A crash is coming!

That’s a headline designed to capture your attention. If it has done so, it is highly probable that a crash is one of your fears. And for some people with that fear, the concern is great enough that it has impacted their investing outcomes and returns. For example, they may have held off buying shares in a company that subsequently rocketed higher, simply because you feared the market was due for a correction or crash. You may have also sold a stock too early, even though nothing about the company in which you owned the shares had changed. You simply thought some exogenous event would trigger a broad market correction. And, in a more extreme example, you were right in your prediction about the market falling, but the shares you owned continued to climb.

Feeding the above fear is a coterie of commentators predicting wealth-destroying cataclysms and generating revenue by selling their predictions to those who fear the same.

Back in the mid-nineteen nineties, when I was in my mid-twenties, I was working at Ord Minnett. I stumbled upon a newsletter (back then, it was a physical newsletter sent in the mail) penned by the practitioner of an arcane stream of technical analysis called the Elliot Wave Principle. The S&P 500 had just risen above 1000 points for the first time, and the Dow Jones had reached 8500 points.

I recall the newsletter said the market had reached the fifth wave, of the fifth wave, of the fifth wave. A ‘fifth of a fifth of a fifth’ was then interpreted as meaning the market had reached its climax and would suffer the ignominy of crashing and perhaps never surmounting the aforementioned ‘heady peaks’ ever again.

But then, in 1995, the Dow Jones rose 33.6 per cent. And then, in 1996, it rose 26.3 per cent; in 1997, 22.4 per cent; in 1998, 16.1 per cent; and in 1999, 25.2 per cent. Today, the Dow Jones sits at 42,063.36.

Shortly after reading the newsletter, I concluded that if the world’s Elliott Wave’s most senior practitioner could be so led astray by the wave principle, there must be something unknowable about it.

It was clear investment success lay elsewhere.

The sad thing is the lesson I learned 30 years ago is destined to be expensively relearned by many generations of investors who will come after me. Nothing is more frustrating than seeing a generation of twenty-somethings today following the practitioners of voodoo and astrology, now on TikTok and Insta, in their search for investment success and re-losing the same amounts of money.

Nevertheless, profiting from a crash, like the search for the Ark of the Covenant, remains one of the holy grails of investing.

So, what is the secret to profiting from a crash? As the above example illustrates, boldly predicting a crash and charging people for the insight is certainly one path. This method was reportedly pioneered in the 1920s by Roger Babson – the man often cited as the investor of economic forecasting – whose predictions about the stock market were based on Newtonian physics.

