Should Australia cut the corporate tax rate?

Right now, there’s a debate raging about the need to cut corporate tax rates in Australia. As usual, some of the arguments are overly simplified, if not misleading. The questions are: would a tax cut deliver the benefits spruiked by the government, and who would benefit the most? Let’s take a look.

The government wants to lower the tax rate with the argument that it will stimulate investments by companies in Australia and lead to more jobs and higher wages etc. The opposition is opposed to these proposed cuts, and it seems like the Liberal Party’s coalition partner, the National Party, is not too keen either.

The whole debate was kicked off by the US tax cuts that came into effect at the beginning of the year which lowered the US statutory company tax rate from 35 per cent to 21 per cent along with a lot of other changes to the US tax code.

We have also seen some other countries lower their corporate tax rate recently (Japan and Germany for example)

Theoretically, a cut to the corporate tax rate should result in a higher portion of a company’s profits accumulating to the shareholders rather than to the government and hence it should in theory be positive for share prices.

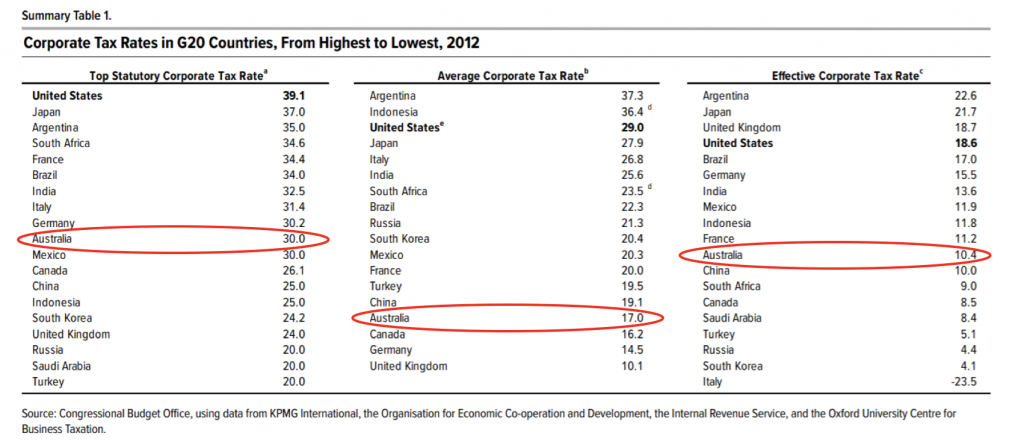

In light of this, I thought it would be interesting to have a look at a comparison of international tax rates. The Congressional Budget Office in the US has helpfully put a table together which I think is interesting as it shows not only the statutory tax rate but also the average (what companies actually pay taking into account deductions and foreign income etc) and the effective tax rate (the tax rate on an investment that is just about breaking even, i.e. the tax rate you would pay on you first dollar of profits).

The table is from 2012 so a little bit out of date but generally correct with the major difference that Japan has lowered its tax rate to ~30 per cent from the 37 per cent shown in the table and, as discussed above, the US has lowered its tax rate substantially.

There are a few interesting things to note from this table:

- The range in statutory tax rates is wider than in average and effective tax rates. This is due to the fact that a high statutory tax rate generally means that there are more generous deductions or other ways for companies to lower their tax rate.

- Although Australia is in the middle of the range when it comes to statutory tax rate, it is towards the bottom when it comes to the average tax rate. There are a few reasons, such as:

- Australia has historically had a quite generous interpretation of transfer pricing legislation enabling companies to transfer profits to lower tax jurisdictions.

- Australia has relatively generous R&D concessions enabling companies to get tax credits for money spent on R&D. Australia and New Zealand are the only countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- (OECD) with dividend imputation. In other countries, companies pay tax on their profits and then investors pay tax on the dividends they receive, but in Australia and New Zealand, companies get franking credits for tax they pay and can pass these on to domestic shareholders.

Now, we are not making a judgement on the merits of a corporate tax cut but given the above, we have a few comments:

- From a competitiveness standpoint, we struggle with the argument that Australia must cut its corporate tax rate to stay competitive given that it is already towards the bottom end of the range in terms of the average tax rate.

- We also struggle a bit to see how a cut to the tax rate will stimulate investments. Corporate interest rates are at all-time lows and many companies we look at have indeed got quite lazy balance sheets that could be utilised more aggressively if the investment opportunities were there.

- The fact that Australia has a dividend imputation system means that Australian shareholders will not benefit from a corporate tax cut as the amount of franking credits will decrease if a company pays less tax. A cut in the corporate tax rate will therefore primarily benefit foreign shareholders of Australian companies. (And yes, as an Australian domiciled fund, we are talking our own book here).

