Don’t bet on a U.S. recession in 2023

After a 4.65 per cent increase in interest rates this past year, why isn’t the U.S. economy tanking? And why aren’t retail sales plummeting? One reason, perhaps, is that during the pandemic, many home buyers locked in fixed-rate 30-year mortgages at ultra-low rates, and they are thus unaffected by recent rate rises. If I’m right, the U.S. economy might avoid a recession in 2023.

Despite various predictions that central banks would trigger a recession by raising rates to quell inflation, economic growth, particularly in the U.S., has endured. The strength of the U.S. labour market and reasonably robust consumption, despite the Fed Funds rate rising from 0.1 per cent to 4.75 per cent in a year, has surprised economists and commentators and inspired the ‘no landing’ scenario – another version of the ‘Goldilocks’ economy.

As an investor, it’s one thing to agree with an observation, but it’s entirely another to know why the observation is occurring. Importantly, an explanation may help to determine whether the conditions are cyclical or structural, for example.

I have been digging around to try and understand why the U.S. economy isn’t collapsing in a screaming heap of recession despite a 4.75 per cent increase in interest rates, and I think I may have a reasonable explanation.

Mortgage interest rates declined so much during the pandemic that home buyers could purchase a house three times more expensive than before the GFC in 2007, and pay only a few hundred dollars a month more on their fixed rate 30-year mortgage than a purchaser in 2007.

Home buyers – the homeownership rate in the U.S. is approximately 66 per cent – could lock in historically low fixed debt costs on their biggest asset.

According to some estimates, a quarter of U.S. mortgagees are enjoying rates of three per cent or less. Two-thirds are estimated to be enjoying rates of less than four per cent.

