What does the past tell us about inflation expectations?

In this week’s video insight David dicusses the official cash rates, noting that by historical standards they are still very low. It’s important for investors to think about the world before the low inflation rates of the 2010s decade, and simply accept that inflationary expectations may halve from around 8 per cent to 4 per cent but may not necessarily get a lot lower.

Transcript

David Buckland: Hello, my name is David Buckland and welcome to this week’s video insight.

This week I wanted to ask the question, whether the very low inflationary expectations in the 2000s and 2010s will be repeated – or should we look back at the 1990s for a guide to the future?

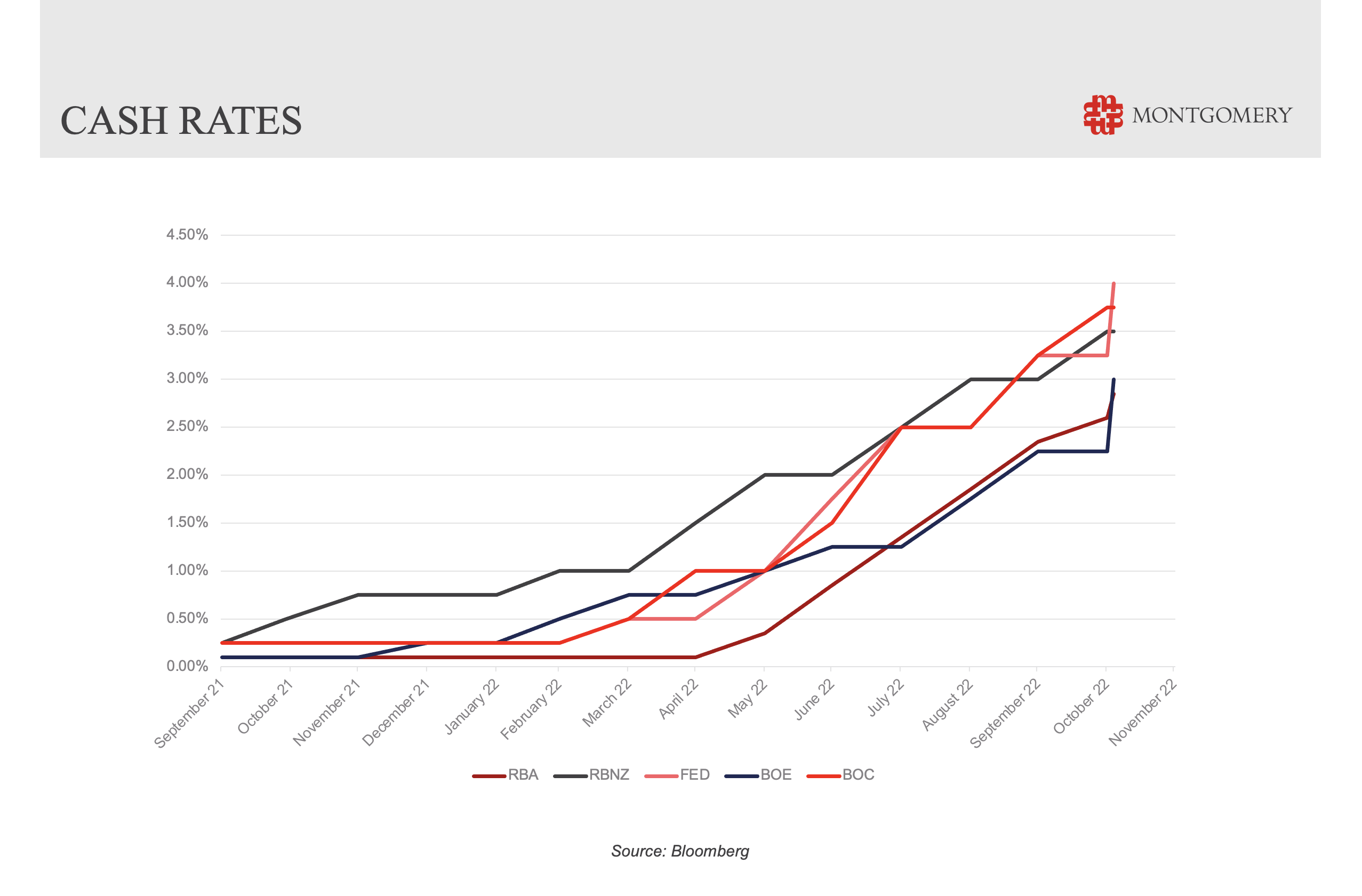

Of the five English-speaking economies highlighted in the graph below, the U.S. Federal Reserve has been the most aggressive by tightening its official cash rate to a range of 3.75 per cent to 4.00 per cent since March 2022. This move is the steepest increase in just eight months since U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman, Paul Volker, set out to crush inflation over 40 years ago.

Higher official cash rates in New Zealand (3.5 per cent), the United Kingdom (3.0 per cent), Canada (3.75 per cent) and Australia (2.85 per cent) will start to hit their more highly indebted consumers. Combined with high electricity, gas, fuel and food prices, these economies face a challenging outlook, and the record 50-year low unemployment rates will likely start trending up as corporates focus on costs.

Nevertheless, it is important to note the current official cash rates are very low by historic standards.

I think it is important for investors to think about the world pre the low inflation rates of the 2000s and 2010s decades, and simply accept that inflationary expectations may halve from around 8 per cent to 4 per cent but may not necessarily get a lot lower. That is the costs associated with many commodities, decarbonisation, infrastructure, defence, budget deficits and demographics may mean the typical one per cent to three per cent inflation target could be difficult to attain.

Across these five English-speaking economies in the 1990s, for example, we had official interest rates which were closer to double their current level, typically somewhere between five per cent and eight per cent. Meanwhile, US ten-year treasury bonds have sold off from 0.5 per cent in mid-2020 to above 4.0 per cent today, ensuring a significant sell-off in the valuation of many “growth assets”.

As English-speaking countries deal with higher inflationary expectations, investors are naturally going to be more conservative when chasing returns. Gambling on rising asset prices and leverage will be eschewed for high quality companies with good balance sheets and reliable cashflow.