Now, please note that we are not averse to a corporate tax rate cut but just wanted to point out that some of the arguments used in the political debate are quite overly simplified and should be taken with a grain of salt.

Right now, there’s a debate raging about the need to cut corporate tax rates in Australia. The questions are: would a tax cut deliver the benefits spruiked by the government, and who would benefit the most? Share on XThis post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Why assume that a corporate tax reduction will lead to more Dividends!!!

I should imagine growth companies will retain a good portion of the tax cut for reinvestment purposes which, in turn, will lead to a higher intrinsic value.

PeterB

Hi Peter,

It is correct that some companies will retain a portion and reinvest. It is though not a given that this will result in profitable (key word!) higher growth rates, only if they were capital constrained before and the additional capital available is reinvested at a marginal RoE that is higher than their cost of equity is the higher growth rate value adding.

We look at a lot of companies and it is very seldom that we see (at least larger) companies being capital constrained to the point that they are not investing. Debt funding is generally readily available and attractively priced for “good” companies.

Hi Andreas,

The purpose of dividend imputation is not to provide franking credits for shareholders – it’s to avoid double taxation of profits. A corporate tax cut does not detract from this principle. That fact that foreigners may benefit from a corporate tax cuts seems fair enough if the tax cut leads to more foreign capital investment (a main objective of a corporate tax cut), more jobs and more profit – and more dividends for all share holders (including Aussies).

Hi Andreas, I think it’s really the SME that deserves and needs a further tax cut along with meaningful relief of over bearing regulation. I know that most of the tax deductions you have listed above, r and d , off shoring profits etc are largely irrelevant to SME’s but probably very effective for large companies. Another major problem for SME’s is access to capital, while SME’s are starved of capital, large companies issue bonds and can raise capital easily even if they make no profit. My bank recently advised me to borrow money from them as a wage earner instead of through my company because it would be easier to approve, yet my wage is totally relient on the performance of my company, Banks hate business, unless it’s big business. And this situation has led to very low small business creation numbers which has been in down trend for many years, we are effectively choking innovation off before it even starts, while at the same time keeping large zombie companies on life support when it’s the exact opposite of what needs to be done.

Have you seen those photos of the original Microsoft team in the early 80s ? a small group of hippies at university without a cent between them, the point is that big businesses come from small ones, they need to be nurtured not choked.

Hi Andrew,

Fully agree that supporting SMEs are very important for the long term development of an economy.

Your point of access to capital is very relevant and in part caused by capital charges. Basically banks have to set aside certain amount of capital for every loan they make. The less capital they have to set aside, the higher the return on capital for the banks.

The risk weighting for SMEs are much higher than for mortgages and for large businesses. SMEs are by their nature riskier than other loans (less assets that can be put up as security, generally only one income stream vs. multiple income streams for large businesses etc.) so the risk weightings should be higher than for other loans but there is an argument to be made that the risk weightings have historically been incorrect. It is indeed probably one of the main reason we have such a property bubble in Australia currently, the banks have shifted their lending books from a weighting of ~30% mortgages 25 years ago to around 60-70% currently. This is a lot of money that has moved away from financing productive businesses to financing inflated property prices which is non-productive.

Yes I think the risk weightings are way out of wack, as it was not SME’s debt that nearly destroyed the global economy in the financial crisis of 2008 and forced governments to bailout many large companies with tax payers dollars and subsequently print trillions of dollars to just to keep the global economy treading water, all a direct result of trying to replace a production based economy with casino style one.

Agree entirely with your sentiments Andrew. I think the ideology that says tax cuts for big business leads to job growth needs serious reappraising too.

That NAB simultaneously announces a record profit AND a cut to 6000 jobs speaks volumes about the blindly-accepted assumption of the trickle down effect.

Additionally, automation will be more quickly adopted by large companies because it will initially be expensive. Automation will lead to a hollowing out of jobs.

Yes it constantly amazes me how nothing ever changes, when the problem is so glaringly obvious. Trickle down is really trickle up, and this can be easily seen in any graph you want to google on weath disparity, it’s almost exactly and inversely proportional to the cost of debt and the volume of money creation, and why is this so? Again very obvious, this low cost debt is only available to those who already hold assets, yes the rich ! And what happens to asset prices as a result of this? They inflate, and what is the result of that? The rich can now borrow more cheap money against these now higher valued assets to further inflate asset prices and a long term positive feedback loop is created, that entirely excludes the average family. This phenomenon has been in place for decades and relies totally on the ever decreasing cost of debt and increasing supply of money to sustain the model.

The question is what happens when the cost of debt approaches zero, do assets rise to infinity? obviously not, but we are going to find out.

It’s like one of those really obvious jokes you hear, where The attempt at humour is such a failure they make you laugh loud. But I don’t think the ultimate outcome of this experiment will be very funny.