The relentless growth of U.S. government debt

I was very lucky to attend the Harvard Business School Owner/ Presidents Management program over the three years to 2006. In my class of 100 mature–age students, around half were from the U.S., and the remainder were from several other countries. I know it is a gross generalisation, but it would be fair to say the U.S. students excelled at any “marketing” related case studies but noticeably under-performed in any case studies related to “accounting”.

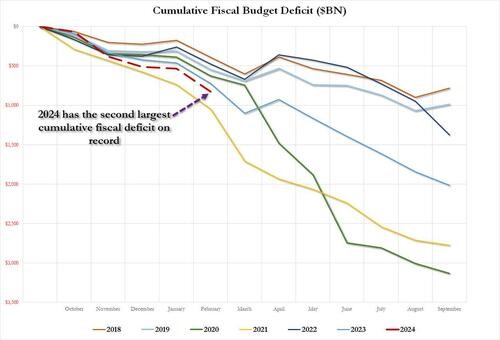

It is with that backdrop that I thought it worthwhile analysing the data released from the U.S. Treasury, post the release last week for the month of February, and the fiscal year to date being the five months to February 2024. In short, the data, on an annualised basis, is showing a budget deficit of U.S.$2.0 trillion (which exceeds 8 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) of U.S.$24.6 trillion), whilst the interest expense component of that deficit is running at U.S.$840 billion, or 42 per cent of the annualised budget deficit.

The U.S. Government Debt is now expected to hit U.S.$35.5 trillion at the end of the fiscal year (30 September 2024), around 144 per cent of GDP, and the trouble is this indebtedness is forecast to grow at a much faster rate than GDP over the medium-term.

The graph above illustrates a 10.4-fold increase in U.S. public debt over 33 years to 2023, with an average annual growth rate exceeding 7 per cent. While various governments may blame COVID-19, the cost of defence, demographics, health, welfare, or net migration, neither U.S. political party has striven for a budget surplus over the past 25 years. The problem associated with the increasing level of government indebtedness means any budget deficit will be starting the new fiscal year at close to U.S.$1 trillion in the red (or around 4 per cent of GDP), assuming reasonably steady interest rates.

Dissipating confidence in the U.S. dollar may be one of the reasons gold and bitcoin are challenging their record highs. And at some stage, “the market” may demand a higher premium over the level of inflationary expectations when lending the U.S. government funds. If the confidence level in U.S. bonds eventually comes under pressure, so logically, there will be many asset valuations.