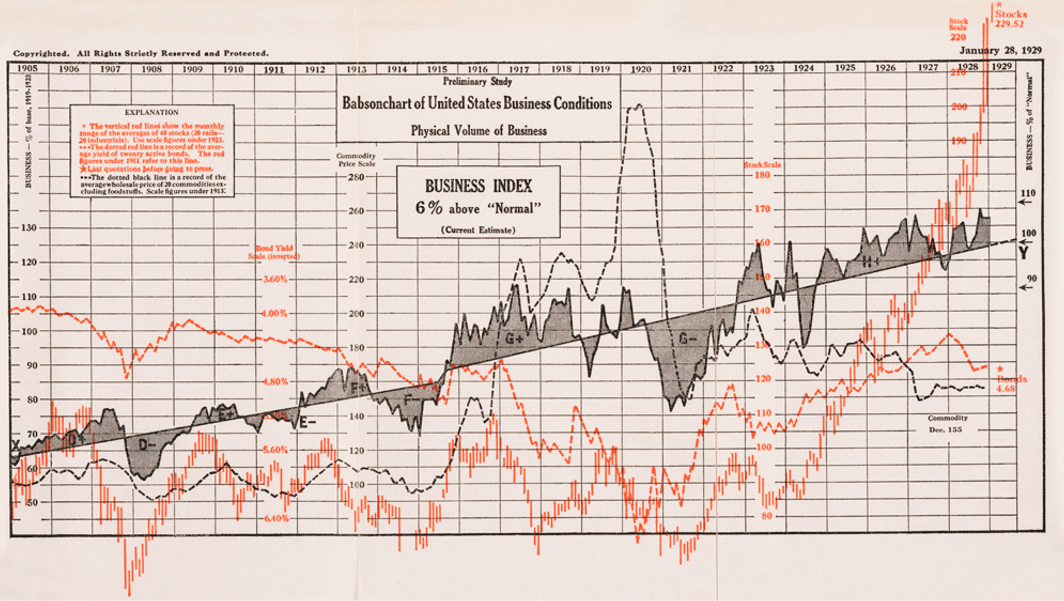

Figure 1. Babson chart of U.S. business conditions Jn.28, 1929

At the urging of no other than Thomas Edison, Babson created the Gravity Research Foundation, and it was at one of Babson’s seminars some years later that he illustrated how Newton’s Third Law (of action and reaction) could be applied to the stock market.

At the urging of no other than Thomas Edison, Babson created the Gravity Research Foundation, and it was at one of Babson’s seminars some years later that he illustrated how Newton’s Third Law (of action and reaction) could be applied to the stock market.

According to the New York Times, in September 1929, Babson warned investors that the stock market was about to collapse, suggesting they pay off their margin loans and refrain from taking on any new margin debt.

According to the New York Times, his argument was that only 40 of the 1,200 stocks then on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) had enjoyed a 42 per cent rise in the previous year, while half of the remaining stocks had dropped since the beginning of 1929. In other words, market breadth was limited, and the gains were concentrated among a few stocks. Sound familiar?

A month later, stocks plunged 12 per cent, and by 1932, stocks had declined 89 per cent and Babson was eventually blamed by some for causing the Great Depression.

Calling a market crash correctly, just once, can be enough to set a forecasting newsletter business up for life. Indeed, there is now a Babson College at which a monument stands at the site where Babson made his most famous prediction on 5 September 1929.

What is less known about Roger Babson is that he had made several incorrect earlier predictions about a crash for which he was derided, especially by Barron’s.

So, it’s important to remember what Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger – two of the world’s most successful investors – once wryly noted about forecasting the stock market: that the only way to be successful in the business of predicting, is to predict often. Because, as Danish physicist Niels Bohr once shrewdly observed, ‘it is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.’

In a 1919 Wall Street Journal article, author Spencer Jakob wrote; “Elaine Garzarelli, who nailed the 1987 crash in a TV interview, became the best-paid strategist on Wall Street and still profits from that call despite a spotty record overall. Her newsletter will set you back $495 annually…”

“Robert Prechter, who claims he predicted the 1982 bull market using an arcane “wave” theory and has since reaped millions of dollars from subscribers, has made several shocking predictions over the years, such as the Dow falling to between 1,000 and 3,000 back in 2010.

“Author, Harry Dent, who has predicted booms and busts for decades with stunningly poor timing—for example, his forecast of a 17,000-point drop in the Dow in 2016—now predicts “a major financial crash and global upheaval that will dwarf the 2007-09 recession of the 2000s—and maybe even the Great Depression of the 1930s.

A better approach to investing amid the knowledge of past crashes is to accept they cannot be predicted consistently, and that they are reasonably frequent, and instead to remain invested with some cash on the sidelines to take advantage of the occasional irrationally cheap prices that transpire.

