Two reasons we don’t invest in mining firms

As most of our readers likely know, you are very unlikely to see any Montgomery managed funds invest in mining companies. And recent news out of China supports our investment approach.

There are two very good reasons we don’t invest in mining companies:

- We struggle to classify mining companies as high quality for a host of reasons. The most important is that they generally do not earn a return above their cost of capital over the cycle. They are also complete price-takers with no ability to influence the price they get paid for their products.

- Investing in mining companies therefore essentially comes down to making a call on the price trends for the commodity that the companies produce, and we don’t feel we have a particular edge compared to investors (or traders) that specialise in doing so.

The business model of mining companies (as for other resource companies) is based on making very large investment decisions in assets that will then provide output for many years to come. When taking the decision to make a major investment in a mine, a company must make assumptions on what the long-term demand for the output of the mine will be, and, hence estimate what the price is likely to be.

The problem is that a lot can change with demand and, once the investment decision is made, you are basically stuck with a mine for a long period of time and basically have to produce no matter what you get paid for your product as long as the price you get is higher than your marginal cost of production (not including any return on the investment).

Take what’s happening with China’s energy production, for example.

We note some news headlines as the annual United Nations environment conference kicks off this week.

When the Paris climate change agreement was signed in 2014, China committed that their CO2 would peak “before 2030”. This was seen as a very ambitious target at the time but the new forecasts that are coming out are that China will actually hit this target up to a decade earlier than previously thought. We therefore decided to take a look at some data on energy consumption in China.

When it comes to energy data, BP Statistical Review of World Energy is one of the more comprehensive and well regarded publications and is widely accepted as very accurate even though it is compiled by a major energy producer. All the data in the charts below comes from that publication and from the excel sheet that can be downloaded from BP’s site.

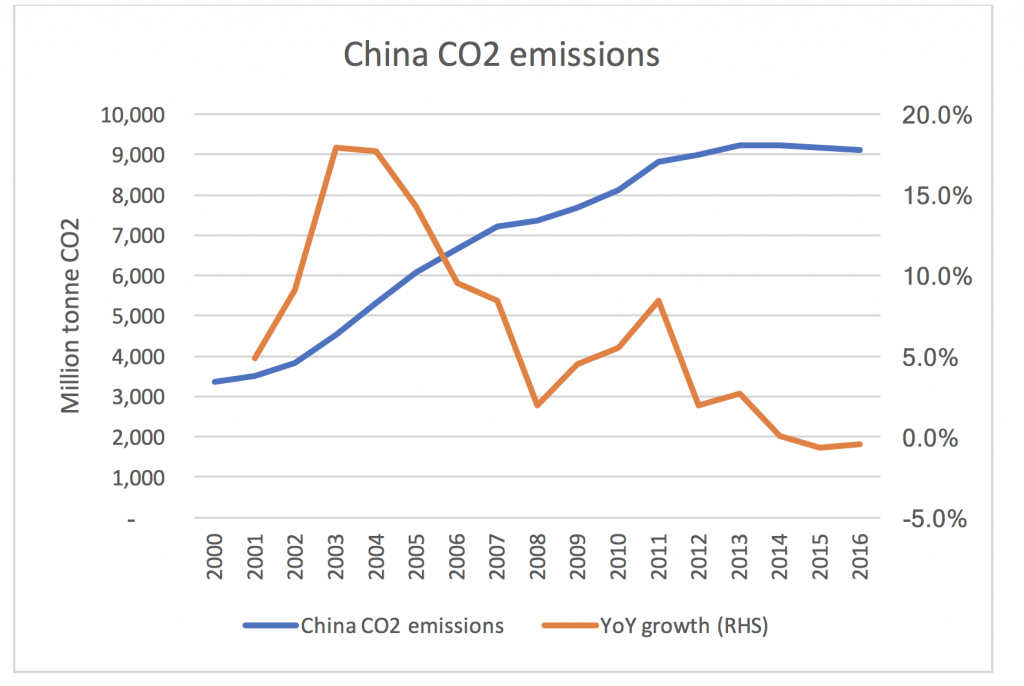

First let’s look at the CO2 emissions in China:

We can see that the emissions indeed are looking to be very stable and have actually been in negative year over year (YoY) growth territory the last 2 years.

