Treasury Wine Estates – Part 3

In the third part of my series on the initial assessment of the investment case for Treasury Wine Estates given its leverage to a falling Australian dollar, we look at the influence of industry structure on returns and the potential upside from the falling AUD.

As noted in the last part of the series, the current share price effectively factors in more than all of the upside in earnings and returns from benefit of the fall in the AUD to current spot levels.

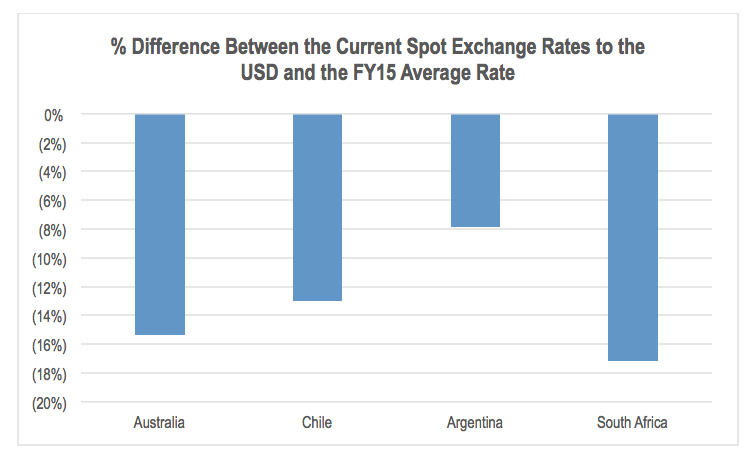

Additionally, this assumes the company is able retain all of the FX benefits (ie higher export margins) resulting from the lower AUD. This is unlikely given most of the new world wine producing countries that compete with Australian wine in key export markets, such as Chile, Argentina and South Africa, have also experienced significant currency depreciations. As a result, the unit production cost of the Australian wine industry, while having fallen in USD and GBP, has not declined relative to its major competition.

A Porter Analysis highlights the poor market position faced by wine producers given the concentration and high market power of customers (ie. retailers like Woolworths in Australia, Costco in the US, and the supermarket chains in the UK and Europe), and the fragmented competitor base.

As a result, at least some of the benefit of the falling AUD on export margins is likely to be competed away. TWE’s FY15 (2015 financial year) result showed this with the company’s average unit price in constant currency falling 0.6 per cent in EMEA and 2.2 per cent in the Americas relative to FY14.

Adding to this is the complexity in the supply chain for wine companies. One of the major changes in consumer products markets over the last 30 years has been a shortening of the supply chain. This has allowed companies to react more quickly to changes in consumer preferences.

Wine companies have very long dated supply chains. As such they are like a retailer that is required to purchase stock 3 to 5 years before selling it. This limits the ability to adapt quickly to changes in consumer preferences.

The long dated supply chain means that the planning for a product being sold today began 5 to 10 years ago, even for a A$5 bottle of wine. This is due to the duration of grape supply contracts (~3-5 years), a 1-2 year production and ageing process, harvesting and processing only occurring for 3 months a year (resulting in idle capital for the other 9 months), and a lack of product homogeneity.

This last point is very important. What this means is that due to an inability to blend wines across regions, varietals and vintages without devaluing the end product in most cases, inventory management is extremely difficult.

For example, let’s assume a company signs grape supply contracts based on its estimate for demand for sauvignon blanc from the Adelaide Hills using its current demand. However, over the next five years the consumer wakes up to the fact that sauvignon blanc tastes like sucking on a piece of fertilised grass and demand falls resulting in the original demand forecasts proving to be too high. Over a 5 to 7 year period, consumer preferences can change significantly. But the poor wine maker has already locked in what they will produce.

Unfortunately the wine company will have to accept more sauvignon blanc grapes than it needs from the growers because the contracts are generally take-or-pay. The options for the wine producer are limited. They could sell the grapes, but would generally incur a loss. They could produce the wine and hope to move it by discounting. They could try to blend it with other wines, but this is limited without making the wine more generic and lower value due to labelling laws.

Then think about multiplying this one example across every region and varietal the wine maker draws grapes from, and then again across multiple vintages and you can see that the supply chain complexity of a wine business is extremely challenging.

On top of this, the industry exhibits sunk cost economics due to around 45 per cent of the cost of a bottle of wine being grapes, which are paid for just after vintage, while the wine is not sold for 6 to 36 months after vintage. Lastly, the market value of bulk wine generally depreciates over time. So if the wine does not clear as expected, the combination of the amount of capital tied up in stocks starts to rise, and its value falls.

The industry structure and nature of the business add to the risk in assuming significant uplift in earnings and returns from the falling AUD. Consequently, there would need to be underlying improvement in the business to justify a positive investment case. We look at this in the next part of the series.

Stuart Jackson is a Senior Analyst with Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY