Are U.S. rate cut expectations reasonable?

The U.S. Federal Reserve (The Fed) has two main mandates: supporting employment and controlling inflation. Until Friday, it looked as if the two were almost perfectly balanced against each other, suggesting that the Fed would keep rates on hold in December.

Last week, Wall Street decided that a December cut was off the table. On Wednesday, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Fedwatch futures index placed the probability of a cut at just 30 per cent.

Meanwhile, JPMorgan published a note predicting a January cut. Markets sold off dramatically, with the Nasdaq 2.74 per cent lower, and the S&P 500 losing 1.95 per cent last week. And there were of course, fears of a bubble in the artificial intelligence (AI) theme, which we have written about here copiously.

This week, however, investors have assigned a 75.5 per cent probability to Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell delivering a rate cut in December. Renewed hopes of another round of cheap money are again fueling asset prices.

Why?

The U.S. government shutdown made employment data harder to come by, but most analysts think the labour market is getting weaker.

Back in September, the Federal Reserve cut rates amid growing concern over a weakening jobs market. After the committee’s two-day meeting, Chair Jerome Powell said on September 17, “I think we’re now reacting to the much lower level of job creation and other evidence of softening in the labor market,” adding, “…That warrants a change in policy.”

According to economists, the downside risks to employment have increased as the labour market has cooled, while the upside risks to inflation have lessened somewhat.

But not all economists and strategists agree. U.S.-based Apollo’s Chief economist, Torsten Slock, notes the debate over the Federal Reserve’s policy trajectory hinges on the underlying drivers of inflation.

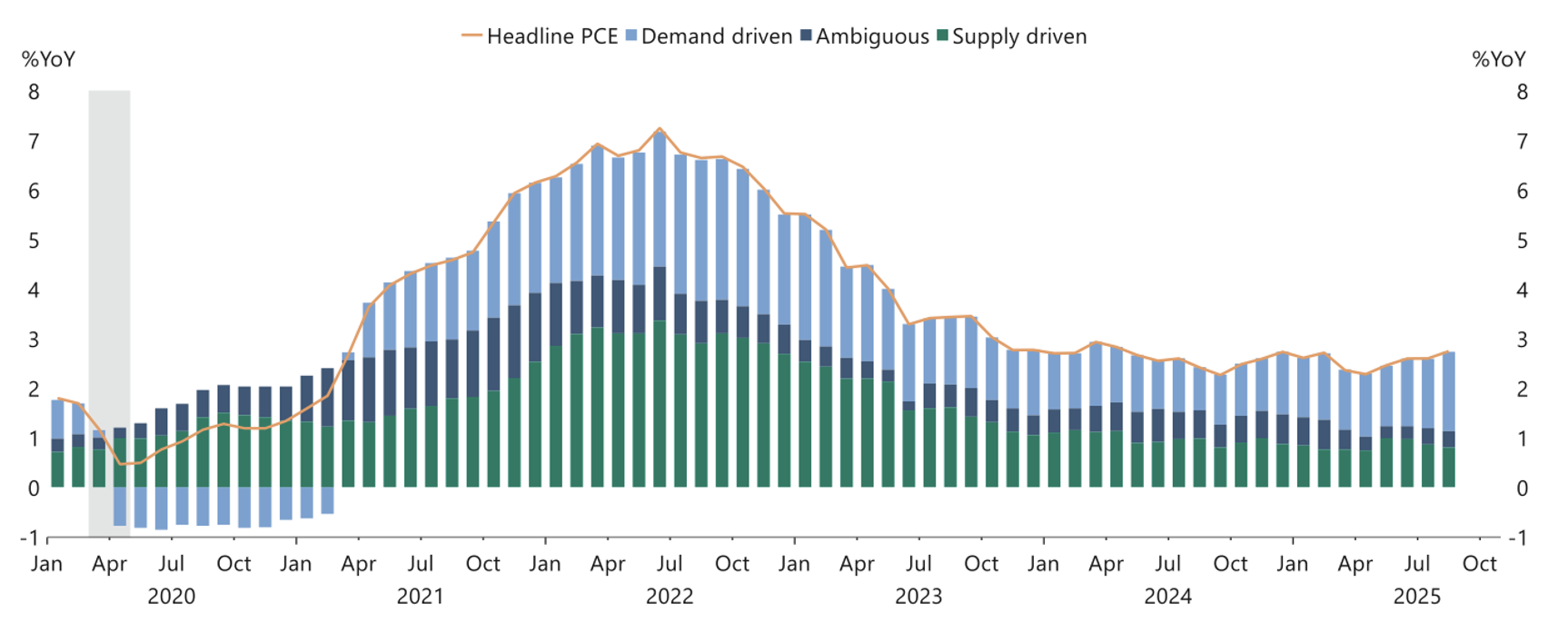

Figure 1. Two-thirds of inflation is demand driven, one-third is supply.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Macrobond, Apollo Chief Economist.

Slock cites a San Francisco Federal Reserve decomposition of inflation (Figure 1.) that reveals the current inflationary environment is largely a demand-side story, with strong economic activity accounting for most of the price growth.

As long as demand-pull inflation keeps the headline rate above the two per cent target, Slock believes “a higher-for-longer interest rate stance is required to bring the economy back into balance”.

Of course, if inflation were primarily a function of supply shocks, there would be no need for the central bank to keep rates high because it wouldn’t need to crush demand. It would be in a position to permit lower rates.

While the source of inflation remains the critical variable for the Federal Reserve to determine whether it needs to modify monetary policy, the U.S. central bank will have to go without labour and price data for the last two months.

On 21 November, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) cancelled the October inflation and jobs reports because the government shutdown rendered data collection impossible. The BLS will also delay the November jobs report from 5 December to 16 December, and delay the inflation report to 18 December from 10 December.

That means both reports will be released after the Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) 9-10 December meeting.

Consequently, economists note the U.S. Fed will have to rely on weekly state jobless claims, private payroll reports, and anecdotal evidence from the Fed’s Beige Book (a summary of commentary on current economic conditions), which covers all 12 districts, when determining its next rate move in December.