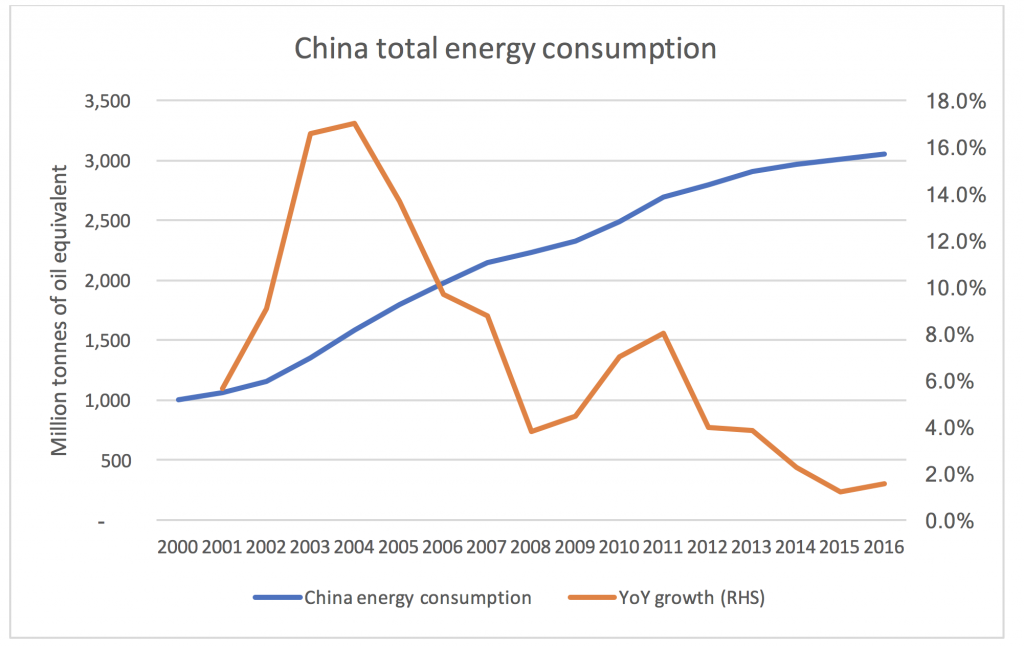

Next, let’s look at the total energy consumption to get a measure of what is happening to the key underlying driver: energy consumption.

We can see that the growth in energy consumption has clearly slowed down in recent years, but it is still growing by ~1.5 per cent per year so this does not by itself explain why carbon emissions look to have if not peaked, at least plateaued.