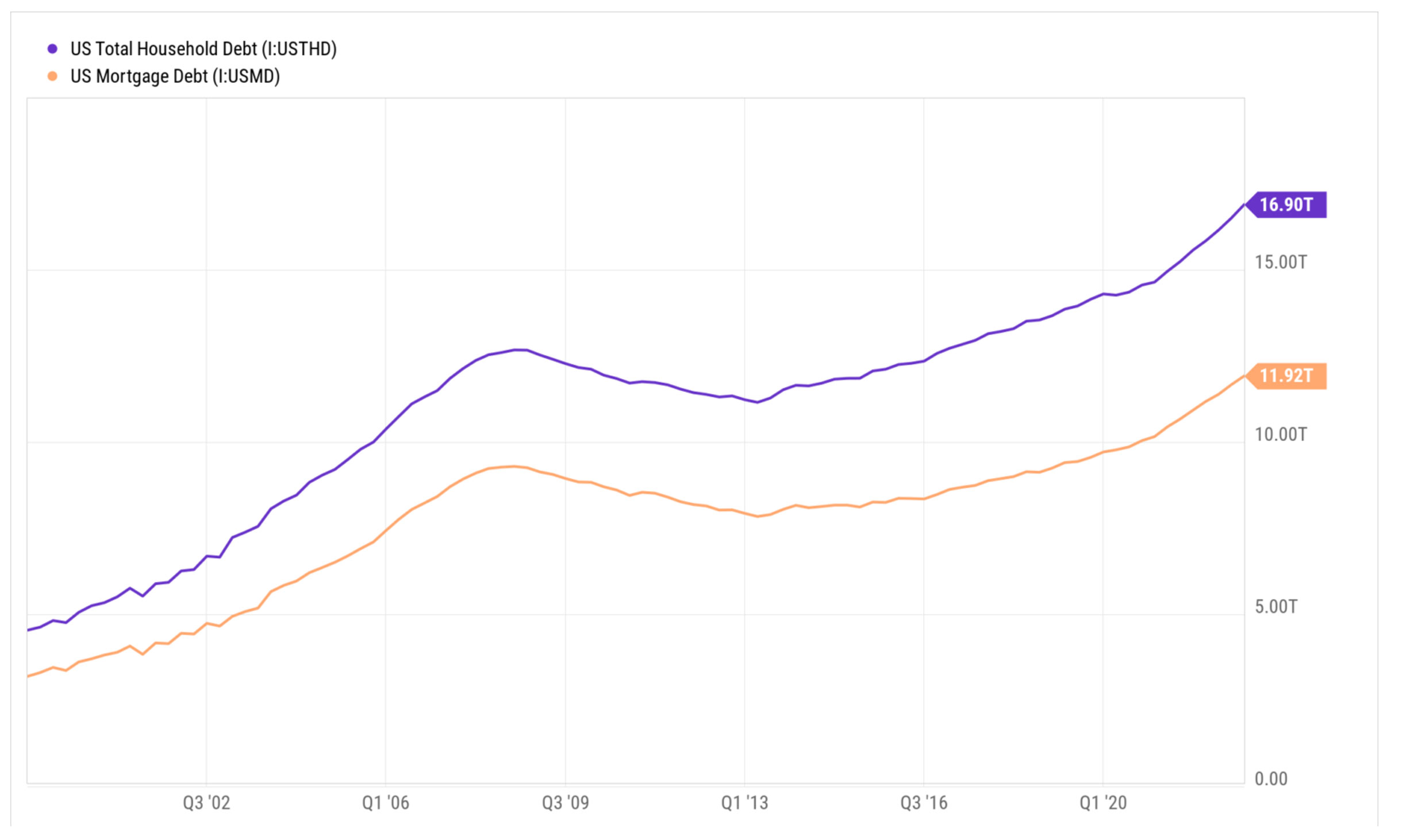

Figure 1. U.S. Household and mortgage debt

Source: YCharts, Ben Carlson

As Figure 1. reveals, at the end of 2022, household debt totalled US$17 trillion, with 70.5 per cent of that, or US$12 trillion, being mortgage debt.

