Money for Nothing

Companies globally are using money for overpriced buybacks and inorganically-funded dividends. The result will be very low or negative returns to shareholders. It’s money for ‘nothing’.

Recently, in our blog post The End of the World as we know it (and I feel fine) we wrote about the current combination of bottoming interest rates, epochal levels of debt, declining productivity and full employment (which is tantamount to squeezed profit margins) and S&P500 price-to-earnings ratios of 18x being the complete opposite of the circumstances that existed in 1981 (a wonderful time to have invested) when P/E’s were 7x.

We referred to the fact that in 1981, when interest rates were 15 per cent and the real rate was 5 per cent, companies were forced to be judicious with their capital allocation decisions and restructurings were commonplace.

Today, a flat yield curve is paradoxically a disincentive to invest long-term. And when short-term interest rates are low or close to zero there exists an observable lack of judiciousness in the allocation of capital.

In 2014, the Chairman of Blackrock – a company our own head of distribution, Scott Phillips hails from – noted; “It concerns us that, in the wake of the financial crisis, many companies have shied away from investing in the future growth of their own companies. Too many companies have cut capital expenditure and even increased debt to boost dividends and increase share buybacks.”

And that was 2014. If anything the behavior has become more entrenched, encouraged by an eager band of shareholders who are suffering from an income recession – thanks to the low rates being earned on their cash investments.

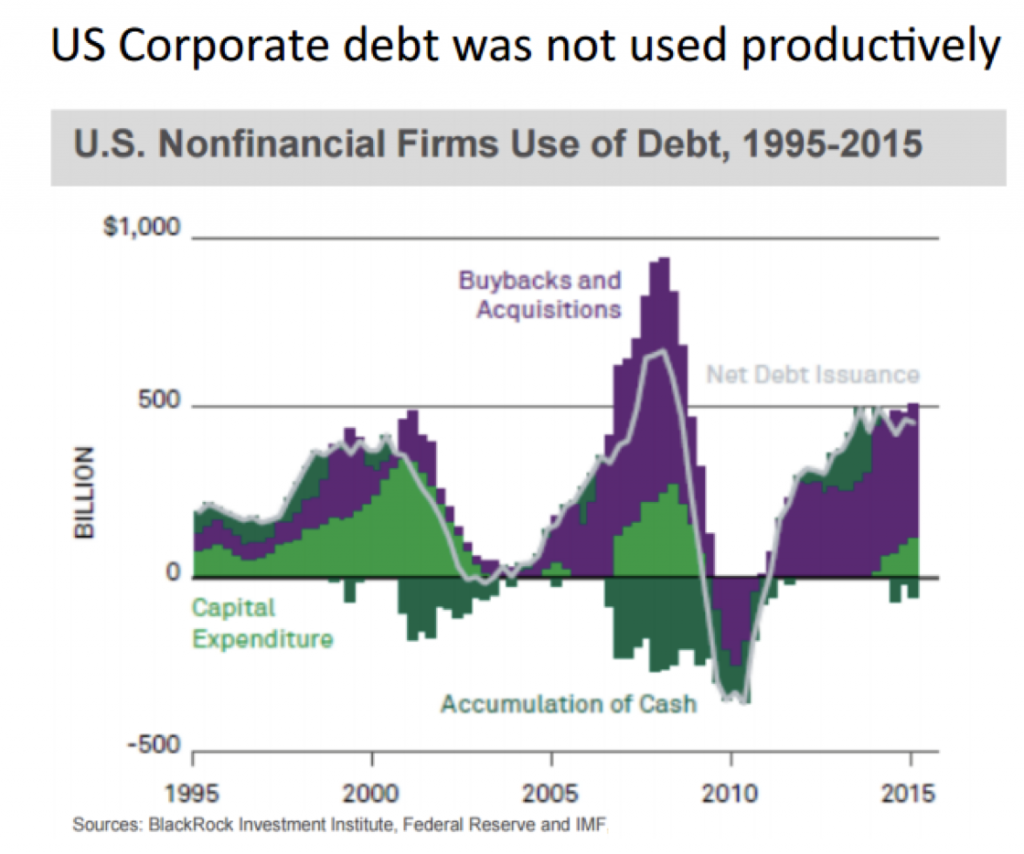

As the following chart, presented by Stan Druckenmiller at the Sohn Conference in May this year shows, since 2010 not only has the majority of debt borrowed been used unproductively it has been used specifically for buybacks and acquisitions (the growing purple shaded area).

Now remember that P/E ratios are at historic highs. They are in fact higher than they were at the peak prior to the Global Financial Crisis. Generally, the stock market is expensive.

As value investors we are interested in buying high quality companies only when they are cheap. That is how we have managed to outperform since the inception of our funds. When a company conducts a buyback it should also act like a value investor. If it overpays for its own stock, it destroys value rather than creates it. Companies, en-masse, are buying back stock at inflated levels. And they are using borrowed funds to overpay.

