Is Big Australia a big mistake or a big lie?

Why do we have a housing crisis? We’re told it’s because there isn’t enough housing, so the price to purchase or rent is too high for young people. There’s no denying the truth of those two answers. One might, however, choose to dig a little deeper: Why do we not have enough houses in Australia, and why are prices so high?

When I google those questions, the answer generated is as follows:

“Limited land availability, slow modifications to planning laws, and global shortages of building materials have all contributed to the housing crisis in Australia. Geographical constraints have restricted the availability of land suitable for housing development, particularly in cities like Sydney.”

The University of Queensland (UQ), in an article entitled, Australia’s housing crisis.

How did we get here and where to now?, published in Contact Magazine, suggests;

“On one hand, we have disinvested in social housing and other forms of housing that are affordable. And on the other, there has been a lot done at the policy level to ensure housing is a commodity to be speculated on.”

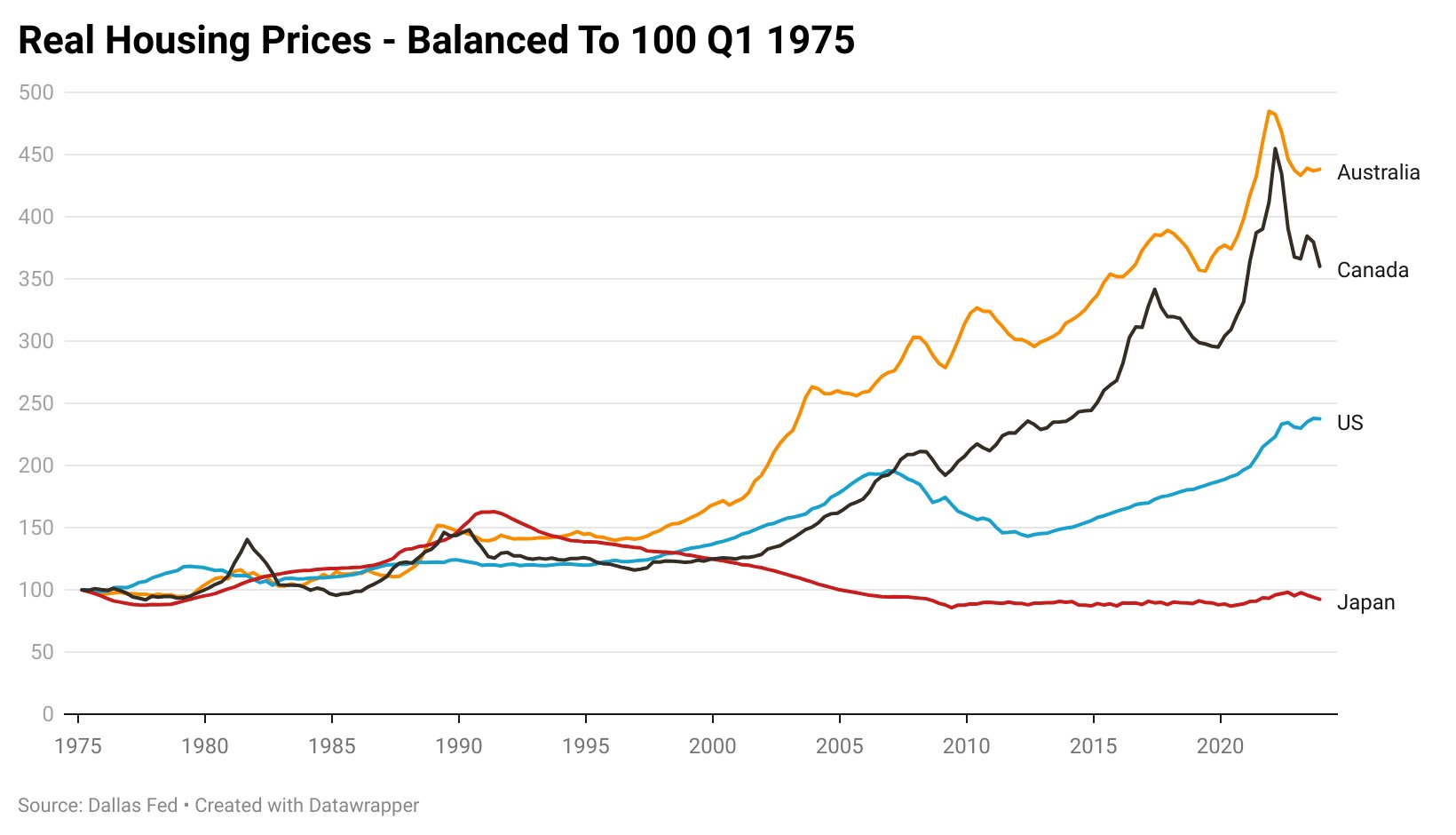

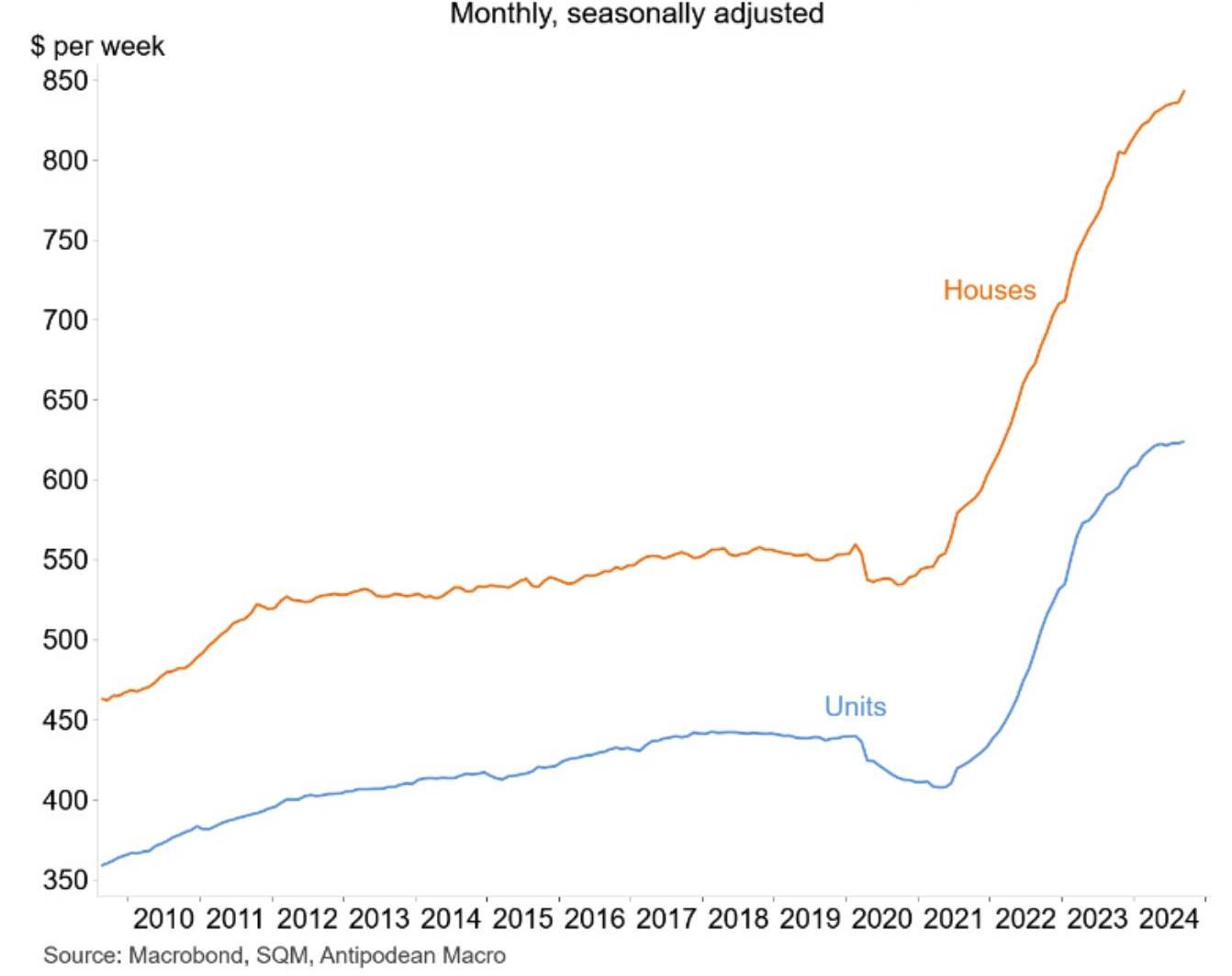

Sounds reasonable doesn’t it? It’s certainly an answer politicians would like you to believe. Figures 1. and 2., indeed confirm prices in Australia for purchase and rent have risen at an extraordinary rate and faster than salaries and wages over the same periods.

