Quality and patience are key

Humans are hard-wired, it seems, with an affinity for narrative over data. When the equity market falls over the course of a day, for example, we want an explanation for what happened. Something vague and unprovable like “profit taking” will do nicely. This explanation offers no real insight into the market, or what it might do tomorrow, but it accounts for the behaviour in familiar and immediate terms, and any explanation is preferable to a shrug of the shoulders or a dry, statistical account of market variability. Not as honest perhaps, but certainly more comforting.

However, it is also true that investment markets can be a treasure trove of empirical data for those who would be guided by the evidence. While academic research papers might not have the “comfort food” appeal that a good narrative has, there is an abundance of genuinely insightful high-quality and freely-available research material that deals with investment markets. It can take some effort to work through this sort of material, and that is not everyone’s cup of tea. However, for those who crave something more concrete than a glib explanation of day-to-day price moves, this can be an excellent place to spend some time. Let me pour you a cup and see what you think.

One of my favourite research authors is Cliff Asness, a founder of AQR (Applied Quantitative Research). As the name suggests, AQR focuses on quantitative, research-based investing, and Cliff and his team produce some thoughtful research pieces which are freely shared on the AQR website.

One such piece of work is focused on something near to our hearts here at Montgomery – business quality. The paper: Asness, Frazzini and Pedersen (2014), “Quality Minus Junk”, can be downloaded here.

In this paper, Asness et al describe the differences in investment performance between high and low-quality businesses, using data for the US stretching back to the 1950s, (“Long Sample”) and for a selection of 24 different countries across a shorter timeframe (“Broad Sample”).

To cut straight to the chase, Asness et al find that high-quality stocks have higher risk-adjusted returns than low-quality returns in 23 out of the 24 global markets they study (what’s with that, New Zealand?). This is a powerful conclusion, and given the thorough nature of the research, it’s a conclusion that investors might reasonably feel confident in. Being able to have confidence in the results is a critically important point, for reasons that I’ll come to in a moment.

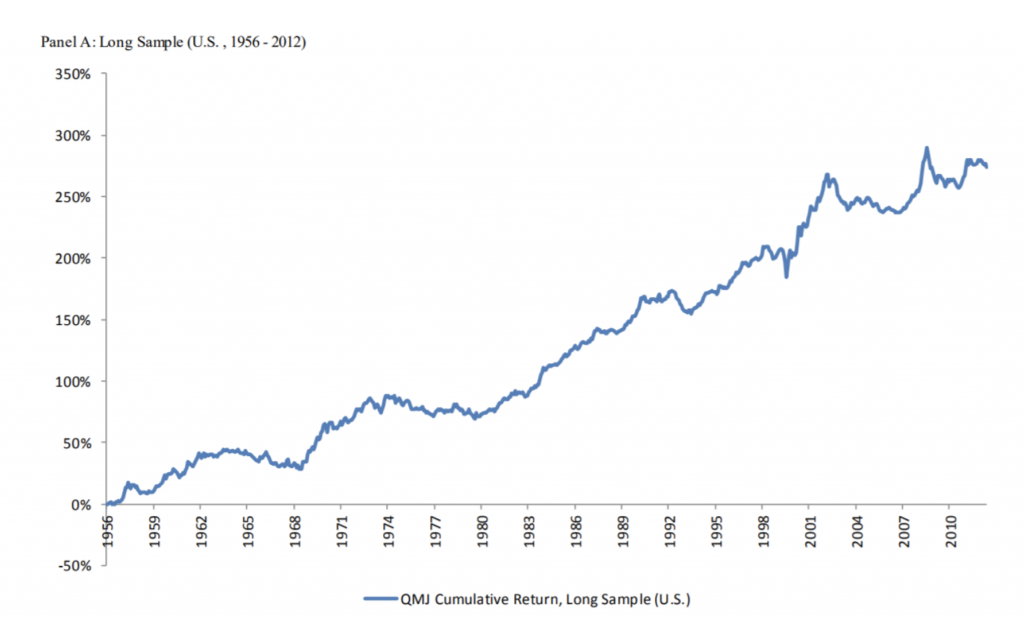

One of the numerous interesting charts in the paper is the one below, which sets out the cumulative return to a portfolio that buys high-quality stocks and short sells low-quality stocks, for the US market for the period from 1956 – 2012 (Long Sample).

For me, this chart makes some important points that can provide meaningful guidance to an investment strategy. These points include:

- Quality works. Owning the highest-quality businesses, and avoiding the lowest-quality businesses delivers better investment results.

- Quality doesn’t always work. Sometimes, the returns go backwards.

- Sometimes they go backwards for many years at a time, before ultimately recovering.

There is some good news and bad news in these conclusions for quality investors. The bad news is that quality can underperform for long stretches of time, with the period from 1974 to 1980 standing out as a painful example. In Australia, we have recently seen a period of marked underperformance, but the historical evidence shows that this is not unusual, and the underperformance could continue for some time yet.

The good news is that for patient investors, quality has repeatedly recovered from these periods of underperformance and ultimately delivered superior results. With many decades of evidence across a broad range of countries to consider, it seems reasonable to expect that quality will emerge from the recent weak spell and ultimately make new highs.

Finally, the research serves as a reminder of something we all know, but find difficult to put into practice: timeframe and patience are the hallmarks of good investment decision making.

Regardless of whether or not academic research is your cup of tea, you’ll do better if you don’t check the kettle too often.

Thanks Tim for that interesting article. I guess the big questions that remain are how you actually determine what constitutes a ‘high quality’ stock ( there are a wide variety of methodologies different analysts use), and whether what may be considered a high quality stock today will necessarily remain so tomorrow. The paper mentions a company that is growing as one criteria for a high quality stock, but this becomes a bit of a circular argument – it’s high quality because it’s earnings per share is growing which would already be reflected in the rising share price. Another criteria is that a company should be ‘well managed ‘- but how do you objectively measure that? There are still a lot of unknowns, subjectivity and forecasting uncertainty built into all of this and I guess that’s why we have a market of buyers and sellers.

That’s a good point, Fred. The research paper outlines a mechanical approach to determining quality; we prefer to rely on commercial judgment. Either way, it is possible to make an incorrect assessment, and “quality” can change as technology and business models change.

Hi Tim, thanks for the article. Just a thought on the chart – it indicates 3 times your money over a period of 50 years (unless I’m misreading the chart? quite possible!) – its not a great return!

Kelvin

That’s a fair point, Kelvin. 300% on the chart corresponds to 4x money, but still a modest outperformance of a couple of percent p.a. Tables elsewhere in the paper show a more granular view of performance by quality decile, and there is also a risk benefit to consider (higher quality names tend to be lower risk), but at the end of the day the opportunity is no more than a handful of percent p.a. of outperformance.

Thanks very much Tim.