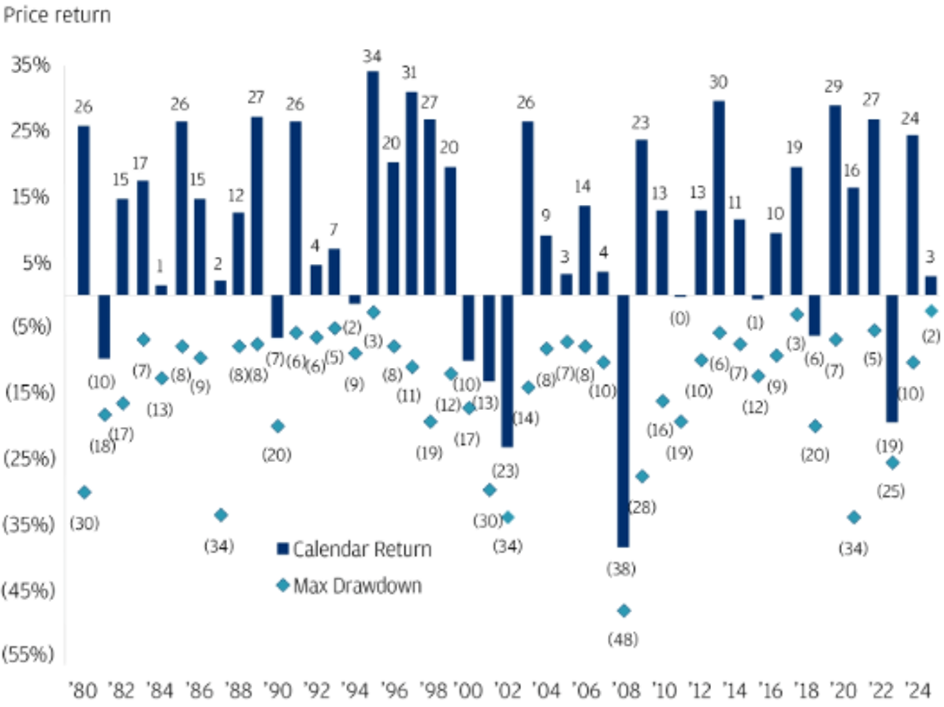

The problem with the tactical ‘all in’ or ‘all out’ method of investing is that while you may get lucky and miss the worst days, you are also equally likely to miss the best days. Volatility is a feature of investing, something that should be eagerly awaited rather than feared. According to JP Morgan (figure 2), since 1980, the S&P 500’s intra-year pullbacks have averaged 15 per cent, and in 16 of the last 44 years, the index experienced even steeper losses during any of those years. And yet, despite this, full-year results were positive 75 per cent of the time or in 33 of those 44 years.

Figure 2. S&P 500 intra-year declines (max drawdowns) & calendar year price returns

Source: FactSet, Standard & Poor’s, J.P. Morgan Asset Management

Source: FactSet, Standard & Poor’s, J.P. Morgan Asset Management

An investor who simply invested $100,000 in the S&P 500 index in January 2004, would have gained 9.8 per cent per year and have an investment worth $648,704 twenty years later. However, missing the ten best days would turn $100,000 into $297,357, and missing the best 20 days would have turned $100,000 into just $177,136.

There are always experts who claim they know the future and who compellingly argue their case for a crash. But, by following these experts, one is less likely to sidestep a crash than miss opportunities. The same can also be said for the events upon which many forecasters have based their predictions.

Table 1,,. reveals just a handful of examples of the events cited as reasons to reduce risk, take money out of the stock market and await a clearer picture.

Table 1. Recent examples of reasons not to invest.

Source: J.P. Morgan, Factset. Note: Cumulative Total Return is calculated from December 31 of the year prior to January 31, 2024

Source: J.P. Morgan, Factset. Note: Cumulative Total Return is calculated from December 31 of the year prior to January 31, 2024

As the Cumulative Total Return column (for a classic 60/40 portfolio) in Table 1., reveals, jumping out of the market when the clouds seem darkest is an expensive mistake. And you don’t get those returns back. Once they are missed, they are gone forever.

Nothing would delight me more than for younger investors to heed the mistakes of the generations before them. Technical analysis doesn’t work; charting is merely a clumsy way to try and identify trends, and short-term trading should be left to high-frequency trading outfits and the Medallion Fund.

Everyone else would be best served by investing patiently, and for the long term, in quality businesses whose value rises at a pace approximating the growth in the equity per share (roughly equivalent to the retained return on equity), or in a managed fund that seeks to do the same.