A two-part framework for investing for growth

There’s a lot going on in the world right now with sufficient power to dramatically improve or destroy investment returns. Inflation, recession, a credit crunch, diminishing Central Bank liquidity and escalating geopolitical tensions all have the potential to alter sentiment in a second and change the fortunes for many.

And of course, as investors raise their gaze from the idiosyncratic factors of a company and its value, to the macroeconomic and geopolitical, confidence must necessarily decline. At best, what the U.S., the Federal Reserve, China or Russia does next is a guess.

And yet despite the landmines, investors must, by necessity, invest to maintain and grow their purchasing power. Without growth, purchasing power goes backwards. Whatever bottle of wine you can afford today, you won’t be able to afford it in a decade, without maintaining purchasing power. And for a couple retiring today, life expectancy statistics suggest they will need to fund the spending, for at least one of them, for 30 years. That means investing for growth.

It’s a difficult path to navigate but one must proceed, cautiously or otherwise. I offer here an elegant, two-part, framework for doing so.

Building the framework:

Question 1. What is the appropriate risk attitude/posture/positioning for you, or in the case of an adviser, for your client?

Remembering the indisputable need to maintain or grow purchasing power, every investor will have a different tolerance for risk. An adviser will likely take account of the following when formulating a risk profile for their client and establishing a base portfolio:

- Their resources or liquidity (their wealth)

- Their needs (how adequately can their wealth meet their needs)

- Age

- Income lifecycle: Are they still generating income to add to their wealth? Is the income greater than the outflows

- Desires, dreams and ambitions

- What is the tolerance to a 50 per cent decline (volatility).

From the answers to those questions, and with the history of volatility and returns for a variety of asset classes in mind, an investor, or their adviser, can establish the base portfolio weights and position the portfolio at the appropriate juncture on the continuum between defensive and aggressive.

Question 2. Will you maintain the portfolio’s initial position on the continuum at all times, allow it to drift but rebalance at regular intervals, or finally will you allow it to diverge based on what is happening in markets from time to time?

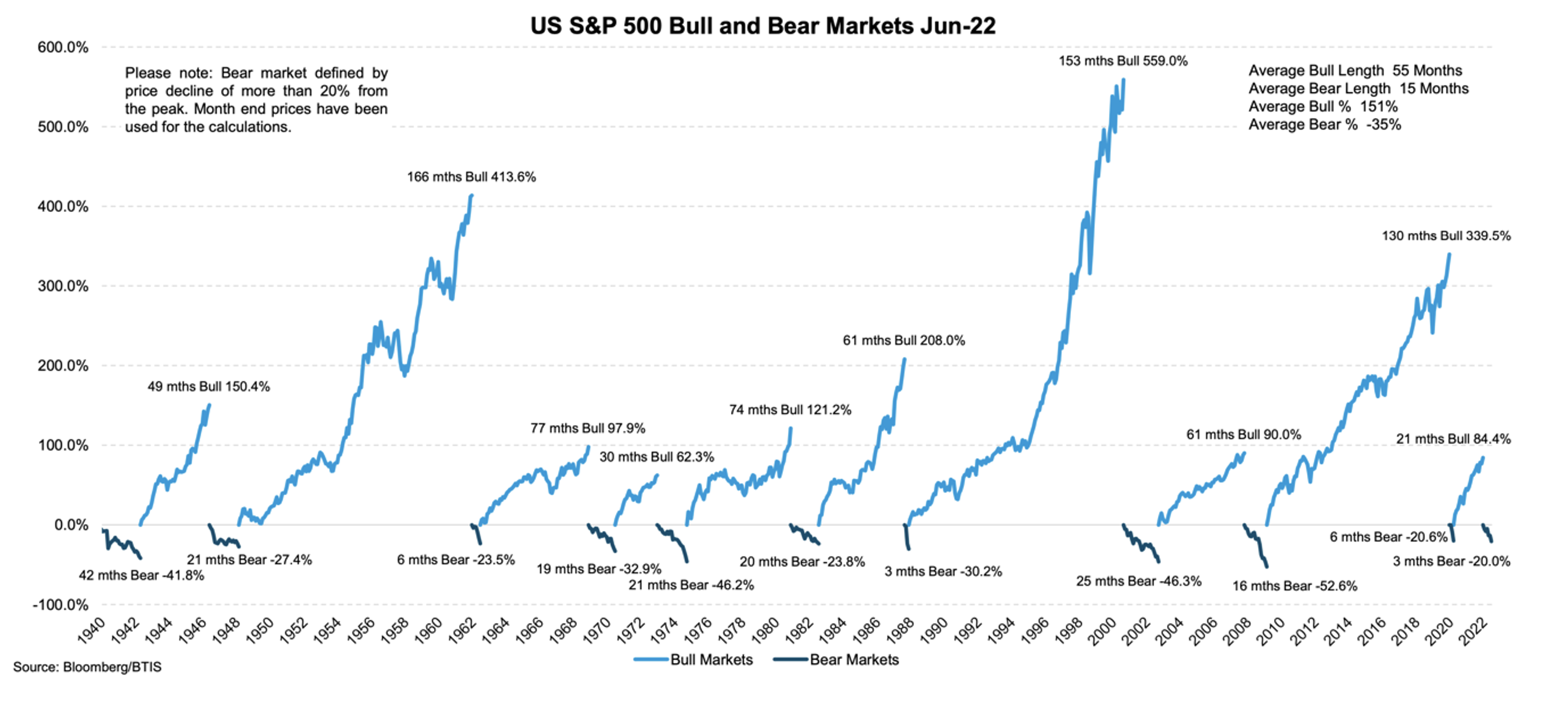

For most investors, particularly those who conclude they can’t time markets accurately or confidently, the best approach is probably to allow elements of the portfolio to move with markets (if investments have been selected with quality and growth in mind, over time they should increase in price. See Figure 1.) and rebalance back to the original weights regularly, for example quarterly or annually.

Such an approach forces the investor to reduce the weight of a component that has outperformed and add to components that have relatively underperformed – buying low and selling high (relatively).

Figure 1. Bull Markets versus Bear Markets through history

Of course, there will be times that all assets fall synchronously, in which case changes to relative weights will still be adjusted, adding to those that have fallen relatively more, and reducing those that have fared relatively well. Remember, if quality investments have been selected at the outset, either directly, or indirectly through a fund manager, the process of regular rebalancing will produce satisfactory results over the long run. The process also forces the investor to maintain exposure to markets that can reverse from sell-offs very quickly.

Some investors however will prefer, and for even fewer it will be appropriate, to adjust the portfolio constituent’s weights based on what is going on in the world, in currencies and in markets. At times these investors will adopt a more aggressive posture and at other times, more defensive.

Today, the combination of a withdrawal of stimulus by central banks, the tightening of interest rates, a stickiness to inflation, the possibility of recession and rising geopolitical turmoil over Taiwan, might reasonably be considered reasons to adopt a more defensive posture.

The cost is high

As Figure 1. reveals, there is a very high cost associated with selling growth assets, especially those that have been originally selected for their quality and long duration growth. While sometimes violent and unsettling, bear markets tend to be brief relative to bull markets.

The investor who moves to a more defensive position, by selling quality assets, will need to buy them back at some stage. Two smart decisions are required and timing both correctly is difficult and best left to those who might have proven they are prescient beings.

For everyone else, the framework suggested above is an elegant solution to navigating the inevitable vicissitudes of the market and modern finance’s impact on the world.