Figure 1., House prices rises in inflation-adjusted terms

Figure 2. Australia – capital city asking residential rents Source: Macrobond, SQM, Antipodean Macro

Source: Macrobond, SQM, Antipodean Macro

But are google’s and UQ’s answers the only answers?

For a shortage of anything to exist, demand must exceed supply. The answers provided by UQ and Google address the supply side of the problem (there is an estimated 200,000 to300,000 home shortage for our existing population), but, by definition, for a supply problem to exist, there has to be demand strong enough to exceed supply.

It’s economics 101.

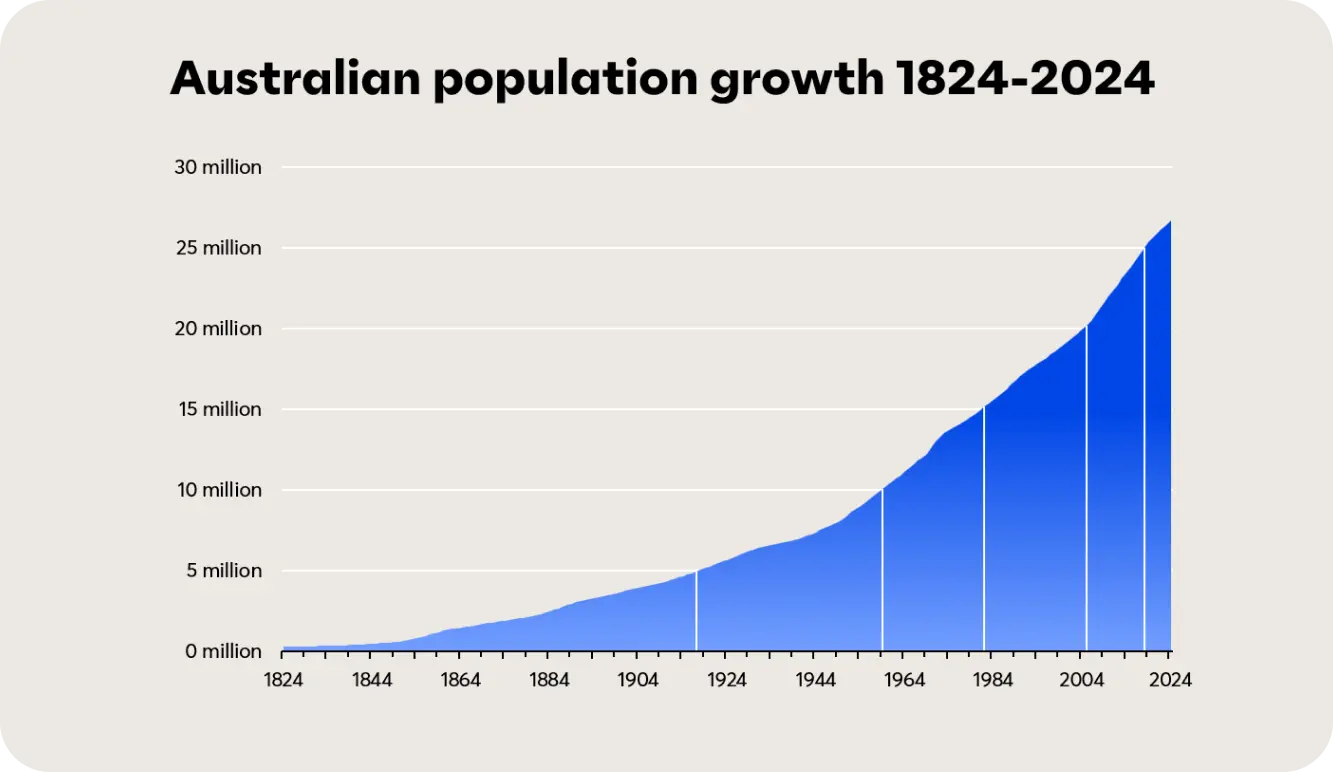

Could that demand be a function of population growth? We know there has been a population explosion in Australia (Figure 3.).

