Wealth Management Products make China’s shadow banking system a ticking time bomb

While western stock markets have continued to enjoy euphoric conditions over the past month, the Shanghai Composite Index has gone the other way, declining 7 per cent. One key reason is the ballooning problem associated with Wealth Management Products (WMPs).

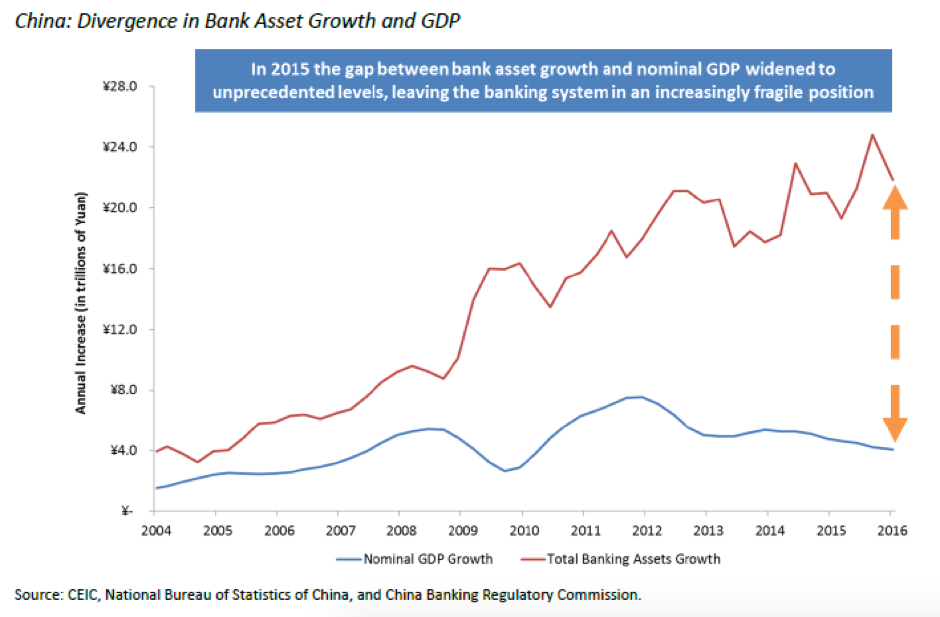

While the Chinese economy has been growing at a near 10 per cent annual average rate over the past three decades, there is limited understanding that much of this growth over the last few years has been debt-induced. The gap between bank asset growth and nominal GDP growth has widened to unprecedented levels, leaving the Chinese banking system in an increasingly fragile position. This is very concerning, because credit-induced booms rarely end well.

The Chinese banking system has grown at an unprecedented 25 to 30 per cent annually over the past decade to approximate US$35 trillion, over three times the country’s GDP. (When the GFC began, the US banking system approximated one times the country’s GDP). Chinese Banks are only allowed to lend out 75 per cent of their deposits to maintain healthy balance sheets. However, to circumnavigate the rules, WMPs were devised to pay higher yields than traditional deposits due to the increased risks associated with their investments. While the WMPs generate both fee and spread income, they are not consolidated on the Chinese banks’ balance sheets, and now have an estimated value of US$4 trillion, or 12 per cent of the banking system.

As the WMPs begin to fail – the underlying assets no longer cover the guaranteed interest and principal payments – many issuing Chinese banks have chosen to make up any shortfall. As those banks accept the position of implicit credit guarantor, the WMPs are brought back on to their balance sheets and China’s shadow banking system is slowly recognised as a ticking time bomb.

Some commentators estimate a 10 per cent loss of bank capital or US$3.5 trillion will be required from the Chinese Government to recapitalise the banks. With the Chinese economy being “overweight” construction, real estate and infrastructure investment activity, this will spark a deflationary scare around the world, leading to pressure on commodity prices, much like we saw in the latter part of 2015 and very early 2016. Likely lower Chinese interest rates accompanied by pressure on the Renminbi will be the obvious policy options.