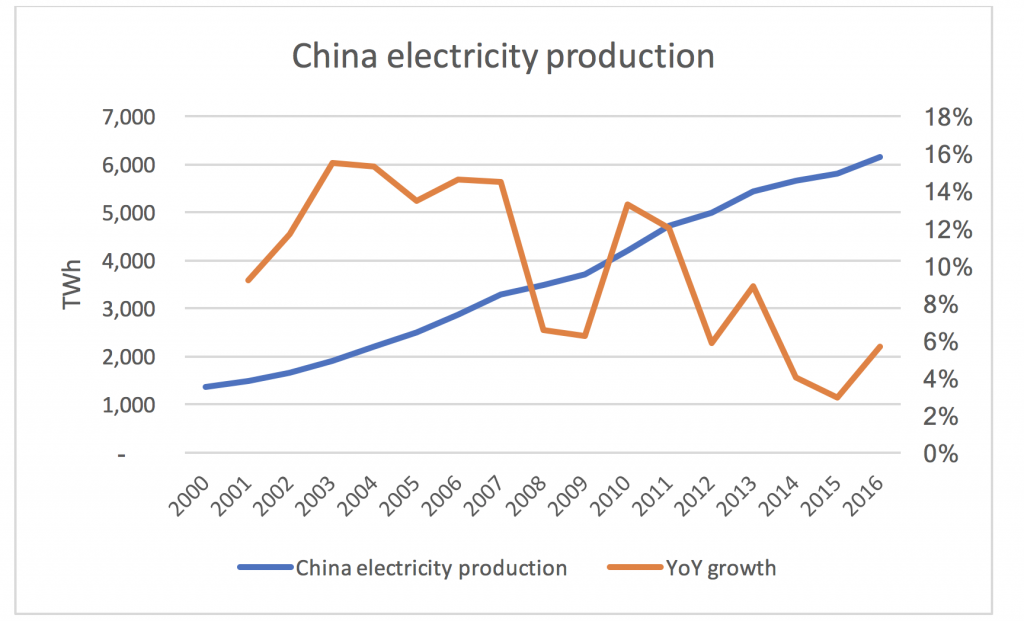

And if we look at electricity production (coal is the “worst” CO2 fuel and is primarily used for electricity production), the picture is actually even more confusing:

The chart shows that we are indeed seeing relatively strong positive growth in electricity production in the last couple of years.

So, if total energy consumption is up and electricity generation is up even more, what is happening?

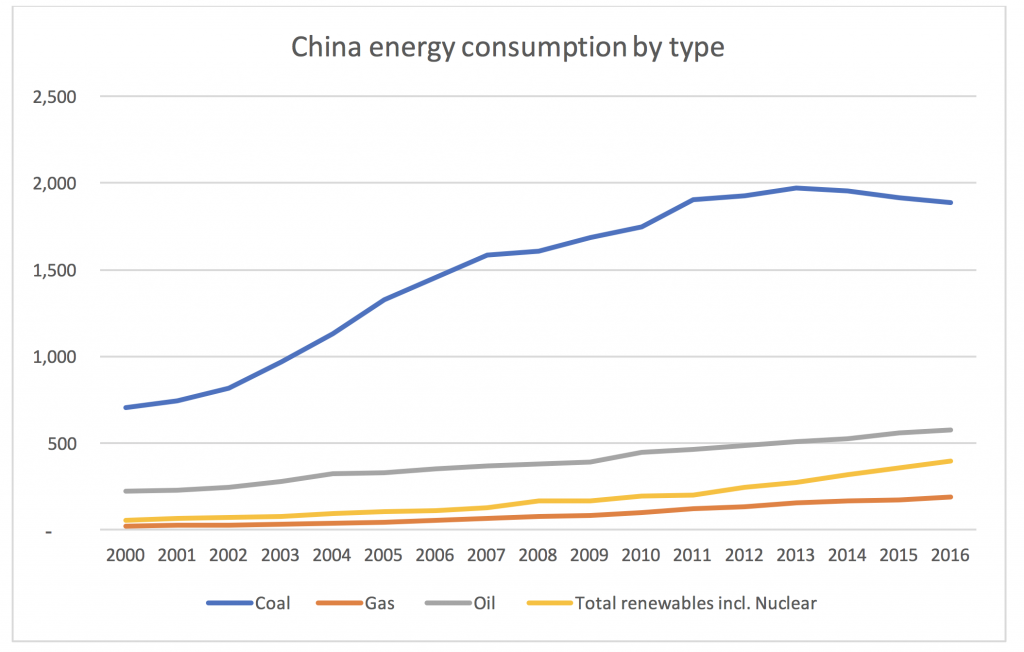

To understand what is happening we need to look at the breakdown between the different types of “fuels” consumed (technically renewable energy “fuel” is not consumed in the same way as fossil fuel based energy but for this purpose it is useful to think about it in this way).

