. The Australian university sector will have to refocus away from the mass education of foreign students which is debasing the overall level of education (Australia has by a factor of 2x the highest portion of foreign students in the world) to being focused on applied science performed in collaboration with industry. This most likely means that the government will have to start funding universities again with money targeted for specific purposes. This will mean more public oversight over these institutions which is something that they will likely resist strongly.

3. A new employer-employee labour framework. Australian labour productivity has not improved for around 10 years and for manufacturing to reemerge I suspect that the current EBA system needs to be focused much more on linking productivity to pay which will be a tough thing to get unions to come to grips with.

4. Tax changes that encourage investments into productive assets instead of into non-productive assets like residential real estate to lower house prices and rents to free up capital for a rebuilding of manufacturing companies. This will be strongly resisted by the real estate industry and domestic property investors.

5. Connected to the previous point is a framework that incentivises banks to lend to small businesses instead of to real estate. Australia’s banks are significantly under skilled in SME lending compared to the rest of the world and will need to rebuild this skill set urgently.

6. Lower energy prices by freeing up gas to be used domestically on the east coast instead of being exported to such an extent that Australian domestic gas prices are much higher than the price for the same gas received from being exported to Asia. This will be fiercely resisted by the energy companies.

As you can see from this list, there are quite a few pretty powerful interest groups that to my mind will need to come to grips with a new reality if the advisory commission will have any long-lasting impact.

Click here to read the AFR article – Liveris calls the start of the on-shoring era

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Australian Manufacturing industry adds the same value to GDP per capita than in France, NZ and Canada.

The Resources Industry is a giant that hides Manufacturing Industry in % of GDP. Using % of GDP to compare with other countries seems to be wrong.

Australia already have a massive Manufacturing Industry as value add to GDP per capita. (Value add to our quality of living)

Does it make sense to target the same level Germany or USA have? Can we do it without affecting other industries productivity? Not sure.

Roger’ MFG AUS article makes me subscribe w/him.

Missing are AUS dismall export logistics, I.P. items suitable to license offshore, under due-specific to foreign markets.

Took us 50 years and most Olympics since Munich 1972 to license manufacture in 10 countries.

Two years ago we decided to ‘repatriate’ our R&D to AUS.

Now buying advanced Dies & Machinry to get ready in Brisbane for post-Covid export commerce.

Anti Kajlich

Anti Wave Int’l PL

http://www.anti.to

Excellent article Andreas… it has been amazing to witness how quickly many of the inevitable trends that I have discussed at http://macroedgo.com have been accelerated under the conditions caused by the pandemic… it is refreshing in many ways to see high level thinkers be able to bring these issues to the fore and begin to think about how they can be enacted… that is where my optimism lies

Thanks Brett! Yes hopefully it does not descend into party politics but we can actually use this crisis in a constructive way.

Wester nations do not have free trade of free markets or honest money or freedom since 1914.

The folks who have brought us Nafta and presume to call it “free trade” are the same people who call government spending “investment,” taxes “contributions,” and raising taxes “deficit reduction.” Let us not forget that the Communists, too, used to call their system “freedom.”

The case for voluntary exchange has nothing to do with the question of the number of jobs that voluntary trade is supposed to create, or not create, or even destroy. The case for voluntary exchange is based on the case for economic liberty. It is based on the idea that two individuals who want to better their condition have a legal right to make an exchange that each of them believes will improve his situation.

Microeconomics: The study of who has the money and how I can get my hands on it.

Macroeconomics: The study of which government agency has the gun, and how we can get our hands on it.

Macroeconomics rests on a series of assumptions, none of which is ever discussed in a first-year textbook on economics.

primary assumption: two dozen individuals who have proven unable to make more than $60,000 a year in an unregulated free market possess the ability, when serving as members of a Congressional committee, to regulate a subsection of the economy that generates at least a hundred billion dollars a year.

secondary assumption, namely, that after a Congressional bill is signed into law, it will be enforced fairly and efficiently by salaried employees of one or more Federal agencies, which are ostensibly under the authority of the President, but whose employees are protected by Civil Service legislation and cannot be fired for any reason except malfeasance in office

The underlying premise of macroeconomics is that we can trust the abilities of Congressmen to pass legislation which tenured bureaucrats can and will administer fairly, coherently, and safely, so that the free market’s allocation principle of “high bid wins” cannot become the governing principle of economic distribution.

From now on, when you think “macroeconomics,” think, “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help you.”

thanks Ned

Still, I know under which regime I’d rather live.

Hi John,

That is probably a way to do it. Separate entities that the universities does not have control over is probably a good idea.

The universities are where much of the rot comes from.

“This most likely means that the government will have to start funding universities again with money targeted for specific purposes. This will mean more public oversight over these institutions which is something that they will likely resist strongly.”

I am not sure how to solve this problem but perhaps what needs to form is discrete institutes and colleges (like CSIRO) that sit separate from the universities insulated from their nonsense and where innovative, and pragmatic, research can be done and where profit motive is not the goal. ‘Money targeted for specific purposes’ might not be quite right – money allocated in strategic ways that would better serve the national interest would be a much better approach.