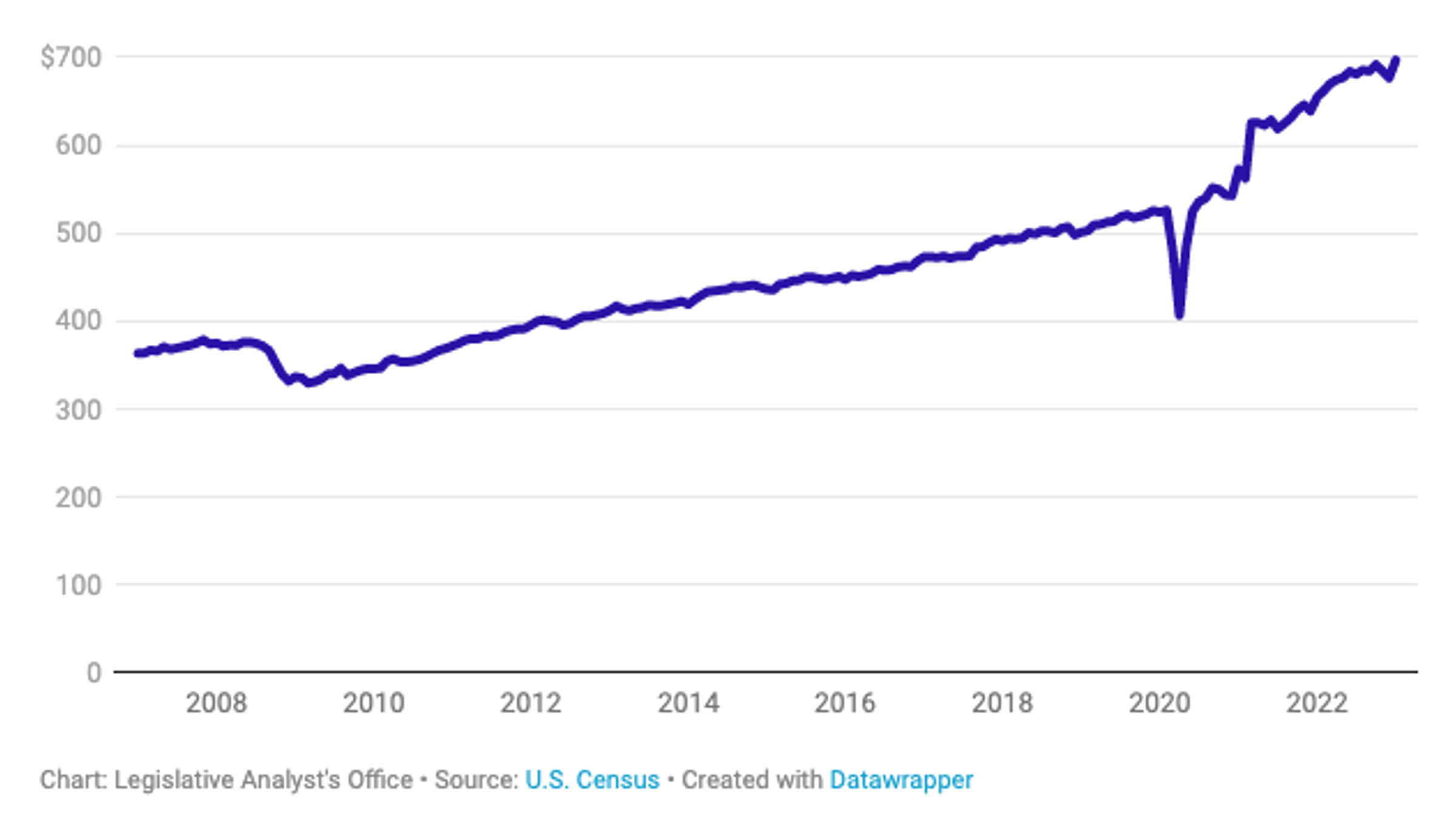

Figure 2. U.S. Retail Sales – millions of dollars per month (seasonally-adjusted)

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, retail sales appear to have grown rapidly between December 2022 and January 2023. Seasonally adjusted U.S. retail sales increased by three per cent from December to January. And perhaps even more impressively, cumulative twelve-month growth in retail sales from January 2022 to January 2023 was 6.4 per cent.

As an aside, retail sales declined by an unusually large amount between October and December. For three consecutive years, retail sales have reportedly weakened in November or December, with very strong growth in January following.

The consistent pattern suggests that the Census Bureau’s seasonal adjustment for monthly retail sales might not be working as intended. Investors should therefore probably turn to longer run comparisons that are less sensitive to seasonality, such as annual growth rates.

Across all goods and services purchased by consumers, U.S. prices increased, from January 2022 to January 2023, by 6.4 per cent. This roughly offsets the 6.4 per cent growth in sales over that twelve-month period. Therefore, after adjusting for inflation U.S. retail sales were flat over the 12 months to January 2023.

But that’s still not a decline, despite massive increases in interest rates designed to reduce consumer demand. And trend retail sales remain well above the pre-COVID trend. Despite the end of COVID stimulus measures, including ‘helicopter money’ and unemployment assistance to consumers furloughed during the early part of the pandemic, retail sales remain robust.

Could it be that the many millions of Americans who locked in ultra-low rates on their mortgages for new purchases, and when refinancing existing mortgages, are feeling a little less pessimistic, indeed perhaps, a little ‘confident’ now that rates have surged?

The tight labour market – most people outside of the IT layoffs have a secure job – and the locking-in of ultra-low mortgage rates for up to 30 years means many millions of Americans may be more liquid than economists predict. According to the U.S. Economic Policy Institute, the year-on-year change in private-sector nominal average hourly earnings for production/non-supervisory workers is 5.1 per cent. Meanwhile, even though house prices have softened recently, they remain well up on pre-pandemic levels.

If this is structural, the ‘no-landing’/Goldilocks scenario could confound those expecting a recession this year.

Two questions.

1. Even though existing US homeowners are sheltered, new home sales and construction should be tanking. Why aren’t a bunch of carpenters, subbies, labourers and junior real estate agents becoming unemployed?

2. The same basic patterns apply here even with our variable rate mortgage regime, surely?

I find current conditions a mystery as you clearly do too, and have no firm opinion on why, but I suspect Friedman’s “long and variable lag” thing applies. Just a bit longer and more variable this time around! You can make a kinda plausible story out of post-covid savings buffers and a labour-hoarding attitude of employers.

1. There’s a long pipeline of work, so yes, there’s a lag. If the local rental crisis, which is leading to rising rents and stiff competition by tenants, leads to a medium density development supply response, you might find it’s ‘off to the races’ again for carpenters, subbies, labourers and junior real estate agents.