Figure 3. Australia population growth 1824-2024

Source: McCrindle

Source: McCrindle

Is the reason for the population explosion described in Figure 3., that we are all having too many babies? When introducing the baby bonus scheme in 2002 (remembered globally as singularly the worst policy created to encourage higher fertility rates), Treasurer Peter Costello famously encouraged Australians to “have one for mum, one for dad and one for the country”, and so we all jumped into the bedroom and started procreating. Or did we?

Sadly, that is not the case. Figure 4., reveals Australia’s birth rates have plunged well below the 2.1 children-per-woman ratio required to sustain a population. There was a bit of a jump after the baby bonus was introduced, but one-off payments don’t sustain a behaviour, and we quickly reverted to having fewer kids again.

Figure 4. Australia’s birth rate Source: IFM Investors, ABS, Worldbank

Source: IFM Investors, ABS, Worldbank

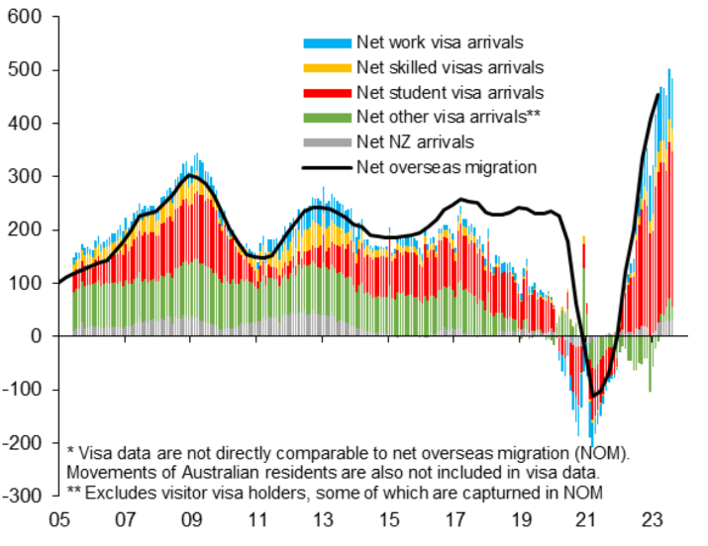

No, the exploding population is not from natural causes. It’s due almost entirely to migration – a social experiment that we will see is failing Australia and Australians on multiple levels. In 2023, between 518,000 and 528,000 new people called Australia home. In 2024, that number was lower but still an outrageous 446,000 people. Over those two years, migration increased Australia’s population by the equivalent of two Tasmania’s!

Figure 5. Australia – net annual overseas migration

Source: Macquarie Group

Source: Macquarie Group

According to The Australian Financial Review’s Education Editor, Julie Hare, the number of student, graduate, bridging and skilled migrant visas rose by 200,000 to 1.41 million over the 12 months to the end of August 2024. That’s 5.4 per cent of our pre-migrant visa population. That will have an effect on housing and on almost everything else.

Australia’s net visa arrivals are landing in Australia at an unprecedented rate with international students being the primary (50 per cent) contributors. Of course, lots of imported students competing for rental properties must have an impact on rents.

The Federal Education Department estimates that international students occupy seven per cent of rental properties. And at the end of August, there were almost 680,000 international students in Australia.

As many know, a proportion of these students are pawns in an international game of money siphoning out of China that sees families buy homes for children attending Australian tertiary education. That drives up house prices.

Many other students don’t study at all, attend ‘bogus’ courses for non-genuine students, or are here to work, switching to other types of visas and subsequently seek protection visas.

In other words, the housing crisis is actually a migration crisis.

To begin easing the housing crisis, the Government must first firmly enforce temporary visa conditions, meaning sending temporary visa holders home after their visas have expired. No exceptions.

And if you believe rampant immigration is having a negative impact on our culture and social cohesion there’s another reason to slow immigration.

But isn’t Big Australia good policy?

According to the Centre for Independent Studies, 2010 report Populate and Perish by Jessica Brown and Dr Oliver Marc Hartwich,, Australia’s growing population will benefit the economy as consumers, savers, entrepreneurs, and workers. They note more people will make it possible to increase the division of labour. It will open up new opportunities for niche products and services, which otherwise could not be offered. And it will also make it possible to provide better mass transit infrastructure for which we currently lack the capacity.