History tells me this won’t end well.

Dividends are dangerous

Another use for debt has been the payment of dividends. We have harped on for a very long time about the dangers of demanding higher dividend payouts from companies and simultaneously, the danger for investors of chasing high yield stocks.

You can subscribe and unlock our Whitepaper on the Dangers of chasing the highest yielding stocks HERE.

Companies are missing their cash flow and earnings targets, and analysts are reducing their earnings per share expectations. And despite this, companies are not missing their shareholder’s dividend expectations. These companies are either eating into retained earnings and/or raising their payout ratios. No matter what path they take, these companies are borrowing from their future growth to meet current demands for income.

Company boards are acquiescing to shareholder demands for dividends and they’re almost happy to oblige because the flat yield curve is a real disincentive to invest long term.

According to the Commonwealth Bank, three quarters of all companies surveyed maintained or increased dividends even though revenue growth was flat and aggregate net profits fell.

A 2015 study by our friends at Goldman Sachs noted $122 billion of free cash flow was generated by non-financial firms between 2010 and 2014 but those same companies returned $177 billion to shareholders through dividends and buy-backs.

The data confirms that Australia is following the same path as that which is observed in the US and articulated by Stan Druckenmiller.

By definition we don’t know what the black swan event will be that catalyzes a shift in sentiment. But history suggests something always emerges to reset the market’s compass.

Roger Montgomery is the founder and Chief Investment Officer of Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery, find out more.

Enrico Rumi

:

Csl has been increasing debt at low rates to buy back stock. Your thoughts to what happens when the music stops (rates go up but as it looks, I being of middle age, will not happen in my life time).

A side note, in the what if game, big opps coming with brexit. Built up cash. Ready Aim fire mms srx. Waiting to hear ur take on Ross tonite but unfortunately not. Too risky to take a position before. Reckon the best scenario would be buy with both hands on a leave vote although remain appears more likely (never underestimate inertia). I see a safer bet than hgg or btt which will b impacted but not to degree their stock prices will undoubtably reflect in the short term. Someone say Y2K. I wait salivating.

Peter M

:

Hi Roger,

I’m sure you agree the current PE ratio in the US is justified by the cheerleaders due to record low interest rates, similar to housing prices in Australia. Whilst I guess that there are financial models somewhere that would support this thesis, common sense would tend to indicate that record debt levels are going to cause a large number of bankruptcies when interest rates rise. Any Australian who entered the workforce in the last 25 years (myself included) has never worked in a recessionary period. Whilst that is extremely fortunate, I fear that many Australians have extended themselves a little to far courtesy off eager financial institutions. I can’t understand why people now consider the current financial landscape normal when 10 years ago it would be unthinkable to see trillions of -ve yielding bonds. When the worlds most successful money managers Soros, Druckenmiller, Dalio & Gross all seem to be cautioning that the generational debt party is about to come to an end, I would expect there to be a little more restraint. Nobody can say what the tipping point will be but looking at the upcoming brexit vote and us presidential election, there’s no shortage of catalysts!

Roger Montgomery

:

Good summary Peter. Thanks for taking the time to contribute.

Andrew

:

Hi Roger,

I read a very good book on this subject “Value.able” by R.Montgomery (do you know it?)

In a similar vein, what is your view on REA’s latest acquisition (Flatmates.com.au)? Was it a smart buy for them? Has it changed their valuation in your estimate?

Interested in your thoughts.

Andrew

matthew russo

:

Hi Roger

There have been several posts on the blog over the past couple of years outlining the above point of view and for what its worth being an accountant myself I fully agree with the above points which are supported by economic fundamentals.

But to what extent can historical principles be extrapolated into current the current environment? Developments in technology over the past 5-10 years have been unprecedented. Numerous times on the blog has it been mentioned that corporate margins are at record highs with the implication that at some point they will mean revert. But never before have businesses such as Amazon/Facebook/Google existed. Businesses that are able to develop such significant scale and influence off such a relatively small cost base and a model that employs where salaries and wages costs are spread across fewer people. These business are able to disrupt the business model of the incumbent and acts as a deflationary force in the market.

So whilst the GFC is seen as the underlying cause of the hangover we currently have, what if the blame for GFC has actually masked a fundamental change in the way the corporate environment? Perhaps the role technology is playing in creating the deflationary environment we are currently in is being understated. In which case is the eventual recovery we are all expecting from the GFC ever going to materialise or are we in a “new normal” of low interest rates?

The discussion can go on further by pointing out the fact that the worlds population (or at least the population of the developed nations) now forms a labour force which is far to large for a the modern corporate world.

P.S. I’m not a fan of the phrase “new normal,” but merely playing devils advocate.

Roger Montgomery

:

It’s always tempting to think ‘this time is different’.