How many stocks should you have in your portfolio?

Today we are going to keep this post as simple as possible and focus on three key elements that we consider important (but by no means exhaustive) when identifying investments and managing a portfolio. For simplicity we have broken down these categories into quality, quantity and return considerations which we hope may add some value to your investing endeavours.

Quality often means different things to different investors. For example it could refer to a business’s balance sheet, its prospects, or its assets. For us however, quality refers to a company’s ability to earn high returns on invested capital for a sustained period of time.

At Montgomery we’d much rather own a handful of businesses that can reinvest meaningful amounts of capital back into the business at 20 per cent per annum, than 100 hundred business generating 5 per cent and paying almost all of its earnings out as a dividend. Something we touched on recently here.

We believe that if you can identify a business that has an extended competitive advantage period and is able to generate high returns on every dollar it reinvests, it’s highly likely that you have an investment asset that will; 1) Have attractive growth prospects over the medium term and, 2) Will perform solidly over the long term. It is for these reasons that you should seek to build a portfolio filled with these types of businesses, purchased and owned at attractive prices.

Quantity. Again, this will differ depending on who you ask, but just how many businesses should you aim to hold in your portfolio?

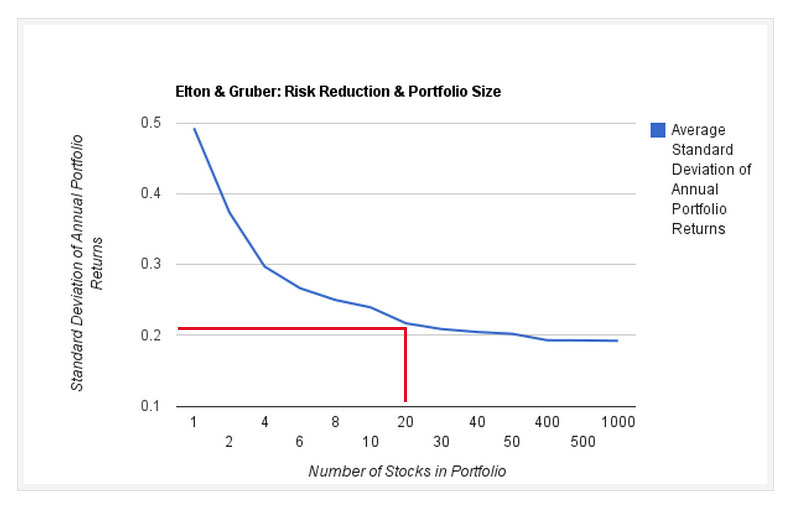

It’s a well-known fact in academic research that the majority of benefits from diversification (spreading risk) accrue in a portfolio comprised of just 10 businesses with risk reduced to an even lower acceptable level when a portfolio reaches 20 positions.

In “Risk Reduction and Portfolio Diversification: An Analytical Solution” (Journal of Business, written way back in 1977), Edwin Elton and Martin Gruber found that the benefits of diversification are negligible once a portfolio increases in size beyond 20 different investments. To demonstrate this graphically, the chart below plots portfolio standard deviation (the academics measure of risk) against the number of holdings.

In our view this makes logical sense. In practice, one only needs to consider the basics of investing and ask the question; are you adding value by putting money into your 30th ‘best idea’? We believe the answer to that question is relatively straightforward, preferring to add more to our highest conviction ideas and concentrating rather than diversifying broadly.

So when it comes to building your own portfolio, think about how you could be backing your best ideas more meaningfully rather than adding more and more hopefuls which will only see you building a library of investments. We’ve seen many such examples of just this over the years, portfolios which come with the frustration of failing to deliver the outcomes desired in terms of returns.

And finally, when considering returns, whilst many investors I regularly speak to are constantly trying to pick the next winner, we believe that avoiding the losers and making dumb mistakes in the share market is just as important.

There’s a simple mathematic equation that’s worth considering before ever buying a share on the stock market: if you lose 50 per cent of your capital, you have to then generate 100 per cent back just to break even. Burn this one into your brain.

If you have $10,000 invested in a company and you buy it on nothing more than a tip and it halves in price, which constitutes a paper loss of $5,000 or 50 per cent in the red. From that position the share price either has to double just for you to get back to where you started or your next tip better be a good one!

It’s a situation which can put you at a significant disadvantage even if you only have one poor performer in your portfolio, which is why as part of the research we undertake and indeed well before we ever push the buy button, instead of asking how much we can make, first we ask how much can we lose.

If we are considering an investment that can make us a little but has significant downside risk, then the investment idea probably doesn’t stack up and the risk to reward ratio is just not in our favour.

Rather, we attempt to fill our portfolio where this situation is reversed. That is, where in our view the downside is limited, but we have reason to believe there is materially more to the upside.

In that way you tilt the risk to reward ratio in your favour and hopefully, the returns.

Russell Muldoon is the Portfolio Manager of The Montgomery [Private] Fund. To invest with Montgomery, find out more.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

david klumpp

:

Hello Roger: I think back to your excellent Webinar series on the topic of portfolio construction (about 6 mths ago on Skaffold) as a very helpful contribution to this topic. In that you highlighted a need to limit one’s exposure to any particular stock, and a rough guideline was an initial investment of 3-7% of funds. Then if, as Edith points out, a stock rises (to say 10-20% of portfolio value) then you need re-balance that portfolio back towards your limit. So, this is another factor to keep in mind: portfolio exposure to any one stock. For that reason I tend to hold 15-20 stocks, because it means I will have around only 5-7% (10% max) exposure to any one stock. Thus it fits with Russell’s point of reducing variability (achieved at 10 stocks), and also keeping potential losses in any one stock to an acceptable minimum.

Patrick Poke

:

For a non-professional investor like myself it’s also important to limit the number of holdings purely for practical reasons. I don’t have time between full time work and study to monitor 30 or 40 different holdings properly, if I were to hold that many there is no way I could read the interim and annual reports fully after each reporting period (even if I could, it’d take too long to get through and therefore too long to react). I find 10-15 is the right number for me personally, it allows me to do the level of research I feel is required, focus my efforts, but still achieve a reasonable level of diversification.

Roger Montgomery

:

You might find this useful patrick: https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/premba/finance/s6/s6_5.cfm

Roger Montgomery

:

Patrick, this is useful for your thinking. See the chart under section III here: http://viking.som.yale.edu/will/finman540/classnotes/class2.html

Patrick Poke

:

Thanks Roger, will have a read of both of these over the weekend.

Edith Wake

:

I agree with the idea of adding more to our “highest conviction ideas”. However what if your “highest conviction ideas” in your portfolio have increased well beyond their intrinsic value and you want to make some additional investments?

It’s difficult!!

Roger Montgomery

:

That is indeed a challenge Edith. Sometimes a relative valuation approach can help with that decision but you have to decide whether it suits you. In the long run being invested generally works so the relative approach is worth investigating.

Greg McLennan

:

Hi Russ,

I don’t think too may people can argue with that. However, I reckon that many follow that with a “but” and an excuse to buy something else as well which then takes them a long way from what you are talking about.

“But BHP has a suite of quality assets”

“But CBA has a good yield”

“But XYZ is on a PE of 9 compared to ABC at 16”

Roger Montgomery

:

Good point Greg.