Is the extraordinary bond market rally about to end?

The 36-year bond bull market is stretched and set for a serious nose dive, says Harvard University researcher, Paul Schmelzing. Schmelzing says global inflation could trigger large losses on bond holdings, subpar growth in developed markets, and balance sheet risks for banks.

Schmelzing, from Harvard’s History Department and an academic visitor to the Bank of England, released his paper during our summer break. It analysed the bond market through the lens of nearly 800 years of economic history.

You can access the paper here. Here’s an excerpt.

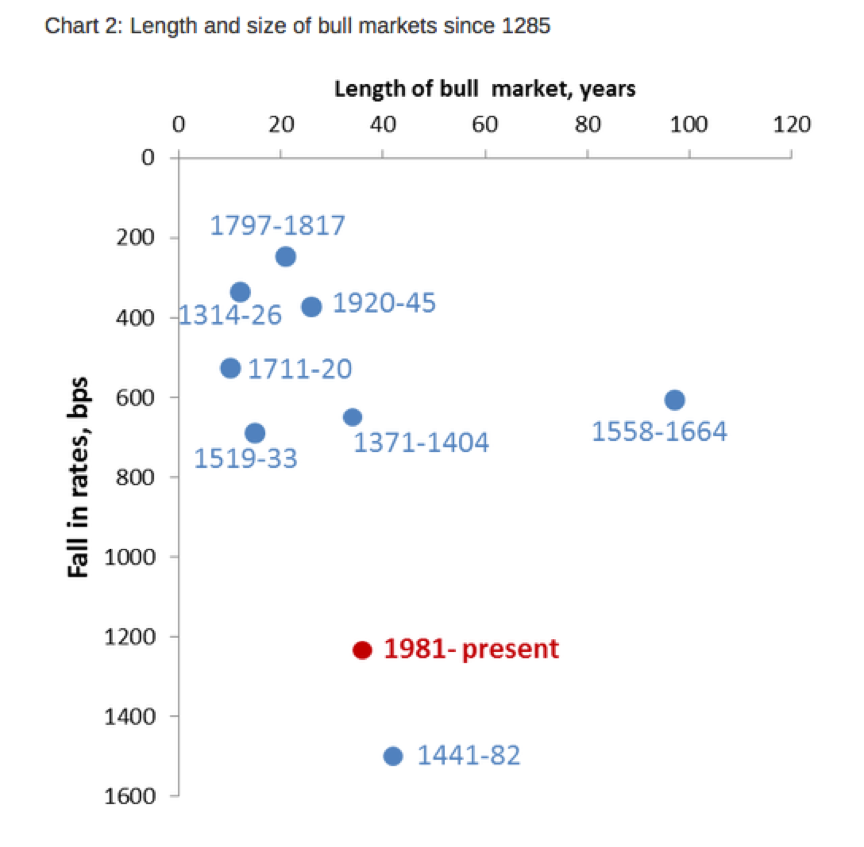

“Judging purely by historical precent, at 36 years, the current bond bull market had been stretched. As chart 2 shows, over 800 years only two previous episodes – the rally at the height of the Venetian commercial dominance in the 15th century (1441-1482), and the century following the Peace of Cateau-Cambresis in 1559 (1558-1664) – recorded longer continued risk-free rate compressions. The same is true if we measure the period of average decline in yields per annum, from peak to trough. With 33bps (0.33 per cent), only the rallies following the War of Spanish Succession (1711-1720), and the election of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor (1519-33) surpass the bond performance since Paul Volcker’s “war on inflation” (1980).”

Twelve Modern US Bond Shocks (since 1925)

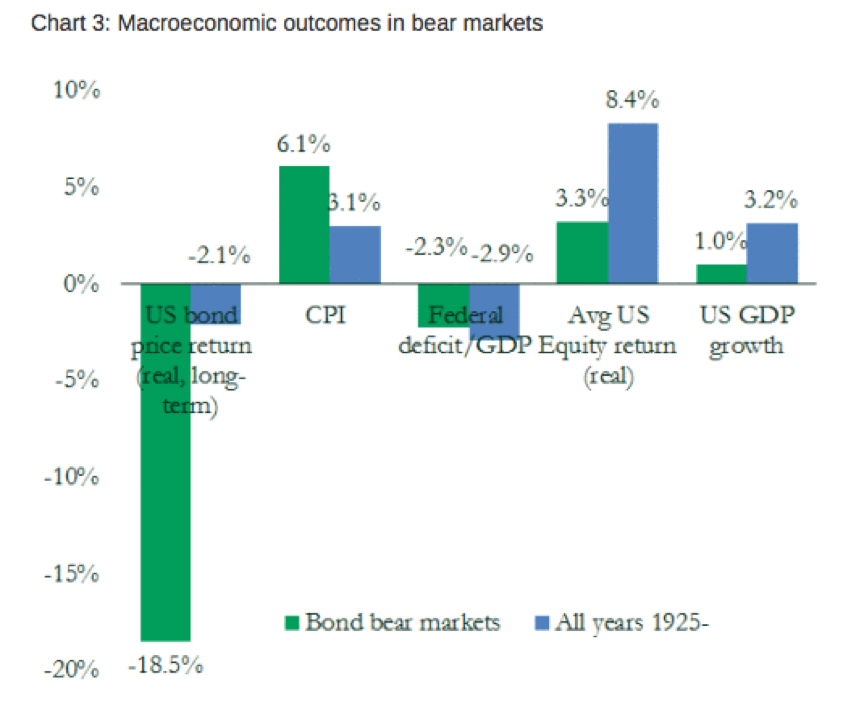

Paul claims there have been twelve modern US “bond shock” years (since 1925), “during which selloff dynamics cost long-term sovereign bond creditors more than 15% in real terms.” Some pertinent points are worth considering:

- While historically inflation acceleration has been a solid predictor of sharp bond selloffs (an average of 18.5 per cent, in real terms) – some prominent episodes (1994) appear less correlated with fundamentals, and can inflict similar levels of losses; and

- An increase in the supply of bonds seems not decisive to the weakening in price levels (rising yields).

And Paul concludes with the following:

- “Global inflation dynamics are picking up, at a time when Central bankers voice more tolerance for “inflation overshoots”; and

- “By historical standards, this implies sustained double-digit losses on bond holdings, subpar growth in developed markets, and balance sheet risks for banking systems with a large home bias” (with a focus on Japan and Italy).

It is worth noting that over the six months to December 2016, US ten-year bond yields increased from a low of 1.36 per cent to a high of 2.70 per cent, and this compares with the current 2.45 per cent.