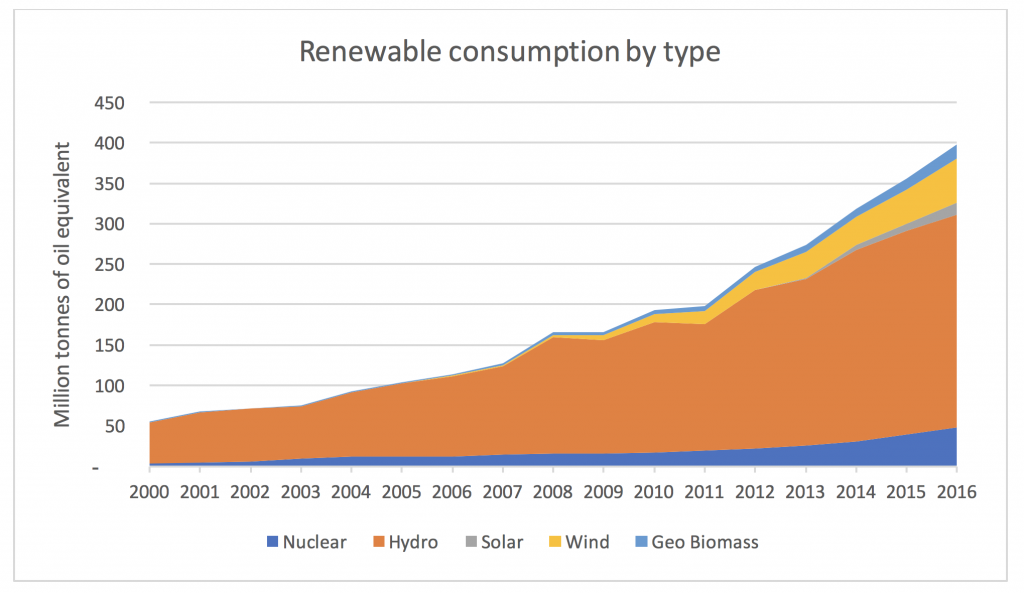

In the chart below, we can see the consumption by type; to make it easier to read the chart, we have grouped all the “non-emission” fuels together and included Nuclear in the non-emission group:

We can see that although China continues to see growth in its oil and gas consumption, coal consumption is indeed going backwards, having peaked in 2013, while renewables including Nuclear are growing very strongly.

And if we look at the type of renewable, we can see that the major contributor to the growth has been Hydro but that recently the portion coming from Wind and Solar is increasing rapidly.

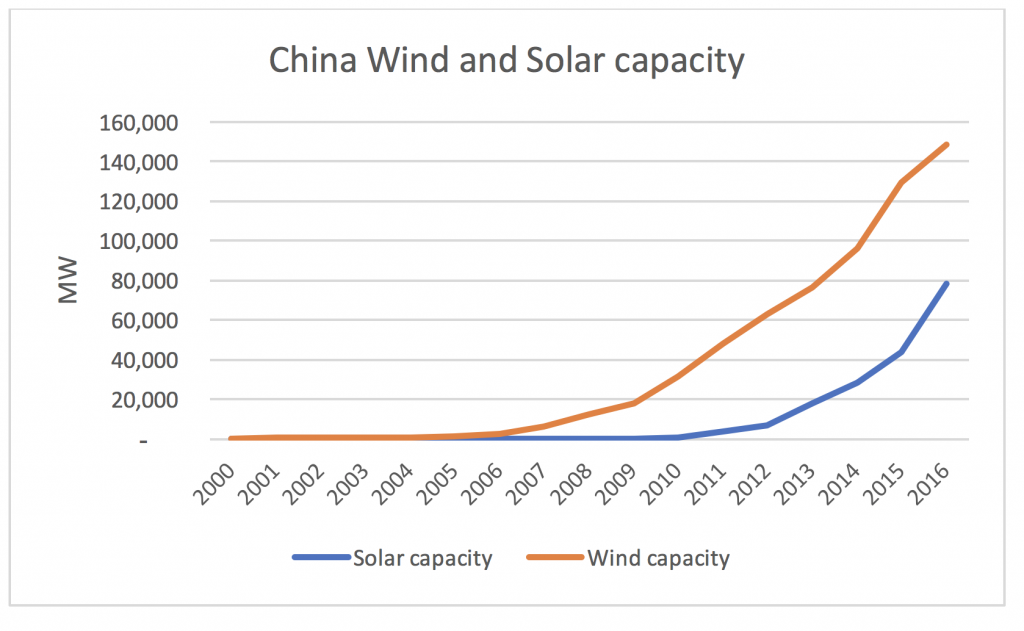

Given the strong growth during the last couple of years of Wind and Solar, the consumption figures above are actually a bit misleading as they underplay the growth of wind and solar capacity being installed as capacity installed during the year does not contribute for the full year. If we instead look at the installed capacity at year end of Wind and Solar, we can see that the curves are indeed exponential looking:

So, what does this have to do with investing in mining companies?

