Why it pays to harness diverse views when forecasting

“It is far better to foresee even without certainty than not to foresee at all,” wrote French mathematician, Henri Poincare. It’s a comment that’s really pertinent to us as investors. Here, I’d like to share with you some insights on how to improve your ways of ‘foreseeing’.

When forecasting company returns, we are trying to predict an uncertain future. Now, there are infinite possibilities for the future, so as investors we try and narrow these down to a more manageable number of outcomes – perhaps a base case, bear case and bull case, or a base case with a range of sensitivities.

But how do we come about choosing these scenarios? How can we be sure it’s the “best outcome”?

Firstly, we can ensure that we do detailed research and have a thorough understanding of the company and the environment that it works in. We can get our head around all the known knowns and as many of the known unknowns as possible (for more detail on this see our piece on Chuck Norris). This analysis will lead us to an optimal solution. But how do we know if this is the best solution? Can we do better?

A friend recently got me thinking about this when he pointed me to a paper on diversity by Scott Page[1]. Page highlights that whilst all problem solvers can find a local optimum solution, the global optimum does not necessarily coincide with the local optimum.

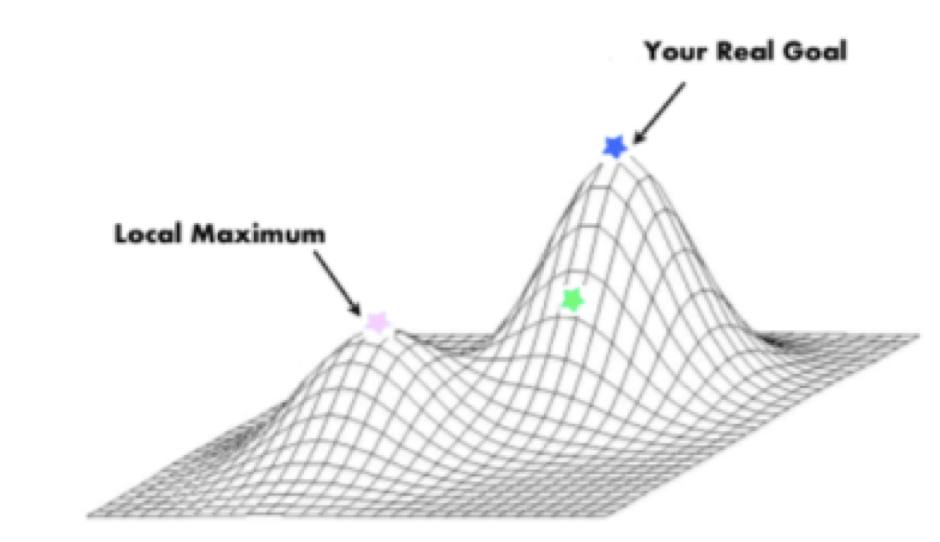

Let’s break down what this means. In mathematics we sometimes talk about a local solution versus a global solution. This picture may help illustrate the concept:

Let’s say your goal is to reach the highest peak. You know how steep the slope is where you are and you can walk around the surrounding area. How can you tell if you’re at the pink star or the blue star? In either case the ground has flattened at the peak. The pink star is a ‘local solution’ to the tallest point – however the blue star is the best ‘global solution’ to the puzzle.

But, how is this relevant to investing? Whilst we aren’t climbing to the highest peak when we’re forecasting – we are trying to find the most likely outcome.

Our goal (or highest point) is not to summit, but to value a company (or predict its future returns). Our slope is now the data we have and the conclusions we draw from it. If we use as much information as we can (or get as many slope data points as we can) then we should maximise our chances of reaching the highest peak.

Once we’ve done a thorough in-depth analysis we will conclude that the data we see points to a solution. This solution will be our local maximum – our best solution for the information we’ve been given. So how do we know if we’re the pink star or the blue star? The winner or the runner-up? How do we know if we’ve covered the whole board?

This concept shows us that sometimes we need to think outside the box, we may need to step away from a local maximum to reach the global one. So how do we do that? Page’s paper finds that increasing diversity leads to more frequent global optimal solutions. This is because we are increasing the number of perspectives, or possible interpretations that can be made. We’ve spoken about this concept earlier as “thought diversity”.

Talking to someone with a different perspective can increase the scope of outcomes you explore – it can help you think outside your box and re-interpret the information in front of you. This gives a lot of merit to investing as a team. To quote Aristotle… the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

[1] Scott Page, 2009, The Difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools and societies.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

G’day Lisa,

Great analogy that helps illustrate the point, but is this just an analogy?

Have you found the general technique of gradient ascent/descent of a chosen a metric to be useful in the world of investment analysis?

Cheers,

Mark

Hi Mark,

Thanks for the comment. There’s indeed a lot of both academic and broker research done on this topic. This particular piece is based on an academic piece of literature by Scott Page which is referenced at the bottom of the article.

Here’s another Harvard study illustrating the returns on diversity investing (in particular at the board level ): https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2017/03/16/diversity-investing/

The gradient analogy is a metaphor for information (the gradient) and reaching a conclusion (the peak).

Hi Lisa, that’s great, but in practice the real problem is how does a fund manager/ chief investment officer with a few years of consecutive good calls maintain the humility to listen to other people? This is very much a problem of human nature, not one lending itself to easy solutions.

Kelvin

Hi Kelvin,

Humility is certainly important. My point is that limiting yourself to a small pool of information and just your own perspective is not likely to lead to the best solution consistently. Being open-minded, listening to a range arguments and thinking outside the box is a better strategy. You’ve reminded me of a quote a good friend once told me from Arthur C Clarke (British Science fiction writer), who classified two kinds of failures – a failure of imagination (not thinking outside the box) and a failure of nerve. Both can be expensive errors to make.