While some of the above arguments are circular – do we really need more people to make more products or a transport system that is required only if we have more people – we are also told that our skills shortage and full employment demand more people.

The realities are somewhat different because we don’t have systems, structures and conditions to support more people.

As has been reported widely, The Atlas of Economic Complexity, produced by the Growth Lab at Harvard University, measures the complexity of economies around the world. The researchers analysed 133 countries and placed Australia at an embarrassing 93 – almost the bottom quartile, ranking our economy less economically complex than Uganda, which was ranked 92. Both sides of politics should be ashamed of the deterioration in our living standards they have been responsible for engendering and presiding over.

Higher immigration won’t create the industries we need to increase our quality of life. They won’t build the industries that make our economy more complex.

Way back in the very early nineties my Melbourne University lecturer, Dr. Neville Norman, pointed to the idiocy and unsustainability of exporting raw wood chips to Japan, only to import the finished paper from Japan.

Today, three decades on, we export 20 tonnes of iron ore to import one iPhone 16 Pro Max. Worse, most of the revenue from the sale of that iron ore goes to just two families, the Rineharts and the Forrests. Sure, the Australian Government taxes their companies but all that does is incentivise them to minimise their profits, which reduces the tax take.

If the government had any sense, it would tax the revenue or insist on co-ownership of the mines that extract Australia’s resources.

Meanwhile, we ban coal mines and the installation of gas stoves in homes, but we sell the very same coal and the gas overseas at raw material prices, allowing the buyers to burn and use it without Australian gaining any economic benefit. Idiocy!

Talk about shooting ourselves in the foot! As one of the richest nations in the world in terms of energy and raw materials we should be one of the richest in the world financially. Instead, we are poor because we frustrate the economic advantages we have and instead impose restrictions on the use of those resources, systematically making us poorer.

Back in March 2013, I wrote a column for The Australian entitled, How to Become Poor: Sell raw materials, buy the end product. In that article, I called out the then Resources Minister Gary Gray. Without even a suggestion of a serious sovereign stake in our resource wealth, he suggested the answer to lower commodity prices was more volume. Idiocy.

That answer to a volatile raw material price is not more volume. It is adding value to it. The mining industry doesn’t employ a very high proportion of people so selling more won’t raise salaries enough to catch up to surging house prices.

A lack of sophistication in our economy and a lack of value-added exports however is guaranteed to keep wage growth low.

Of course, our tax incentives are all wrong to incentivise the start-up of an export value-adding industry. Meanwhile, the forced switch to unreliable sources of energy is making energy costs for businesses more expensive (both need to be fixed). Still, by adding sophistication to our exports and through sovereign co-ownership of our resource wealth, we would all earn more revenue, become wealthier and reclaim our once high standard of living.

That is, of course, the real crisis making us poorer, unable to afford more expensive housing that is driven up by stupid immigration policies. It’s all too hard for the calibre of our politicians, and in any case, the election cycle is only three years, so why would they bother (we also need to fix the election cycle)? Instead, we are told a distracting ‘porky pie’ that the real crisis is housing, and the reason for that is we don’t have enough workers to build more apartments.