The reason we look at this is because we very much doubt that the rapid growth of wind and solar power, driven by very steep cost reductions over the last 7 years, was factored into the investment decisions that mining companies took over the last few decades. (Over the last 7 years, solar levelized cost of energy (LCOE), (which is a measure of the total cost of energy coming out of a power station including capital as well as operating costs) is down ~66 per cent and wind LCOE is down ~30 per cent.)

This change has happened very quickly, and changes like this are one of the reasons we do not feel comfortable investing in mining companies as they have a very limited ability to react to such rapid change given the very long investment cycles.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Btw also, the LCOE estimates you use for solar and wind do not take into account the cost of battery storage to compensate for their intermittency. Intermittent energy sources can be accommodated by the grid when they represent a very small proportion of the total, but once they grow past a point – say into the double digits of total generation – they start to destablise the grid, which relies on a finally calibrated real time balance between demand and supply being maintained at all times, along with high degrees of reliability.

The cost of offsetting the destabilising impacts of wind and solar, as well as providing back up generation to compensate for unexpected solar and wind downtime, have had to be borne by traditional generators. This is unsustainable. At some point capacity availability payments will have to be made to these generators in order to ensure the system’s sustainability/viability.

For solar and wind to be considered genuinely competitive with traditional forms of generation, the LCOE including battery storage that smooths intermitency needs to be considered, not the raw generation cost. On that basis, solar and wind are currently extremely uncompetitive. Costs have been coming down, but it is not yet clear if it will be physically possible for costs to fall enough for them to be cost competitive with coal and gas. Battery and solar tech does not follow Moores Law –

it follows the laws of physics. That still remains to be seen.

We can’t know for sure, but we can’t know anything for sure in markets – we need to work with probabilistic assessments of the future and consider a variety of future outcomes. Saying ‘we don’t know for sure so we won’t invest at any price’ is a somewhat bizarre approach imo.

I don’t understand the logic of so-called value investors saying ‘we don’t invest in these types of companies, irrespective of price.’ Price is everything when it comes to investing. Value investing is not about finding quality businesses or businesses that can grow, but undervalued companies. This is really value investing 101 but it is so often forgotten, even by the supposed professionals.

As a hard-core value investor, I salivate when I hear other putative value investors talk like this. It means there are large swathes of the market that are neglected and ignored by one’s primary competitor in the market – other value investors – irrespective of price.

At the right price, mining companies can be superb investments. South32 or instance traded down to one third of tangible book in early 2016, with a strong balance sheet, good management with cost initiatives underway, and solid assets down the cost curve. A good to great outcome was basically assured for any patient value buyer who was willing to wait. Mining services has also been a faboulous hunting ground over the past few years. Ausdrill got as low as 0.1x written-down book – an absurd valuation – and has more than 10-bagged over the past 18 months.

A low cost mining operation has a structural/geological & durable competitive advantage vs. its peers. Provided that commodity is not rendered obsolete & is still needed by the world, it is about as reliable a business as one can find – a business that is virtually certain to generate cash over time. At the right price – e.g. at or below replacement cost, or at low cash flow multiples on commodity price assumptions well below the top end of the cost curve – such companies can be exceptionally good investments with exceedingly low risk – exactly the types of asymmetric value opportunities genuine value investors should be looking for.

A good company is not the same thing as a good stock. This basic fact is forgotten so often.

Great article, thank you. Very interesting perspective to compare the time horizons of mining company developments vs renewable energy cost profiles.