US cash rates up from 0.5% to 3.5% in the three years to late-2019

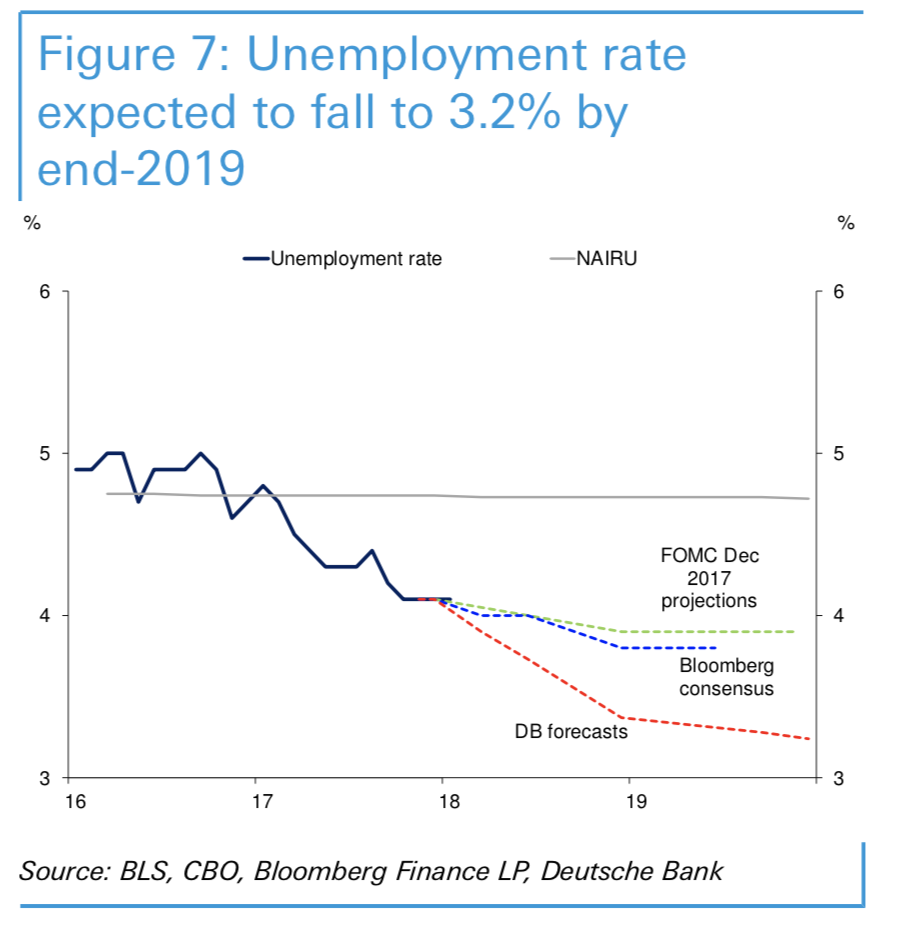

If our friends at Deutsche Bank are right in forecasting the US unemployment rate to decline from the current 17 year low of 4.1 per cent to 3.2 per cent by-late 2019, the US Federal Reserve are going to have a delicate balancing act as they lift the cash rate in trying to keep inflationary expectations under control. When I say a delicate balancing act, it is interesting to note the US Federal Reserve has historically, during these periods of rising inflation, tightened the cash rate to a real 1.25 per cent.

Over the twelve months to December 2017, the US cash rate was increased on four occasions from 0.5 per cent to 1.5 per cent. The consensus view is that process will be repeated in 2018, with the US cash rate ending the year at 2.5 per cent.

If Deutsche Bank are correct on these two fronts – a further decline in US unemployment coupled with a 1.25 per cent real cash rate – then 2019 would see another year of monetary tightening, with the cash rate then jumping to 3.5 per cent.

Let’s continue with this thesis which would see the US cash rate up from 0.5 per cent to 3.5 per cent in the three years to late-2019.

- Growth in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is faster than consensus, with the unemployment rate declining from the current 17 year low of 4.1 per cent to 3.2 per cent;

- Even though US ten-year bond yields have risen from 1.36 per cent to 2.95 per cent, up 1.6 per cent over the past eighteen months, the sell-off continues as the growth in hourly compensation and the corporate tax cuts boosts inflationary expectations;

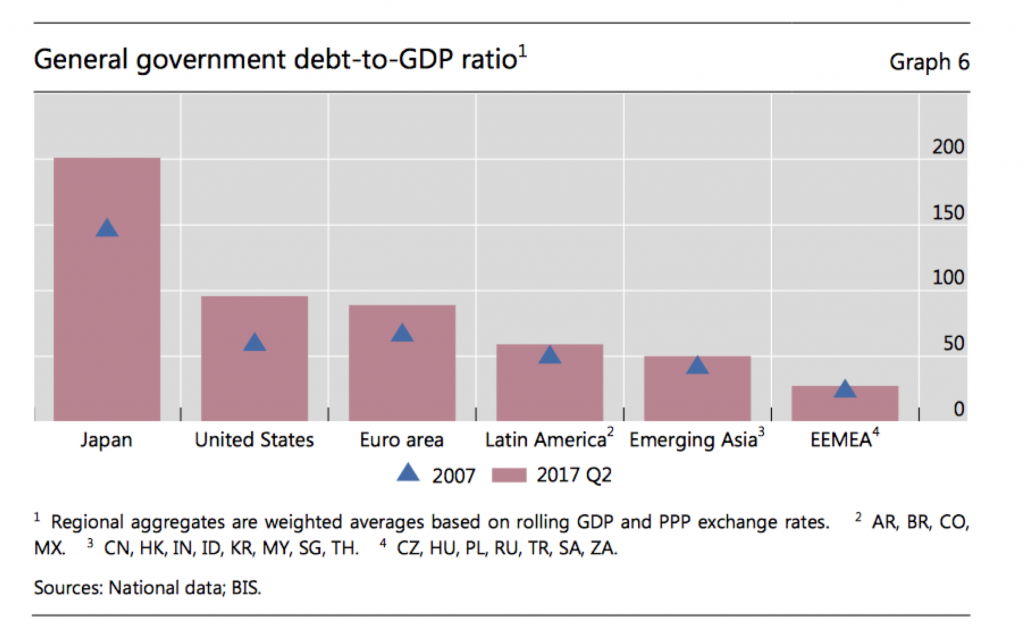

- The US fiscal deficit is projected to reach 5.4 per cent of GDP in 2019, a level reached only previously during the GFC, and the trend for the US sovereign balance sheet (debt-to-GDP) is worse than consensus;

- A potentially stronger US Dollar from rising interest rates would be associated with tighter financial conditions, particularly in Emerging Markets, where portfolio outflows could be expected; and

- Expect greater volatility across various asset classes (including foreign exchange markets). Given the Advanced Economies’ general government debt to GDP ratio – up 30 per cent in the past decade, as detailed in the graph below – corrections would be amplified by leverage.

Footnote 1: Bank for International Settlements: “How to transition out of a “Goldilocks economy” without creating a new “Minsky moment”?