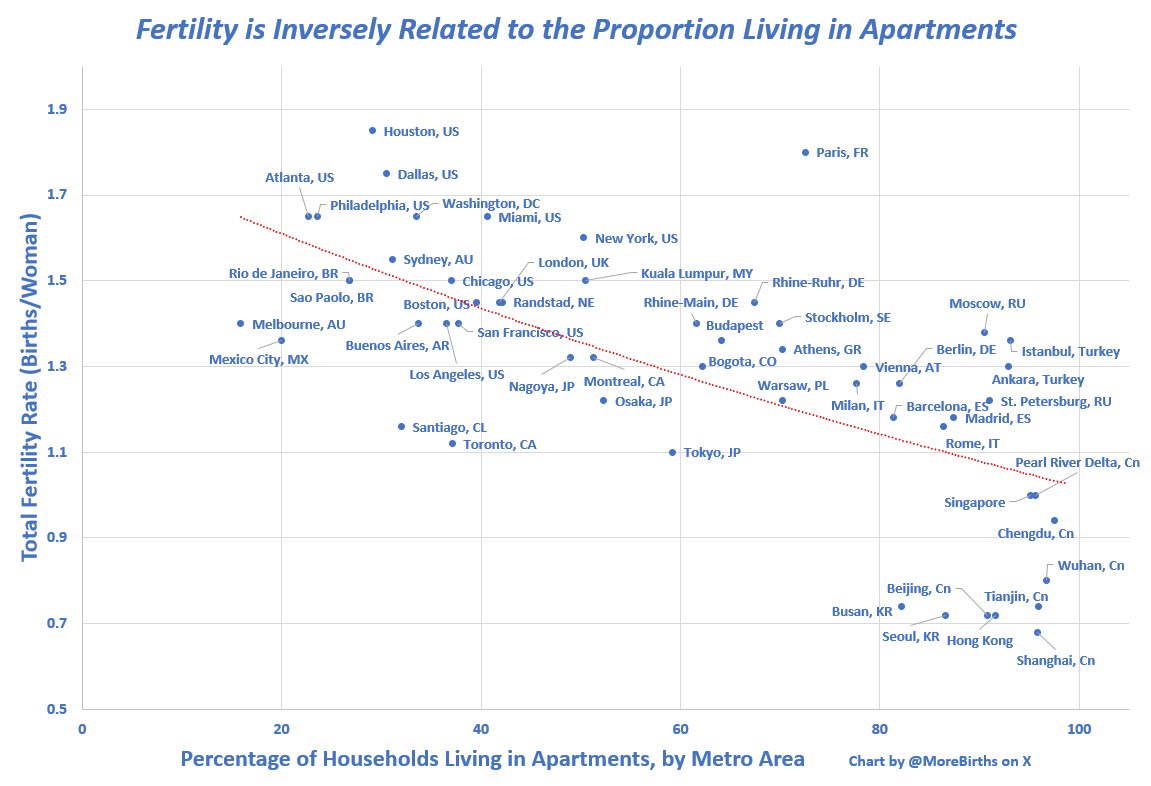

As an aside apartments aren’t great either.

Figure 6. More apartments equal fewer babies

Source: X, @MoreBirths

Source: X, @MoreBirths

According to our leaders, by importing more workers we will be able to build more apartments to house all the workers. The circularity is stunning. But the issue is that we are importing students, not skilled workers. If there really was a skills shortage shouldn’t the government be handing out visas to skilled workers?

If it now sounds just a little bit stupid, it is.

We are getting poorer, and immigration is making it worse, not better. The answer is not to knock down more houses and knock up more apartments. The answer is to slow or even stop migration for a period long enough to allow infrastructure to catch up and to fix the fundamental deficiencies the last thirty or forty years of government policies and ineptitude have created.

You can read the 2013 article here.

Great insight ts we cant deny the change we saw instantly as soon as the immigration levels increased. I work with a person who came here as an engineer but works in a service role. Looking at other data of how many of our so called skilled workers are under employed for their skills it looking like a big lie, the so called engineer unfortunately has some customers who are engineers, I cringe as they are floundering when asked engineer questions or opinions. I doubt very much they are qualified. As for the gentleman with the NIMBYISM comment stating thats why we arent building more homes, I doubt that also, I have had many apartments built literally in my back yard – over the limit of neighbourhood every single time, over scale, and overlooked as they go outside building times, flout the rules of sediment control and dust. So called Nimbys have no impact in my area, when a developer wants something council rolls over. If theres a delay its not the nimbys its just the developer waiting for other projects or the market to change. Only people who actually have developments in their backyard can judge others, I am yet to see someone throw around the NIMBY or YIMBY phrase who lives anywhere near these overscaled greedy and poor quality eyesores. If the apartments offered a good experience for living SURE but believe me they do not.

Thanks for sharing. I have a lot of sympathy for that view too.

Roger this is one of the best articles I have read for a long time. Well researched and thoughtful, unlike so many of our policies. But where is the will to change a broken political system? I don’t see it happening in our lifetime and our kids will pay the price through lower standards of living and a debt to match.

The three year election cycle needs to be replaced first, which, sadly will take some work. We need a term that allows government to actually achieve some things on their watch.

Economics 101 – demand creates it’s own supply.

Increased population doesn’t create a shortage or raise prices of milk or cars or furniture or any other man made good. In housing there are enormous barriers to building new housing and particularly cheap housing. In inner-city areas land is very expensive and hence apartments should be much cheaper than detached houses as they require less land and vastly less land for high rise. Nimbyism is cause 1 of the housing shortage.

The bottom 10 to 20 % of the population don’t have enough money to pay enough rent to induce privately provided supply. Falling levels of public housing is the other main cause of the housing shortage.

The stats suggest its more multi-faceted, so thank you for sharing those thoughts

Hi Roger. All we have to do is look at countries like Norway and we can see how incredibly wrong we have got it for the last 70 years. Obviously dont need big population , just a bit smarter management. Finally I believe the state government here in WA has incentivized Rio and BHP to build a green energy steel plant here. Its probably not high tech, but it will be value adding I expect.

The oil and gas industries play a dominant role in the Norwegian economy, providing a source of finance for the Norwegian welfare state through direct ownership of oil fields, dividends from its shares in Equinor, and licensure fees and taxes

Finally, someone calling it out for what it is…WEF sponsored and enacted by a traitorous PM…

Thanks for the encouraging words

I too was thinking of Matt Barrie when I read this. Hopefully if more people start saying this more loudly, the message might start getting through to the wider public. Not holding my breath though.

Yes, there are a few of us banging on about this. I have been talking about it since 2013. @MattBarry should consider funding a third centrist party (the ARP – Australia Realists Party anyone?). I’d join.

A good piece, Roger… and frustration shared by many.

Australia has all the resources required to be fully self-sufficient yet raw materials are exported only to be imported as consumable goods… just madness!!

Charlie Munger’s take on ‘envy’ being more damaging to society than greed and fear is on the money. When people holding a ‘stop-and-go’ sign are demanding, and getting paid as much as educated professionals, something is right out of balance.

I’m 55, and have never felt so uninspired and unincentivised to aspire when for starters, the rate I am being charged for electricity has increased 56% since May 2022 and all other living costs have increased north of 20% whilst salary has moved only 5%. Don’t even mention trying to buy a house… and I live in regional Qld… where property used to be affordable.

Great insights. Thanks for sharing from the coalface!

Hi Roger.

Thank you for an astoundingly accurate assessment of just whats wrong with Australia and how we have let it happen. Hopefully we will get some changes in direction this year and a Government that has the interests of the country at heart and not their own interests in retaining a cushy job and getting photo ops with anyone stupid enough to stand in front of a camera with them.

Ever thought of running for Prime Minister?? – you’d get my vote.

Thanks for the vote. However, if I was to join any of the major parties I would have to toe their party lines and adopt their policies, many of which I fear are suboptimal.

The challenge we have is government need to build more nursing homes and scale back NDIS.

I work in a hospital and alot of the patients are elderly with minor medical conditions that could be handled in nursing homes but no rooms available.

The other thing is with ndis we are keeping people at home when they should also be in nursing homes.

I live in a unit complex and a couple of people have home care. One person is having depression and a carer calls at time during day and another person is disable with mental issues who has 24 hour care.

If these people where in a home it would be cheaper to look after them and also these people could mix with people from their own era.

A person down the road from me got a brand new zigzag ramp put in on their house paid by ndis. Value for money it was very expensive as they might use it 3 to 4 times per week.

The point I am making is with more nursing homes it would free up housing for more families to move into area helping to build communities that are dying of old age.

This would also improve businesses opportunities with more people living in area.

It would also get people out of hospitals freeing up nurses and also more beds available.

We would also save on NDIS with one carer lookong after 5 to 6 people instead of paying higher wages to look after one client I their own home.

If we adopted some of the fixes suggested, we’d be a wealthier nation and governments could afford to build the hospitals and hospices required.

Well written article, outlining all the key elements of the Federal government’s massive Ponzi immigration scheme. It shows the shallowness and ineptitude and lies of their economic policies. It exposes a massive fraud on the Australian public!

Thank-you Roger Montgomery, please keep raising the issues.

Thanks for the encouraging words.

I continually write to my local member – Pat Conroy and government ministers as well as all the Greens asking why do we have such enormous immigration numbers? Occasionally I get a vague or rude response from the Greens but thats about it.

yeah, they have all bought into the big Australia story perhaps because fixing our fundamental failings is simply beyond their calibre.

Matt Barrie made some very similar comments, although he draws some interesting inferences from the data.

Yes, there’s a group of thinkers who are arriving at similar conclusions. Adding value to our exports is required so we can rely on current account surpluses rather than capital account suprluses. The first step is tax incentives for genuine start-ups that are focused on export value adding.